Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks (USGNBs) are gradually becoming an important skill set for the emergency physician and will soon be an expected core competency for emergency medicine (EM) residents. Understanding the importance of a multimodal strategy for acute pain control has become an imperative during the current opioid crisis, as well as an ideal method to provide optimal pain control to patients. Similar to other procedures that emergency physicians have learned and adapted from our anesthesia colleagues (endotracheal intubation, central venous cannulation, etc.), USGNBs have been integrated into clinical practice at various emergency departments (EDs). Academic emergency physician groups have published research detailing reduced reliance on opioids as well as improvements in patient pain scores and functional outcomes when USGNBs are performed in the ED.1 A recent large multicenter study demonstrated decreased mortality when USGNBs are used for patients who present with acute hip fractures.2 Additionally, integrating USGNBs as part of a multimodal pathway for acute pain management may decrease or even prevent the development of chronic pain.3

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 01 – January 2023Some may argue that specialized academic EDs are the only place where USGNBs can be performed, but we believe the opposite. Smaller non-academic and/or non-trauma centers without specialty pain services are where many patients present with acute injuries; emergency physicians are often the only physicians available during off-hours with the procedural skills to perform USGNBs for optimal pain control. The development and integration of USGNBs into modern emergency care is imperative in reducing over-reliance on monomodal opioid-centered therapy and providing patients with optimal evidence-based care. We hope to describe a framework for EDs when developing an USGNB program that can be a part of a multimodal pain management pathway at various medical centers around the country (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: In order to build an UGNB program in your department, various aspects will need to taken into consideration (champion skill acquisition, education, collaboration and design).

USGNB Champion Skill Development

Integration of new techniques in emergency care always requires a clinician champion to develop domain knowledge. This was seen with the ED implementation of diagnostic point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), laryngoscopy, and more recently resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). These self-appointed clinician leaders have several methods available to obtain the skills and knowledge that are required to be champions for USGNBs in their respective EDs.

The first and often easiest method that fosters interdepartmental collaboration is to learn from trained regional anesthesiologists at your respective center. Especially in smaller hospital systems where non-siloed partnerships are common, learning essential blocks and needling skills in the operating room (OR) or post anesthesia care unit (PACU) can be an easy option for education. This also allows the ED champion to determine the equipment, medications, and tools already used in their hospital for USGNBs and to integrate them into ED practice.

An alternative method for USGNB skill acquisition is to take courses offered by various anesthesiology institutions (NYORA, ASRA, etc.). Regional and national EM conferences also offer such courses for novice clinicians that may be more tailored to the emergency physician. We recommend that the hands-on component (either in phantoms or cadavers) be a central aspect of the course, since proper needling technique is an essential skill.

Finally, the champion’s learning can be supplemented and refreshed at any time using numerous online resources and didactics. An online repository of USGNBs that are most useful for EPs, along with material and procedural considerations, can be found at highlandultrasound.com. Other high-yield free open access medical education (FOAMed) resources for USGNBs are Core Ultrasound (coreultrasound.com/), The Pocus Atlas (thepocusatlas.com/), NYSORA (nysora.com/) and Duke Regional videos (youtube.com/@regionalanesthesiology). Guidance is also easily referenced at the bedside on your smartphone via several highly regarded applications, such as the “Nerve Block,” “The POCUS Atlas,” or “NYSORA Nerve Blocks” applications.

Teaching

Once a USGNB champion has acquired the skills to perform blocks, they will need to establish a training pathway for other physicians at their institution. Scaling beyond the superuser is often the most challenging step. The champion should identify one or two high-yield USGNBs based on common injury patterns seen in their ED population. Many centers will likely find the femoral nerve block for hip fractures, the serratus anterior plane block for rib fractures, and forearm nerve blocks for hand injuries to be the easiest to teach and pertinent to their population’s needs. Limiting the number of USGNBs included in the initial training of novice staff will allow learners to focus on the general principles of regional anesthesia as well as good needling techniques. After proficiency is obtained with baseline principles, programs can choose to introduce further USGNBs via continuing educational training modules. We recommend a training pathway that incorporates both lecture-based and hands-on training. Trainers can leverage the large quantity of existing FOAMed resources already available, as referenced above.

Hands-on teaching is a crucial component of learning any procedural technique. Training should be tailored to the learner’s baseline level of experience with procedural ultrasound. Learners with minimal experience performing ultrasound-guided procedures or in-plane needle visualization technique may benefit from the use of needle trainer devices. These devices can either be purchased or created at home using household supplies (intelligentultrasound.com/needletrainer/, simulab.com/collections/regional-anesthesia-trainers).4 Programs can also use existing internal hospital simulation centers if available to provide this component of training.

Clinical hands-on training can be accomplished in the ED when learners are working alongside the USGNB champion. However, a busy ED shift can be suboptimal for teaching a new procedure, and learners can consider scheduling training shifts in the ED with the USGNB champion to perform blocks on acutely injured patients. The USGNB champion can also consider establishing agreements with the Anesthesia Department to allow learners to gain expertise from anesthesiologists performing USGNBs in the perioperative setting.

Collaboration

An USGNB program requires buy-in from multiple hospital departments. Anesthesia, orthopedics, surgery, and other services may not be aware of the benefits of USGNBs for acute pain in the ED. We recommend formal meetings with various stakeholders to develop a clear interdepartmental plan for optimal pain control in patients with acute injuries. Using previously published data that defines benefits of ultrasound-guided femoral nerve blocks for hip fractures, we recommend service lines (emergency medicine, anesthesia, and orthopedics) build a vertical protocol (from the ED to the OR) that relies on a patient-centric approach to pain management. A collaborative, multidisciplinary, non-siloed care pathway provides patients with optimal care and leverages our anesthesia colleagues’ knowledge to teach the ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block to their more novice emergency medicine colleagues. This patient-centered approach to pain management can translate to other injuries that will be managed in conjunction with other service lines (e.g., rib fractures for the trauma service).5,6,7

First demonstrating USGNB proficiency on non-admitted ED patients (palmar lacerations, metacarpal fractures, rib fractures, etc.) will generate respect and trust from consultants. Prior to expanding USGNBs to patients whose care is multidisciplinary, it is essential to communicate and collaborate with everyone who will be caring for the patient downstream (orthopedics, trauma surgery, anesthesiology). Common concerns include documentation, masking of the neurologic exam or compartment syndrome, and peripheral nerve injury. While the body of literature supports the benefits and safety of USGNBs in the ED, these risks are rare, but real.

Having to rely upon nursing to retrieve medications can introduce barriers and time delays to executing USGNBs in your department. Protocols with pharmacy colleagues can provide access to local anesthetics, adjuvants, and intralipid outside of the Pyxis (or other automated medication dispensing systems) which can drastically improve clinician workflow. In our department, EPs bring a “block box” containing all of these medications to the bedside, place a patient sticker on the included inventory sheet and mark what medications were used, then return the block box to the ED pharmacist or charge nurse.

Credentialing

In 2021, ACEP issued a policy statement specific to USGNBs, affirming that USGNBs performed by emergency physicians are not only within the scope of practice but a “core component” of pain control for ED patients, pointing to their rising role as the new standard of care for acutely ill or injured patients (acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/ultrasound-guided-nerve-blocks/). Landmark-based nerve blocks have long been a part of the American College of Graduate Medical Education’s EM residency education requirement. Ultrasound-guidance improves the safety profile of nerve blocks. According to ACEP guidelines the physician with emergency ultrasound privileges needs no outside certification to perform USGNBs (acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/emergency-ultrasound-certification-by-external-entities/). While this may seem surprising to some, note that no other clinical procedure requires special external certification, e.g., central venous access or intubation, which follow a similar historical path of being brought into EM after initially exclusively being performed by anesthesia or critical care specialists. As with EM, anesthesia physicians also require no additional certification to perform nerve blocks.8

Initiating and updating emergency physicians’ USGNB privileges can be safely done via intradepartmental credentialing approval process. ACEP guidelines require individuals obtaining initial credentialing complete the training and proof of competency determined by their own emergency department.9 In departments with established emergency ultrasound programs (i.e., an ultrasound division or an ultrasound fellowship) newly branching into USGNBs, the ultrasound director should partner with the USGNB champion to create an appropriate process for credentialing of individuals.10 In EDs without a distinct ultrasound division, the USGNB champion should partner with the EM chairperson to determine what training and proof of competency would be appropriate.

At this time, the exact number of supervised nerve blocks an ED provider needs to perform to be independently capable is unclear. ACEP guidelines suggest an approximate threshold of 10 when new ultrasound procedures which build upon existing procedural skills, e.g., 10 transvaginal ultrasounds for those who already perform POCUS, rather than the usual threshold of 25 when learning a new application of ultrasound. The principles of needle visualization required to safely perform ultrasound-guided vascular access, along with identification of neurovascular bundles and their relationship to surrounding muscle and other structure, are similar skills needed for USGNBs. This suggests that 10 total USGNBs may be an appropriate minimum threshold. However, given the broader range of USGNBs than typical vascular access sites, some departments may select a higher minimum for credentialing each provider. For reference, anesthesiology residency requires 40 nerve blocks across three years, recognizing that the spectrum of blocks performed by anesthesiology providers is likely much broader than those carried out in the emergency department. The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine recommends anesthesiologists perform 20 USGNB per year to maintain competence. As modeled in ACEP’s ultrasound guidelines, we feel it is best to leave it to each ED to determine their own credentialing threshold (aium.org/officialStatements/60).9

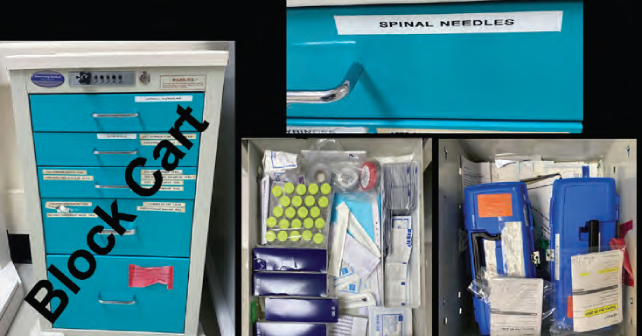

FIGURE 2: Our block cart allows clinicians

to perform UGNBs without looking for

various components. (Click to enlarge.)

Design

Block Cart: A user-based design approach will reduce barriers needed to perform USGNBs. Keeping all supplies needed for performing an USGNB in one location (either in a tray, bag or in a cart) will make the process of performing USGNBs easier. A block cart should be mobile, well organized, and routinely restocked to ensure its functionality. It should contains all of the equipment needed to perform USGNBs (skin preps, protective adhesive barriers, needles/block needles, syringes, sterile gel, marking pens), in addition to a diverse array of local anesthetics, adjuncts, and stocking of intralipid in case of rare but life-threatening complications (see Figure 2).

Documentation/Templates: Documentation of your USGNB is required for communication to other providers/services as well as for accurate and consistent billing. Clear templated notes in the electronic medical record will allow the clinician to document important information (indication for the block, block type, laterality, anesthetic amount used, complications, time the block was performed etc.). This information allows clear communication to colleagues who may see the patient during the inpatient stay or on a subsequent ED visit (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: Our UGNB template has

been built for the ED clinician. Documentation allows for proper data transfer to other clinicians

as well as billing.

Conclusion

USGNBs are becoming more common in the practice of emergency medicine. Along with being an excellent part of a multimodal pain regimen in an acutely injured ED patient, USGNBs may be an ideal alternative to time consuming procedural sedation. Like various procedural skills that have been adopted from other specialties (e.g., laryngoscopy, transesophageal echocardiogram, etc.), there are multiple challenges to integrating USGBNs into clinical care. We recommend that each department find a clinical USGNB champion who can acquire procedural skills as well as teach their EM colleagues a few commonly needed blocks. Also, working in collaboration with other hospital service lines will allow you to build patient centered protocols that address timely pain control. Finally, leveraging user based design principles by having all supplies required for USGNBs in one mobile location will reduce barriers to performing blocks.

Dr. Nagdev is emergency ultrasound director at Highland Hospital/Alameda Health System.

Dr. Howell is ultrasound fellow at Highland Hospital/Alameda Health System.

Dr. Desai is ultrasound fellow at Highland Hospital/Alameda Health System.

Dr. Martin is medical student/resident director at Highland Hospital/Alameda Health System.

Dr. Mantuani is emergency ultrasound fellowship director at Highland Hospital/Alameda Health System.

References

- Morrison RS, Dickman E, Hwang U, et al. Regional nerve blocks improve pain and functional outcomes in hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2433–2439.

- Lin DY, Woodman R, Oberai T, et al. Association of anesthesia and analgesia with long-term mortality after hip fracture surgery: an analysis of the Australian and New Zealand hip fracture registry. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2023;48(1):14–21.

- Levene JL, Weinstein EJ, Cohen MS, et al. Local anesthetics and regional anesthesia versus conventional analgesia for preventing persistent postoperative pain in adults and children: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis update. J Clin Anesth. 2019;55:116–127.

- N R, Gibson KI. A home-made phantom for learning ultrasound-guided invasive techniques. Australas Radiol. 1995;39(4):356–357.

- Schultz C, Yang E, Mantuani D, Miraflor E, Victorino G, Nagdev A. Single injection, ultrasound-guided planar nerve blocks: An essential skill for any clinician caring for patients with rib fractures. Trauma Case Rep. 2022;41:100680.

- Wroe P, O’Shea R, Johnson B, Hoffman R, Nagdev A. Ultrasound-guided forearm nerve blocks for hand blast injuries: case series and multidisciplinary protocol. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(9):1895–1897.

- Johnson B, Herring A, Shah S, Krosin M, Mantuani D, Nagdev A. Door-to-block time: prioritizing acute pain management for femoral fractures in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):801–803.

- Herring AA. Bringing ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia to emergency medicine. AEM Educ Train. 2017;1(2):165-168. doi:10.1002/aet2.10027

- Ultrasound guidelines: emergency, point-of-care and clinical ultrasound guidelines in medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(5):e27–e54.

- Amini R, Kartchner JZ, Nagdev A, Adhikari S. ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in emergency medicine practice. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(4):731–736.

No Responses to “How To Build an Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Block Program”