The Case

A 32-year-old female with facial injuries is brought to the emergency department by her sister. She states that she was walking her dog and fell forward onto the pavement when the dog pulled on the leash. She denies injuries other than those to her face (see Figure 1). She is uncertain whether she lost consciousness and complains of a headache.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 08 – August 2018Introduction

In the United States, more than one in three women and nearly one in three men have experienced sexual violence, stalking, or physical violence by an intimate partner.1 Among female victims of homicide committed by an intimate partner, nearly half had been emergency department patients within the two years prior to their deaths.2 The majority of victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) were emergency department patients multiple times without being identified as victims of IPV, even when injury was the presenting complaint.3 Clearly, emergency department staff have a unique opportunity to identify victims of IPV and to provide safety planning and community referrals.

Figure 1: Injuries to the patient’s face.

Photos: Brandi Castro, RN, SANE-A, SANE-P

Multiple organizations, including ACEP and The Joint Commission, recommend universal screening for IPV.4 Studies suggest that universal screening results in higher rates of identification of IPV.5 However, in reality, screening is far from universal. In one study of 433 women presenting to emergency departments, only 13 percent either volunteered information about IPV or were screened for IPV.6 A larger study of 4,641 adult women presenting to emergency departments suggested that patients want emergency department staff to ask about IPV, but fewer than 25 percent were screened.7

Emergency department staff cite several barriers to screening.8 The physical layout of many emergency departments makes it difficult to screen patients privately. Language barriers and time constraints may impede screening as well. Many emergency department staff have preconceived notions of what a victim of IPV should look like and do not screen patients who do not fit that profile. Given the prevalence of IPV, many of those responsible for screening have a personal or family history of IPV, which may make screening difficult. Other providers do not screen because they do not know what questions to ask or they are not familiar with community resources.

Screening

The ED staff responsible for screening for IPV varies among emergency departments. Often, the IPV screen is included in the initial triage assessment. Many departments have found that triage screening is impractical due to lack of privacy and critical medical conditions requiring immediate stabilization. If this is the case, the patient’s primary nurse or physician should screen as soon as practical. Clinical decision support in the electronic medical record may help prompt screening. For screening to be performed routinely, it must be built into the standard workflow.

Multiple methods of IPV screening have been studied in the emergency department, including direct questioning, written surveys, and computer-based surveys. Rates of identification are higher with self-administered surveys, whether paper-based or computer-based, than with direct questioning.9 Regardless of the method of screening, it is important to screen in a private location without visitors, including children over the age of two. Use nonjudgmental language, such as, “Because I see so much violence in my practice, I ask everyone these questions.”

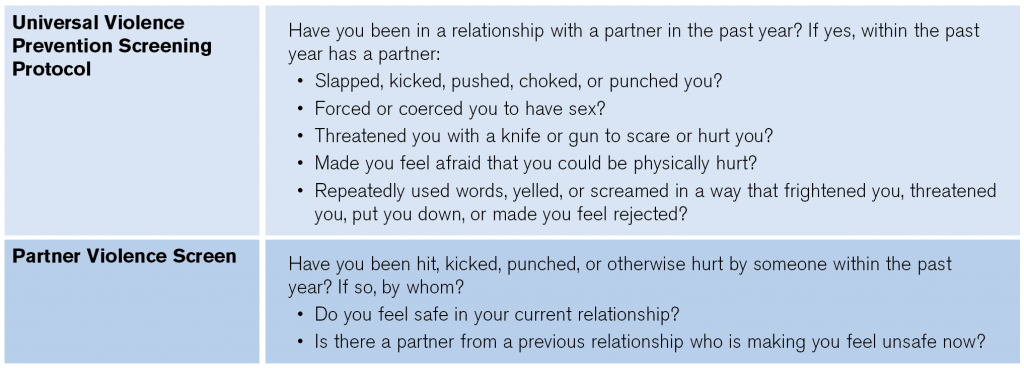

There are several validated IPV screens that may be modified to fit a particular patient’s situation.10 Table 1 has a list of common screening questions.

(click for larger image) Table 1: Common IPV Screening Questions

Source: Rozzi HV, Smale LE. Uncivil union: intimate partner violence. Crit Decis Emerg Med. 2018;32(3):3-9.

Disclosure

If patients disclose that they are a victim of IPV, provide an empathetic response such as, “I’m sorry that happened to you. How can I help?”

For many reasons, not all patients who disclose IPV are able to leave their abusive situations. Many victims of abuse stay for financial reasons. Others fear for themselves, their families, and their pets if they were to leave. Victims are the experts on their own safety, and it is the responsibility of the emergency physician to provide patients with resources and referrals tailored to the individual situation.

In some states, emergency physicians are mandated to report IPV to law enforcement. Emergency physicians should become familiar with the statutes in the jurisdictions in which they practice, and should inform patients of what they are legally required to report so that patients can make informed decisions about what to share with their physician.

Safety Planning

If the screen is positive, the patient requires a safety plan prior to discharge. It is important to know what resources are available in your area for victims of IPV. Depending on your hospital’s policy, social work, forensic nurses, or community IPV organizations may be able to assist with safety planning. Ideally, the IPV advocate should meet with the patient in the emergency department. If the patient declines assistance from the IPV advocate, contact information for community resources should be provided. Many IPV victims store this information in their phones under a fictitious name, as abusers may look at their victim’s contact list.

Case Conclusion

You note the circular injury on the patient’s right cheek (see Figure 1), which appears to be consistent with a bite wound. She also has injuries to the neck (see Figure 2) that are inconsistent with the history provided. When the patient goes to radiology for imaging, her sister is asked to remain in the emergency department. Before the radiology tech comes into the room, you ask the patient, “Many times, injuries like this are caused by another person. Did someone hurt you?” The patient begins to cry as she reveals that her husband punched her repeatedly. She lost consciousness and did not recall what happened after that. She begs that her sister not be told, but she is willing to speak privately with the hospital social worker. Once finished in the emergency department, she plans to take her dog and stay at a friend’s home.

References

- Smith SG, Chen J, Basile KC, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010-2012 State Report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2017.

- Wadman MC, Muelleman RL. Domestic violence homicides: ED use before victimization. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(7):689-691.

- Kothari CL, Rhodes KV. Missed opportunities: emergency department visits by police-identified victims of intimate partner violence. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(2):190-199.

- Policy statement: domestic family violence. ACEP website. Available at: https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/domestic-family-violence/#sm.0000jtp3b8vvbdobu5z1bbgrrl321. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- Ahmad I, Ali PA, Rehman S, et al. Intimate partner violence screening in emergency department: a rapid review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(21-22):3271-3285.

- Abbott J, Johnson R, Koziol-McLain J, et al. Domestic violence against women. Incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA. 1995;273(22):1763-1767.

- Glass N, Dearwater S, Campbell J. Intimate partner violence screening and intervention: data from eleven Pennsylvania and California community hospital emergency departments. J Emerg Nurs. 2001;27(2):141-149.

- Gremillion DH, Kanof EP. Overcoming barriers to physician involvement in identifying and referring victims of domestic violence. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(6):769-773.

- Trautman DE, McCarthy ML, Miller N, et al. Intimate partner violence and emergency department screening: computerized screening versus usual care. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(4):526-534.

- Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2007.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “How to Help Victims of Intimate-Partner Violence”