Running an effective and evidence-based cardiac arrest resuscitation is a core skill for all emergency physicians. To identify reversible causes of pulseless electrical activity (PEA), emergency physicians have integrated point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) into care for this group of critically ill patients. Specifically, during the brief 10-second pause of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), the goal is to rapidly assess for signs of cardiac tamponade, massive pulmonary embolism or other reversible causes of arrest. Unfortunately, two emergency medicine studies have demonstrated that emergency department POCUS use during the resuscitation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests may inadvertently prolong CPR pauses, which has been shown to negatively impact survival.1,2 Multiple regression analysis demonstrated that POCUS was associated with longer pauses (6.4 s, 95%CI 2.1- 10).8 We believe that with some minor adjustments, we can effectively and safely incorporate POCUS into cardiac arrest resuscitation. Additionally, a recent novel concept from the resuscitation literature allows the clinician to take advantage of the benefits of imaging, while ensuring high-quality uninterrupted CPR.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 09 – September 2023Simple Steps to Improve Quality CPR When Using POCUS

The resuscitation of the patient in cardiac arrest can be difficult for even the most seasoned clinician. Protocolization of POCUS can offer a reduction in cognitive burden during this demanding period. Data at our institution and another large academic emergency department indicated that physicians were inadvertently increasing the duration of CPR pauses when using POCUS, forcing us to develop a simplified clinical POCUS pathway. ACEP Now’s three-step cardiac arrest sonographic assessment (CASA) protocol asked the clinician to rapidly (in under 10 sec) answer one question during each CPR pause.3

Look for a pericardial effusion on the first pause, right ventricular (RV) strain on the second pause, and cardiac activity on the third pause. Each step was meant to streamline the CPR pause duration, while also allowing the clinician to determine the need to act on a reversible cause of the cardiac arrest. During active compressions, the clinician could also examine the thoracic cavity for the presence of a large pneumothorax, and the abdomen for the presence of intra-abdominal fluid.

As expected, integration of this simplified protocol over the past five years has resulted in a decrease in CPR pause duration at our institution. We also have implemented simple adjuncts (in addition to the CASA protocol) to ensure high-quality CPR.

- Find the echo view before pause: During CPR, the clinician who is performing POCUS should attempt to find the ideal view of the heart. Often, this is a subxiphoid view, but can also be a parasternal long or apical four-chamber view (see Figure 1). The goal is to have a reasonable view before the CPR pause so that time is not wasted finding an adequate window.4

FIGURE 1: A) Subxiphoid view demonstrating a pericardial effusion with signs of echocardiographic tamponade B) Apical four-chamber (A4C) view demonstrating right ventricular strain in a patient with a massive pulmonary embolism C) Three views of the heart when attempting to find a good window to image during cardiac compressions. (Click to enlarge.)

- Use a 10-second clock: Our nurse recorder for the code counts out loud from 10 to one during the pause so that the scanning clinician knows when to get off the chest. Chest compressions are always started at the end of the 10 seconds unless return of spontaneous circulation(ROSC) or a shockable rhythm is recognized. Also, we have set our recording timer on our ultrasound systems to six seconds so that the clinician is aware of the duration of the recording.

- Review clip during CPR: The clinician records the ultrasound clip during the pause and then interprets the video after CPR restarts.

- Stay off the chest after showing there is no pericardial effusion or signs of right ventricle (RV) strain: Each time the probe is placed on the chest for evaluation of cardiac activity, the physician risks a prolonged pause. Once POCUS has ruled out potential reversible causes of cardiac arrest (tamponade or RV strain), avoid excessive, repeat, cardiac ultrasound evaluations during CPR pauses. The goal at this point is to identify ROSC.

Modification to the CASA Protocol

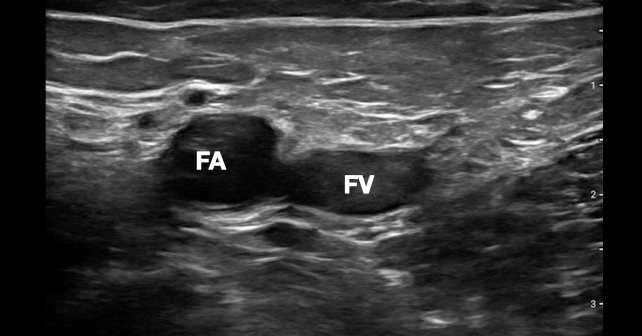

After the first two steps of the CASA exam are negative (there is no clinically significant pericardial effusion or RV strain), our standard technique was to identify the presence of cardiac activity (at each subsequent pause), as a surrogate marker for ROSC. Unfortunately, there is significant variability between physicians when assessing for the presence of cardiac activity.5 Additionally, there is uncertainty as to what degree of cardiac activity generates sufficient perfusion to safely stop CPR. From our clinical experience, there have been many instances when slight but concentric cardiac activity is noted on POCUS without a palpable pulse, making it unclear if CPR should continue. Recent data using ultrasound evaluation of the femoral artery have helped change the way we employ ultrasound in cardiac resuscitation. Instead of using our phased array transducer to assess for the presence or absence of cardiac activity (with the worry of prolonging CPR pause time and misinterpreting the presence of enough cardiac activity to produce a perfusable blood pressure),we have moved to the femoral region for imaging during CPR pauses. We switch to a linear probe, and image the femoral artery using B-mode as a surrogate for ROSC.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “How To Safely Incorporate Ultrasound Into Cardiac Arrest Resuscitation”