Injuries to the upper extremity (e.g., fractures, dislocations, lacerations, abscesses, and foreign bodies) are common, but can be challenging to manage in the emergency department (ED) due to severe pain.1 Procedural sedation and/or hematoma blocks can be great tools for pain control but, in our experience, often fail to provide adequate analgesia. While the use of hematoma blocks for lower forearm injuries such as distal radius fractures have been shown to be effective, there is little evidence suggesting that they are effective in upper arm injuries.2-4 Also, procedural sedation requires significant resources (e.g., additional nursing staff, a respiratory therapist, and monitoring equipment).5-7

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 04 – April 2023Single-injection, ultrasound-guided, brachial plexus blocks provide targeted analgesia for upper extremity injuries. Specifically, the interscalene block is effective for proximal injuries including the deltoid and shoulder and the supraclavicular block may be ideal for injuries at the elbow or lower.8 The supraclavicular brachial plexus block has a number of advantages including visualization of the brachial plexus, clearly defined ultrasonographic landmarks, and having been used for various arm injuries (from distal humeral injuries to distal radius fractures) in our ED. By delivering sonographically guided anesthesia, we can effectively reduce pain, opioid utilization, and need for procedural sedation.

The following sections outline important clinical anatomy, equipment for the block, and procedural steps that will allow for a successful supraclavicular brachial plexus block.

Indications and Considerations

The supraclavicular brachial plexus block is indicated for anesthesia and analgesia to common ED injuries below the shoulder including but not limited to: deltoid abscess, midshaft and distal humerus fractures, and elbow dislocations. For simplicity we think of the interscalene brachial plexus block for injuries from the proximal shoulder to the distal humerus and the supraclavicular brachial plexus block for injuries beyond the distal humerus.8 The decision to perform a brachial plexus block is a multifactorial decision. The clinician should be aware of the patient’s underlying medical history as well as have clear communication with the other services who may need to be involved in the patient’s care. Also, in our experience, sonoanatomy of the brachial plexus can be varied (both in location and overlying vasculature). Finding the right location (whether supraclavicular or interscalene) or not performing the block will depend on the patient’s underlying sonoanatomy as well as the ability to position an acutely injured patient.

Allergies, overlying infections, and coagulopathy are important contraindications, as with all peripheral nerve blocks.9 There are a few important limitations to the supraclavicular brachial plexus block that should be considered:

- Injuries to the to the medial upper arm are not covered by brachial plexus blocks.

- Interscalene blocks often provide better analgesia for shoulder dislocations.

- For injuries to the hand (distal to the wrist crease), a forearm nerve block may be more appropriate.

Anatomy

The brachial plexus is composed of nerves from the C5 to T1 nerve roots that travel from the cervical spine and innervate the neck, axilla, and arm. The brachial plexus branches as it travels from the cervical spine to the upper extremity, and the location of a block should be tailored to cover the nerve distribution of the injured region.

When performed correctly, the supraclavicular nerve block will provide motor and sensory blockade to the radial, median, ulnar, musculocutaneous, and axillary nerve distributions of the arm. This leads to almost complete anesthetization of the arm, sparing the shoulder joint (suprascapular nerve) and the medial side of the upper arm (intercostobrachial nerves).

Equipment

Overall, the supraclavicular brachial plexus block requires similar equipment as other ultrasound guided nerve blocks:

- An ultrasound system with high-frequency 15-6 MHz or 10-5 MHz linear transducer set at the nerve (or soft tissue)

- A block needle: Preferably a 20- or 21-gauge, blunt-tipped, regional-block needle

- Appropriately sized syringe to draw local anesthetic

- Sterile saline flushes for hydrodissection

- Transparent adhesive ultrasound probe cover (Tegaderm, etc.)

- Antiseptic (e.g., alcohol, povidone/iodine, chlorhexidine)

- Sterile ultrasound gel

Procedure

Set-up

Place the patient on a cardiac monitor and ensure stable intravenous access. Position the patient supine in a 45-degree semi-upright position. Position the ultrasound system across from the affected extremity so that the patient’s exposed neck and the ultrasound screen are in the same line of sight. We recommend placing either a pillow or roll of blankets beneath the ipsilateral shoulder to improve block ergonomics (Figure 1A: picture of screen contralateral plus pillows to roll the patient). Set the ultrasound system to the “nerve” preset and cover the linear (high frequency) transducer with a transparent adherent dressing. We recommend using sterile surgical lubricant as a coupling agent if possible.

Also, always perform and document a neurovascular examination prior to performing your block.

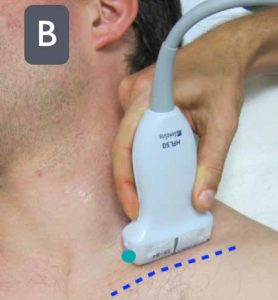

FIGURE 1B: Place the ultrasound probe (green dot indicating

probe marker) above the clavicle aiming the beam into the thorax. (Click to enlarge.)

Sonoanatomy

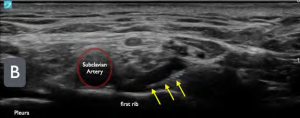

Place the high-frequency linear transducer above the upper border of the mid-to-lateral clavicle in a coronal oblique plane (parallel to the clavicle and aiming the beam into the thorax) (Figure 1B). Move the transducer medially to find the anechoic, round, and pulsatile subclavian artery (can be confirmed by color Doppler). The brachial plexus often appears superior and lateral to the artery, and often looks like a “cluster of grapes.” Note the first rib, a hyperechoic line with distal shadowing just under the brachial plexus. This should be contrasted to the normal lung sliding in the far field (Figure 2). In many patients, the first rib may not be clearly seen and the clinician will have to rotate the tail of the transducer in a counterclockwise manner to bring this sonographic landmark into view (Figure 3).

An alternative technique, should you have difficulty finding the brachial plexus, is to start in the neck by identifying the carotid artery and internal jugular vein about the level of the cricoid cartilage.8 Slide the probe inferiorly toward the clavicle, reducing the angle between the probe and the skin as the probe is moved. In addition to using the subclavian vessels as a landmark, also be sure to identify any other vascular structures in the area of interest. After locating the brachial plexus and the projected needle path, we recommend use of color Doppler to prevent inadvertent vascular puncture.10

Performing the Block

Once the optimal transducer position and needle path is identified, place a small skin wheal of local anesthetic just lateral to the transducer to anesthetize the overlying skin. After properly disinfecting the skin, enter through the skin wheal for a lateral to medial in-plane approach with the nerve block needle. Ensure continuous needle visualization and advance the needle tip until it touches the first rib. The goal is to find the area between the first rib and nerve bundle to inject anesthetic. Once you have clear needle-tip visualization within this space and have gently aspirated to ensure the needle tip is not intravascular, we recommend gently injecting a small amount of normal saline to ensure proper spread of anechoic fluid (hydrodissection).

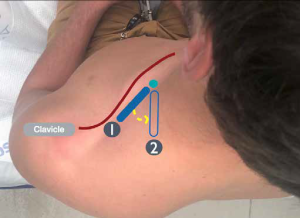

FIGURE 3: By rotating the ultrasound probe in a counterclockwise manner, the first rib can often be seen more clearly in cross-section on ultrasound. (Click to enlarge.)

The clinician should clearly visualize the fluid deposition on the ultrasound screen, and use this fluid to lift the nerve bundle away from the first rib (Figure 4). The clinician should then deposit small aliquots (3 to 5 cc max) every 15 to 30 seconds until the predetermined total anesthetic is deposited. If the needle location is adequate, a single injection should suffice, but repositioning the needle superiorly may be necessary to surround the nerve sheath completely with anesthetic. Once your injection is complete, gently remove the needle and dress the injection site as needed.

Aftercare

Mark the affected extremity with the date, time, and type of block performed. Document the block in the electronic health record. Communicate with nurse(s), other providers, and any relevant consultants that a block was performed. Reassess the patient to ensure adequate analgesia and assess the efficacy of the block. Also, reassess and document a repeat neurovascular examination.

FIGURE 4A: Schematic representation of a block needle entering lateral to medial in-plane and depositing anesthetic between the brachial plexus and first rib. (Click to enlarge.)

Conclusion

For upper extremity injuries, traditionally procedural sedation, local anesthesia, and hematoma blocks have been used for pain management during procedures in the ED. However, these strategies have their own disadvantages such as increased resource allocation for procedural sedation and possibly incomplete analgesia for hematoma blocks depending on the location. Brachial plexus blocks such as the supraclavicular block provide adequate analgesia for a larger variety of upper arm injuries when compared to the hematoma block and require fewer resources when compared to procedural sedation. This nerve block is safe, easily learned, and does not require advanced ultrasound training to perform.11

FIGURE 4B: Ultrasound image of a supraclavicular brachial plexus block. (yellow arrows = block needle). Note the anechoic (black) fluid between the first rib and the brachial plexus. (Click to enlarge.)

With an increase in the number of patients boarding in the ED, potentially decreased availability of procedural sedation rooms, and increasing patient-to-nurse ratios, ED physicians must adapt and become more efficient with limited resources. The supraclavicular block will not solve these systemic issues, but rather provides a more efficient strategy to manage pain better from acute upper extremity injuries as well as an alternative to procedural sedation in the ED.

Dr. Ayala is an emergency medicine resident at Highland General Hospital, Alameda Health System in Oakland, California.

Dr. Ashworth is an emergency medicine resident at Highland General Hospital, Alameda Health System in Oakland, California.

Dr. Nagdev is director of emergency ultrasound at Highland General Hospital, Alameda Health System in Oakland, California.

References

- Ootes D, Lambers KT, Ring DC. The epidemiology of upper extremity injuries presenting to the emergency department in the United States. Hand (NY). 2012;7(1):18-22.

- Tseng PT, Leu TH, Chen YW, Chen YP. Hematoma block or procedural sedation and analgesia, which is the most effective method of anesthesia in reduction of displaced distal radius fracture? J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):62.

- Lovallo E, Mantuani D, Nagdev A. Novel use of ultrasound in the ED: ultrasound-guided hematoma block of a proximal humeral fracture. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(1):130.e1-2.

- Bear DM, Friel NA, Lupo CL, Pitetti R, Ward WT. Hematoma block versus sedation for the reduction of distal radius fractures in children. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(1):57-61.

- Astacio E, Echegaray G, Rivera L, et al. Local hematoma block as postoperative analgesia in pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2020;2(3):155-158.

- Bellolio MF, Gilani WI, Barrionuevo P, et al. Incidence of adverse events in adults undergoing procedural sedation in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(2):119-34.

- Bhatt M, Johnson DW, Chan J, et al. Risk factors for adverse events in emergency department procedural sedation for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10):957-964.

- Nagdev A, Becherer-Bailey G, Farrow R, Mantuani D. How to perform ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve blocks. ACEP Now. 2020;39(4):21-22.

- D’Souza RS, Johnson RL. Supraclavicular block. In: StatPearls [Internet].(Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519056/. Updated July 25, 2022. Accessed March 11, 2023.

- Hahn C, Nagdev A. Color Doppler ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block to prevent vascular injection. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(6):703-5.

- Beals T, Odashima K, Haines LE, Likourezos A, Drapkin J, Dickman E. Interscalene brachial plexus nerve block in the emergency department: an effective and practice-changing workshop. Ultrasound J. 2019;11(1):15.

No Responses to “How To: The Ultrasound-Guided Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block”