Any time artificial intelligence (AI) is mentioned to doctors, it elicits a mixture of reactions that include discomfort, disgust, and distrust—sometimes all at once. Because my reaction when AI is mentioned in any health care context is engaged, hopeful, and possibly even giddy, I was unprepared these sentiments when I began my career in emergency medicine.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 01 – January 2021Even with a proper understanding, criticism of AI in health care reflects ongoing distrust. Distrust in medical research is not unique to AI. Furthermore, AI does not promise to be a silver bullet for many of our problems. But AI is a tool through which we can look at data already being collected and possibly garner more meaningful conclusions.

Even most experts agree that AI cannot predict anything that a human would not have been able to. So why is AI better?

The two primary advantages AI brings to medicine relate to reducing errors and improving financial sustainability by reducing inefficiencies.

Change is hard in medicine. That’s especially true when new technology is involved. I propose that AI in health care has the potential to be the singular most disruptive change we see in medicine over the next 20 years. If emergency physicians continue to ignore it, it will be a change that happens to us and to the detriment of our patients and our practice. Instead, we should embrace AI so the changes it brings are by us and for us.

AI in EM

Currently, more than 1,000 companies are integrating AI in various aspects of health care. Last year, more than $4 billion was invested by venture capital in this space. These numbers are expected to increase this year, reflecting the magnitude in anticipated future savings that may come from tackling widespread inefficiencies in the health care system. As we know, inefficiencies exist in almost every single link in the U.S. health care delivery chain.

Let’s explore some novel projects in five different categories that stand to have substantial impact on our practice of emergency medicine.

1. Information collection and processing: Smart devices are already collecting and interpreting information for patients, including everything from ECG bands for professional athletes to heart monitors on smart watches. There are “medical grade” smart devices such as pacemakers and Holter monitors that track heart rates, label what they see, and send alerts. By now, we have all seen or heard about patients seeking medical evaluation because of an alert they received or an anomaly they noticed from these devices. Now, it’s not just wearables that are making their way into hospitals. Aside from the telemetry monitoring devices, we will soon have other devices hooked up to our patients, analyzing (quite literally) their outputs. For example, Potrero has a bedside Foley device to automatically detect anomalies in urine output for early detection of acute kidney injury in ICU patients. It has been tested at Grady Hospital in Atlanta. With COVID-19 in our midst, the value proposition for remotely monitoring anything has skyrocketed. Think of all the personal protective equipment saved and the reduced risks to staff.

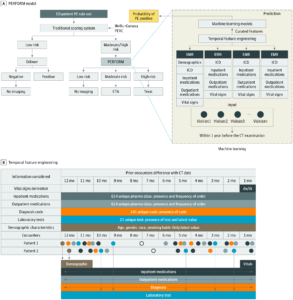

2. Medical decision making: Not everything in AI in health care comes from for-profit vendors. Researchers at Stanford University and Duke University completed a study on more than 3,000 patients, showing their AI algorithm’s ability to detect pulmonary embolism to be highly effective. It may even be the best existing algorithm from an accuracy perspective. Their model evaluated more than 750 different variables, including medications, demographics, vital signs, and all the data from an individual’s prior visits (see Figure 1). As a patient, which algorithm would you choose to decide whether you should get a CT angiogram? In this case, the accuracy was only about 80 percent. That’s still higher than other algorithms (about 70 percent), but some wiggle room remains. My prediction and hope: Can sepsis be next?

Overview of the Pulmonary Embolism (PE) Prediction Pipeline, Pulmonary Embolism Result Forecast Model (PERFORM) (Click image to enlarge)

CC-BY License. © Banerjee I, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e1987198.

Also included in this category are direct patient care algorithms. For example, CLEW is a platform that analyzes data from critically ill patients to give a dynamic work list for the optimization of patient outcomes over the following metrics: venous thromboembolism prevention, lung protective ventilation, stress ulcer prophylaxis, blood transfusions, and accelerated mechanical ventilation weaning and liberation.

3. Communication: Are you ready to hear about an AI start-up with technology that has already been approved for Medicare reimbursement? Viz.ai detects large vessel occlusion (LVO) on head CT/CTA. It is integrated into imaging software and sees the images as they are being collected. If an LVO is detected, it sends a message to all the current and future caregivers of the patient, from ED nursing to the neurointerventionalist who may perform a procedure. In other words, the downstream caregivers might automatically receive a text message about a patient before they have even seen them, depending on your center’s stroke workflow. Knowing this, are you surprised centers that adopt Viz.ai have seen a 50 percent increase in interventions?

Regarding the technology, in comparison with an experienced neuroradiologist, the Viz.ai algorithm performs with very high sensitivity (though mediocre specificity), with an overall accuracy of about 80 percent. This means it catches almost all the LVOs and then some. All of the cases are then presented to the neurointerventionalist directly. That said, some of the evidence that endovascular intervention for LVO is better than the best medical management for even mild stroke symptoms (NIH Stroke Scale ≤5) has been published by the same people who are evaluating the efficacy of the Viz.ai algorithm. Conflict of interest, anyone? The same people also argue that ASPECTS, a radiology scoring system to determine LVO from noncontrast head CTs, performs better than CT angiogram of the head and neck for determining presence of important and intervenable LVOs. Viz.ai evaluates both noncontrast CT and CT angiograms.

Enter Medicare. Viz.ai has Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for its technology, and in a milestone decision made in August 2020, Medicare now reimburses for it. Interestingly, the model for Medicare reimbursement only comes into play if your center is not currently benefiting from increased revenues coming from an increased number of performed interventions. Thus, it is basically a consolation prize to the community hospitals that are losing stroke admission–related revenue to the interventional centers that would have previously never accepted transfer of such patients (or treated them directly). Of course, clot retrieval is not without risks. Hopefully, an increase in these procedures will provide patients more benefits than harm.

Other start-ups in radiology and pathology are conducting clinical analyses on other imaging and specimen evaluations and their effect on medical decision making. As with strokes, though, the validation studies are often completed by researchers who either own stock or stand to reap financial benefits from AI technologies. Does this necessarily negate the effectiveness of the technology? No. Should we demand better standards of validation research? Absolutely.

4. Billing: While not part of direct patient care, the myriad applications of AI to medical billing that are ongoing right now should be discussed. In general, billing is the most underappreciated and underdiscussed determinator of our practice in emergency medicine. Changes in reimbursement patterns can alter our practices. Arguably, AI was first introduced in health care for reasons related to medical billing, and this makes sense since the revenue benefits are easy to measure and immediately realized and recognized. For example, natural language processing is used to scan through charts to find diagnoses we forgot to include, add procedures we forgot to document, and add missing information needed to justify the billing codes we used. AI is also used to better understand coverage denials and to identify strategic areas for potential fair increases in revenues.

In terms of billing for their own “services,” AI start-ups are seeing success in getting FDA approval. Medicare reimbursement is the natural next step. For example, Digital Diagnostics came out with a technology called IDx-DR that can detect retinopathies mostly caused by diabetes. Its technology is used internationally and for a low cost and has shown to be instrumental in early detection of diabetic retinopathy. Another example: Caption Health received FDA approval to deploy Caption Guidance, which is used for helping ultrasound operators capture high-quality cardiac ultrasound images. It was tested on previously untrained nurses. These caregivers were found to be able to capture high-quality images using this technology. Both of these technologies could be readily and legally adopted into our workflows. In fact, the only thing preventing widespread adoption probably is the economics (ie, billing). Given the reimbursement model described above, the floodgates of Medicare reimbursement for AI can be considered open now. It is only a matter of time before we begin to see how AI changes our diagnostic algorithms.

5. Process improvement: Imagine changes in staffing recommendations being made by an algorithm rather than management. The reality is that this is already happening and not just for physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. AI algorithms are being used to make recommendations on nurse staffing in the emergency department as well. Could this be a good thing and an answer to our understaffing problems? Yes! Unfortunately, right now, the opposite has been happening. To implement any technology, a cost-benefit analysis has to be done. If a staffing algorithm promises to save a system money, then one easy way to do this is by cutting hours, not increasing them. That said, research on predictive models for staffing emergency departments has been described in academic literature. There are even algorithms that take into account surges in patient volume.

Other areas of process optimization using AI include patient flow, protocol initiation, and really almost any computer-based task. A platform called Olive is designed as a health care bot, or a “digital employee.” It assists hospital employees across many departments including revenue cycle, supply chain, information technology, human resources, finance, accounting, pharmacy operations, and clinical operations. Olive provides a timely pop-up of what it “thinks” is useful information based on what it has learned about the user so far. One example is in patient information verification.

Conclusion

There are many steps that need to be taken so we physicians continue to have agency in our own practices. AI is not about ceding that; it’s about taking it back. We need to engage with researchers, vendors, administrators, insurers, and regulators so our voices as physicians can be heard. We need to advocate for our patients and our colleagues.

Ignoring AI is not the answer. We need to embrace AI and make it serve our needs. Decisions are being made with or without us. We all would prefer to be at the table that will shape the future of health care. Let’s do one better: Let’s be at the center of these conversations.

Dr. Garg is a practicing emergency physician at Lawrence and Memorial Hospital in New London, Connecticut. She also enjoys working on some healthtech projects on the side and is studying to be board certified in lifestyle medicine this year.

Dr. Garg is a practicing emergency physician at Lawrence and Memorial Hospital in New London, Connecticut. She also enjoys working on some healthtech projects on the side and is studying to be board certified in lifestyle medicine this year.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “If Physicians Embrace Artificial Intelligence, We Can Make It Work for Us”