Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 12 – December 2018Nothing is more concerning to parents and emergency health care providers than a serious illness that primarily impacts children. The concern is heightened when we don’t know the cause of the illness. These are the current circumstances for acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), and there is currently an ongoing seasonal outbreak of the disease in the United States.

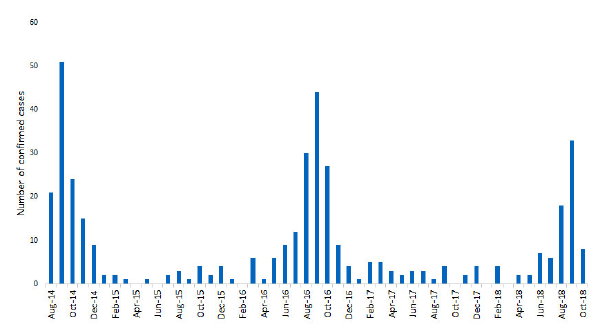

AFM is a rare condition that, similar to polio, destroys gray matter in the spinal cord, resulting in weakness that can progress to flaccid paralysis in hours. The condition first attracted attention in the United States in 2014 during a seasonal enterovirus outbreak.1-4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has raised concern because AFM cases have continued to show seasonal peaks each year since 2014 (see Figure 1), and we still don’t know the cause.5-7 In addition, AFM is being discussed in the news, generating increased awareness and apprehension. Clinicians are being encouraged to enhance their knowledge about AFM and rapidly engage departments of health for information on appropriate diagnostic and sampling methods for suspected cases.

The Background on AFM

Since it was first identified in 2014, there have been approximately 386 confirmed cases of AFM.5-7 The disorder is extremely rare, literally about one in a million. The mean age of patients is 4 years, with 90 percent of all cases occurring in patients younger than 18 years old. Despite research, we still don’t know the cause.5 Initially, all signs pointed to an enterovirus type D68, but that theory has not panned out.8,9 Continued investigations of possible sources including viruses, bacteria, and toxins, as well as inflammatory, autoimmune, and genetic disorders have all failed to clearly identify a culprit.

Prognosis

Little information exists regarding long-term prognosis of AFM. A general review of the existing reports suggests that out of 138 cases followed between 30 days to six months, 89.8 percent had persistent neurologic deficits, 8.7 percent were fully recovered, and 1.5 percent resulted in death.4,7,9,10

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

AFM should be suspected when patients (usually young) present with extremity weakness that is rapidly progressing. Early studies suggested up to 80 percent of patients reported an antecedent upper respiratory infection or enteritis.2,11 Another report noted that 75 percent of the cases had a low-grade fever a few days prior to onset of weakness.12,13 However, neither of these findings are consistent.1,4,7 Some patients present with an initial tingling and/or pain in the extremities. Urinary retention or a neurogenic bladder has been noted in some. Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation may develop rapidly. Additional presentations include facial palsy, ptosis, extraocular paresis, altered mental status, and bulbar findings such as slurred speech and dysphagia.10,13

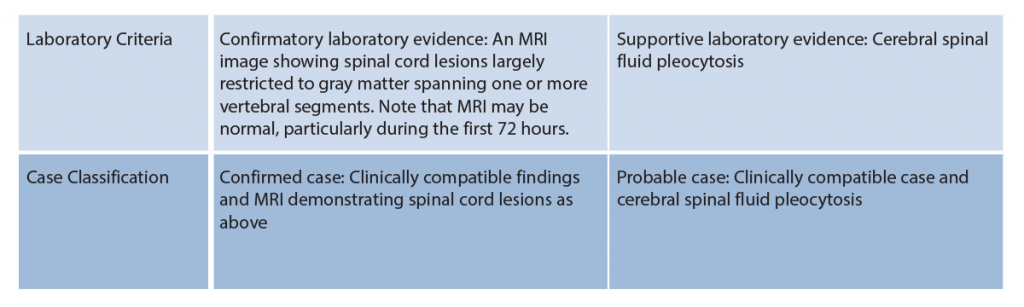

Laboratory studies are nonspecific. Analysis of cerebral spinal fluid often demonstrates a lymphocytic pleocytosis, normal glucose, normal or slightly elevated protein, and absence of identifiable viral, bacterial, or fungal pathogens.4,9,13

An MRI of the spinal cord is critical for diagnosis. The MRI may be normal on an initial presentation, but eventually an area of central gray matter lesions with edema of both the anterior and posterior segments of the spinal cord will develop. Lesions frequently occur over a span of several spinal cord levels and are most commonly located in the cervical spinal cord. Cortical lesions may also be noted.1,5,9 The classic appearance of the MRI has been described as similar to poliovirus infection.1,5

AFM can be difficult to diagnose, especially initially, because it shares many of the same signs and symptoms as other neurologic diseases, such as transverse myelitis and Guillain-Barré syndrome. The official elements for an AFM case definition, as defined by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, are provided in Table 1.14 However, clinicians are being asked to report all cases of weakness or paralysis meeting the clinical case presentation, regardless of MRI or laboratory results.5

(click for larger image) Table 1: Acute Flaccid Myelitis Case Definition

Source: Counsel of State and Territorial Epidemiologists

AFM Management

The onset of weakness may be abrupt and rapidly progress to respiratory failure. When these patients are evaluated in the emergency department or sent for MRI, the clinician should anticipate and be prepared for rapid deterioration. Hospital admission and appropriate consultation are indicated based on the condition of the patient and local institutional protocols. Patients with any indication of rapid progression or respiratory compromise should be admitted to the intensive care unit. The CDC expert panel on AFM discourages the use of steroids or other immunosuppressant agents as these may actually increase mortality.5 Further specific recommendations on AFM management may be found at the CDC’s AFM website, www.cdc.gov/acute-flaccid-myelitis.

AFM should be reported to the clinician’s state department of health and the CDC. These organizations can provide guidance on obtaining epidemiologic data and specimen collection to help identify the cause of AFM.5

References

- Pastula DM, Aliabadi N, Haynes AK, et al. Acute neurologic illness of unknown etiology in children—Colorado, August–September 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(40);901-902.

- Greninger AL, Naccache SN, Messacar K, et al. A novel outbreak enterovirus D68 strain associated with acute flaccid myelitis cases in the USA (2012-14): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(6):671-682.

- Ayscue P, Van Haren K, Sheriff H, et al. Acute flaccid paralysis with anterior myelitis–California, June 2012-June 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(40):903-906.

- Van Haren K, Ayscue P, Waubant E, et al. Acute flaccid myelitis of unknown etiology in California, 2012-2015. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2663-2671.

- Acute flaccid myelitis. CDC website. Accessed Nov. 19, 2018.

- Iverson SA, Ostdiek S, Prasai S, et al. Notes from the field: cluster of acute flaccid myelitis in five pediatric patients—Maricopa County, Arizona, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(28):758–760.

- Bonwitt J, Poel A, DeBolt C, et al. Acute flaccid myelitis among children—Washington, September–November 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(31):826-829.

- Aliabadi N, Messacar K, Pastula DM, et al. Enterovirus D68 infection in children with acute flaccid myelitis, Colorado, USA, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(8):1387-1394.

- Division of Viral Diseases, National Centers for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; Children‘s Hospital Colorado; et al. Notes from the field: acute flaccid myelitis among persons aged ≤21 years — United States, August 1–November 13, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;63(53);1243-1244.

- Martin JA, Messacar K, Yang ML, et al. Outcomes of Colorado children with acute flaccid myelitis at 1 year. Neurology. 2017;89(2):129-137.

- Sejvar JJ, Lopez AS, Cortese MM, et al. Acute flaccid myelitis in the United States, August-December 2014: results of nationwide surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):737-745

- Messacar K, Schreiner TL, Van Haren K, et al. Acute flaccid myelitis: a clinical review of US cases 2012-2015. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(3):326-338.

- Nelson GR, Bonkowsky JL, Doll E, et al. Recognition and management of acute flaccid myelitis in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;55:17-21.

- Revision to the standardized surveillance and case definition for acute flaccid myelitis. CDC Counsel of State and Territorial Epidemiologists website. Accessed Nov. 19, 2018.

Dr. Hogan is director of the TeamHealth National Academic Consortium and director of education for the TeamHealth West Group.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Important Information about the Seasonal Acute Flaccid Myelitis Outbreak”