Patients often present to the emergency department with multiple symptoms that do not fit clearly into one specific chief complaint or diagnostic pathway. In these atypical situations that defy simple description, policies and algorithms are difficult to apply. But when patients suffer unexpectedly bad outcomes, plaintiff’s lawyers are quick to point out any deviation from hospital protocols. This medical malpractice case highlights these issues.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 09 – September 2019The Case

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with several complaints. The triage note (see Figure 1) mentioned a sudden onset of feeling like his abdomen was “going to explode” and a vibrating sensation in his legs. Initial triage vitals showed a blood pressure of 169/84, pulse of 66 beats per minute, 18 respirations per minute, and a temperature of 96.1°F. The triage nurse listed the chief complaint as “chest pain” but later documented “pt denies chest pain.” His allergies listed an anaphylactic reaction to iodinated contrast.

Figure 1: Triage note

The physician’s note described the pain as starting suddenly while loading a car. He had an “abrupt onset of the sensation that he had a lid of a paint can that began in his epigastrium and slammed up into his jaw and then came down and continues to compress upon his abdomen.” The patient described feeling diaphoretic, a sense of his legs shaking, and a small amount of diarrhea. He denied chest pain to the physician. His past medical history was remarkable for history of aortic valve replacement, but he denied history of coronary artery disease or abdominal aortic aneurysm or other aortic syndrome.

The physician’s examination noted a “very kind and cooperative” patient. His large abdomen made the exam difficult, but an aortic pulsation was detected and noted to be “concerning given this gentleman’s proportions.” The vascular exam in his lower extremities was “symmetrically diminished.” The cardiac exam noted a systolic click.

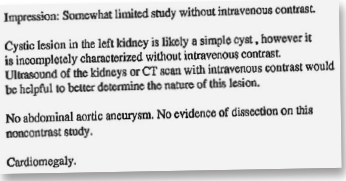

After taking a full history and exam, the physician documented a differential diagnosis that included a concern for abdominal aortic aneurysm, acute coronary syndrome, and renal colic. An ECG showed no acute signs of ischemia. An initial troponin level was negative. The patient medication list included warfarin, and his International Normalized Ratio was 2.8 in the emergency department. The complete blood count and metabolic panels were unremarkable. Given the history of anaphylaxis to contrast, a noncontrast CT scan of the patient’s abdomen was ordered. No abdominal aortic aneurysm or evidence of dissection was seen on CT (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Noncontrast CT scan results

These results were reviewed, and the emergency physician admitted the patient to the hospital. To ensure a telemetry bed for the patient, he entered the hospitalization order under “chest pain.” The hospitalist was contacted, interviewed and examined the patient in person, and admitted him. A cardiology consult was requested, and the cardiologist saw the patient several hours later on the floor. The cardiologist did not feel that this case was cardiac in nature but nonetheless recommended an ECG and a stress test for the following day.

When the hospitalist finished her shift, she signed out to the nurse practitioner (NP) covering the floor overnight. It was the NP’s first day at this job. During the sign-out, the hospitalist and NP received a call from the patient’s nurse that he had become hypotensive and looked unwell. They both immediately went to his bedside. A repeat ECG was ordered and was notable for borderline but suspicious ST-segment changes. Therefore, the hospitalist called the interventional cardiologist (a different cardiologist than who had initially completed the consult), and the patient was taken emergently to the cardiac catheter lab for what was presumed to be an acute coronary syndrome. In the cath lab, a large thoracic aortic aneurysm was discovered. Large hemopericardium was also found. The cardiologist believed that there was an area of fistulization from the aneurysm into the pericardium. An immediate consult with a cardiovascular surgeon was obtained, but the patient went into cardiac arrest shortly thereafter. Resuscitative measures were attempted, but unfortunately, the patient did not survive. The family did not request an autopsy.

The patient’s family subsequently contacted a law firm. After initial review, the family signed a contingency agreement agreeing to pay the law firm 40 percent of any settlement or verdict as well as all litigation expenses. The defendants included the emergency physician, hospitalist, first cardiologist, and hospital. The lawsuit was filed in federal court, as opposed to state courts (which handle most medical malpractice cases). This was done because the patient was from a separate state than the physicians and because the plaintiff’s allegations included an EMTALA violation.

Analysis

One of the primary issues that the plaintiff’s attorney used to support the negligence claim was the discrepancy in documentation about the patient’s chest pain. The triage nurse entered chest pain as the chief complaint, but the physician and nurse both wrote that the patient denied chest pain. The doctor hospitalized the patient on telemetry status due to chest pain, despite writing that he did not have chest pain. These contradictions provide easy fodder for the plaintiff’s attorneys to support their claims of negligence, regardless of whether intermittent chest pain changed initial management (the patient ostensibly received the initial workup that he would have had whether or not he had active chest pain at the time of evaluation).

This patient did not receive a chest X-ray despite the conflicting reports of chest pain. To worsen the matter for the defense, the hospital had a written policy for chest pain patients that allowed the ED nurses to order certain tests, including a chest X-ray. The plaintiff suggested that the emergency physician was negligent in his work-up, given that even a simple triage protocol called for an X-ray to be ordered. Additionally, the CT that was ordered in the emergency department was indeed an abdominal CT only and did not include the chest. Therefore, no thoracic imaging was obtained prior to admission.

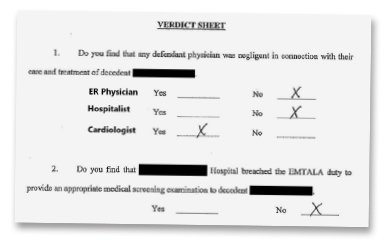

Both sides eventually agreed to enter into binding arbitration with a neutral party, with a cap on any settlement of $500,000. After reviewing the case, the arbitrator found that the emergency physician and hospitalist were not negligent and that there had been no EMTALA violation. The cardiologist who initially consulted on the patient was found to be negligent (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Arbitrator verdict sheet

The arbitrator awarded the plaintiffs $791,000 in damages, which was reduced to $500,000 per the previous agreement and was paid by the cardiologist’s malpractice insurer. As agreed, the law firm took 40 percent of the awarded damages ($200,000) plus their expenses of $69,000. This left $144,000 for the patient’s wife and $43,500 for each of his two children.

Take-home Points

There are several learning points from this case in regard to both medical care and documentation. A key concept is that fatal aortic pathology may not reliably localize to a specific anatomical area. If there is reasonable concern for aortic pathology, the entirety of the aorta should be imaged (a CT of the chest and abdomen/pelvis should be ordered for any aortic syndrome evaluation). (As a sidebar, it was later revealed that the patient’s reported anaphylactic reaction to contrast may not have been accurate, underscoring the importance of accurate medical record keeping in general.) Nonetheless, there are other options available for imaging the aorta, including MRI or transesophageal echocardiography. Emergency physicians should be prepared to advocate vigorously for the necessary testing, despite the fact that these are uncommon work-ups and may result in some pushback.

Finally, the documentation in this case presented problems for the emergency physician’s defense. Discrepancies between the physician and nurse created opportunities for criticism, even if management would not have been substantially altered by resolving that discrepancy in real time. More striking were discrepancies within the emergency physician’s own chart. This made it easy for the plaintiff’s attorney to suggest that a chest X-ray should have been ordered, potentially averting tragedy.

A review of the details of this case reveals a behind-the-scenes look at medical malpractice litigation, giving the reader practical tips to improve both their care and documentation. Interested readers can view more of the details from this case—including the original medical record, legal documents, expert witness opinions, and further analysis of the medical care and documentation—at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Inconsistent Records & Insufficient Imaging Complicate Malpractice Case”