Intranasal Fentanyl for Sickle Cell Vaso-Occlusive Pain

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 09 – September 2023Case

A 15-year-old female with sickle cell disease (SCD) presents to your emergency department (ED) with a vaso-occlusive pain episode (VOE) of her legs and back. She has a history of similar episodes. There are no other concerning aspects to her examination. Routine bloodwork was ordered in triage. While waiting for results you wonder if a dose of intranasal (IN) fentanyl could address her pain until intravenous (IV) access can be obtained?

Background

Timely and effective pain control is important for all patients including children. The Pediatric Pain Management Standard1 for children was published this year to provide guidance to health organizations on how to deliver equitable and quality pain management across hospital settings.

Children with SCD often present to the ED in pain due to VOE. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute released an expert panel report in 2014 with evidence-based guidelines for management of SCD recommending timely administration of parenteral opioids for VOE.2 However, multiple barriers including ED crowding, boarding, and staffing shortages contribute to delays in care.

IN fentanyl has been safely used to treat pain in pediatric patients. It offers a way to deliver analgesia without IV access.3,4

Clinical Question

In children with SCD with VOE, how does IN fentanyl impact disposition?

Reference

Rees CA et al. Intranasal fentanyl and discharge from the emergency department among children with sickle cell disease and vaso-occlusive pain: A multicenter pediatric emergency medicine perspective. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(4):620-27

Population: Children aged three to 21 years, with SCD (Hemoglobin SS disease or hemoglobin S-beta thalassemia) who presented to the ED with VOE

Excluded: Children with upper respiratory infection, concern for stroke, altered mental status, or head injury, acute chest

Intervention: IN fentanyl (50 mcg/mL) delivered via atomizer with maximum of 100 mcg

Comparison: No IN fentanyl

Outcomes:

Primary Outcome: Discharge home from the ED

Secondary Outcomes: Dose and route of opioids administered, time of opioid administration, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration, use of IV fluid, time of ED or triage arrival to first opioid administration, time of day patient presented to the ED

Type of Study: Secondary analysis of a cross-sectional study from 20 academic pediatric EDs in the United States and Canada

Authors’ Conclusions

“Children with sickle cell disease who received intranasal fentanyl for vaso-occlusive pain episodes had greater odds of being discharged from the emergency department than those who did not receive it.”

Results

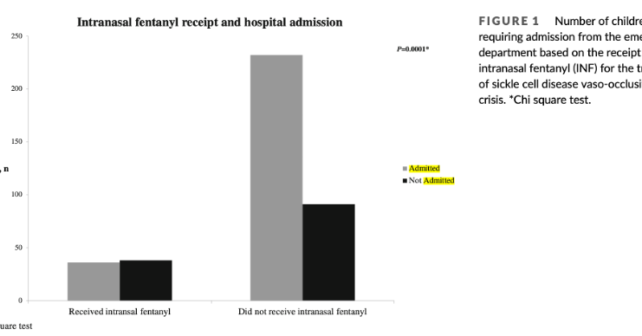

They included 400 patients with 54 percent being female. The median age was 15 years. Most patients (92 percent) had hemoglobin SS disease while the other eight percent had hemoglobin S-beta thalassemia. The overall rate of admission was 67 percent. In this study 19 percent of SCD with VOE received IN fentanyl.

Key Results

IN fentanyl use was associated with greater odds of being discharged from the ED in children with SCD and VOE compared to those who did not receive IN fentanyl.

Primary Outcome: Discharged home from the ED

Secondary Outcomes: There were several secondary outcomes. Two interesting findings were time to parenteral opioid administration and total dose of opioid morphine equivalents. Those who received IN fentanyl had a much greater odds ratio of receiving parenteral opioid within 30 and 60 minutes and received greater amounts of opioids:

≤30 minutes: OR, 9.38; 95 percent CI, 5.22-16.83

≤60 minutes: OR, 9.83; 95 percent CI, 4.87-19.85

Total morphine equivalents IN fentanyl 0.36 mg/kg (SD, 0.14) versus no IN fentanyl 0.22 mg/kg (SD, 0.25)

EBM Commentary

Selection Bias: Investigators from each site reviewed 20 consecutive charts. The annual ED volume of patients with SCD VOE ranged from 80 to 700 per year. It is unclear exactly how the 20 charts were selected for evaluation and if they accurately represented the overall population of SCD patients that sought care for VOE. This opens the potential for selection bias being introduced into the data set.

Time and Dose of Opioid Administration: Children who received IN fentanyl received their first dose of parenteral opioid significantly faster compared to the children who did not. It’s possible that the faster administration of opioid therapy in general plays a bigger role in ability to discharge a SCD patient with VOE than the administration of IN fentanyl. However, the multivariable analysis did not find that timeliness of opioid administration was associated with decreased odds of hospital admission.

Another interesting secondary outcome that could confound the results is that children who received IN fentanyl received higher overall total parenteral opioid morphine equivalents. We would have thought those receiving pain medicine faster would lead to a lower overall total amount of parenteral opioids being used.

External Validity: In this study, 15 out of 20 sites had the ability to administer IN fentanyl. Out of those 15 sites, only 10 sites administered IN fentanyl. Was the use of IN fentanyl simply not part of the institutional culture or not a standardized pathway for treating VOE? Or perhaps patient preferences played a role and IN fentanyl was offered but declined.

There was also a great deal of variation for admission rates which ranged from 45 to 90 percent. Despite this variation in practice, IN fentanyl administration was still associated with discharge even accounting for pain scores and opioid administration. Further, when the analysis includes only sites that administer IN fentanyl, the association is even stronger.

The differences observed in this study make it uncertain if these findings can be generalized outside of these academic settings. However, adopting IN fentanyl administration does not seem difficult and community hospitals may want to consider this treatment option.

Bottom Line

Intranasal fentanyl may be helpful for children with SCD presenting with VOE.

Case Resolution:

You decide to give the patient a dose of IN fentanyl while she is awaiting IV access. After IV access is obtained, she receives a few doses of parenteral morphine and tells you that she feels like her pain is much better controlled. She is discharged from the ED.

Thank you to Dr. Dennis Ren for his help on this critical appraisal. He is a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, DC.

Remember to be skeptical of anything you learn, even if you heard it on the Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine.

References

- Campbell F, Hudspith M, Choinière M, et al. An action plan for pain in Canada. Health Canada website. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2021-rapport/report-rapport-2021-eng.pdf. Published May 2021. Accessed August 8, 2023.

- National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute. Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease: Expert panel report, 2014. National Institutes of Health website. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/evidence-based-management-sickle-cell-disease. Published 2014. Accessed August 8, 2023.

- Murphy A, O‘Sullivan R, Wakai A, et al. Intranasal fentanyl for the management of acute pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(10):CD009942.

- Murphy A, O‘Sullivan R, Wakai A, et al. Intranasal fentanyl for the management of acute pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(10):CD009942.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Intranasal Fentanyl for Sickle Cell Vaso-Occlusive Pain”