The EMCrit call/response checklist offers tips to prepare patients and ED teams, gather equipment needed to perform safe, successful intubations

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 03 – March 2014The Case

A 63-year-old male with severe sepsis from pneumonia is brought to the emergency department. The monitor shows blood pressure of 72/48 mm Hg and a blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 92 percent. The decision is made to intubate the patient for predicted worsening clinical course as well as poor mental status. What now? Just jump into rapid sequence intubation (RSI), right? But it’s pretty disappointing to realize that the patient’s blood pressure has dropped even lower after you push the meds, and he has turned out to be an unanticipated difficult airway. You yell for the necessary equipment and meds, but nobody seems to understand the seriousness of the situation.

Wouldn’t it be better to make sure everything was prepared to give you optimal success every time whether the intubation is smooth or difficult? This is a situation ripe for a checklist.

Not Everyone Respects Checklists

From a doctor on a critical-care mailing list, regarding a checklist: “This is so over the top! Instead of using a checklist, I just intubate. Sorry for sounding gung ho. Many of the items on the checklist are required to be on standby 24-7 in every ED. No point to go through them. Briefing is clearly superfluous and a waste of time. The checklist obsession just got worse!”

You may think a checklist is unnecessary, but think again. In 2001, Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, introduced an intensive-care checklist protocol for central venous catheter insertion.1 In the first three months of use after the launch of the Keystone ICU project, the median rate of infections at a typical ICU dropped from 2.7 per 1,000 patients to 0.2 An estimated 1,500 lives and $175 million were saved over the first 18-month period.1 Since this landmark study showing the efficacy of a checklist, medicine has begun to embrace the idea of integrating these cognitive aids into clinical practice. Most checklists have been adopted in elective procedures, where the controlled and stable setting allows for the time and patience to run through the list. However, we can likely gain similar safety and cognitive benefits from checklists for ED intubations.

Every time the decision is made to intubate, we are putting patients at risk. It is imperative to consider and prepare for predictable dangers, especially when intubating in an adrenaline-charged environment like the ED. The EMCrit call/response intubation checklist is designed for use in such a situation.

How to Use the EMCrit Call/Response Intubation Checklist

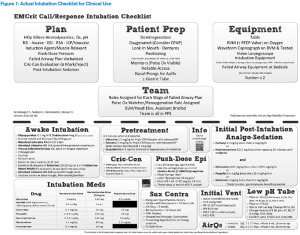

The checklist (Figure 1) is available at emcrit.org/podcasts/emcrit-intubation-checklist. Print the checklist double-sided on a single piece of paper. Fold it in half along the dotted line on the front page; only the top portion of the page is the actual checklist to be used while intubating. The bottom of the front page is an aid for commonly needed doses and reminders for the peri-intubation period. The back (inside the fold) includes instructions for the use of the checklist—these should only be used for review or to teach others in nonclinical situations.

With a call/response checklist, one person should go through the list and ask the questions while another member of the intubating team, ideally the intubator, provides the answers. By the time the checklist has been completed, all equipment gathering and preparations have already been accomplished. In this case, the checklist takes less than a minute to run through. It only takes longer when items have been forgotten.

Figure 1: Actual Intubation Checklist for Clinical Use

Visit emcrit.org/podcasts/emcrit-intubation-checklist to download.

Understanding the Items on the Checklist Plan Section

Think about the presence of the “HOp Killers”: hemodynamic kills, oxygenation kills, and pH kills. Issues such as preexisting hypotension, poor cardiac output, poor oxygenation, and metabolic acidosis may cause patients to destabilize and code in the peri-intubation period. This is a reminder to address these issues before the tube, choose strategies based on their presence, and prepare for further decompensation.

Next, consider the approach to intubation: RSI/DSI/RSA/Awake/ICP-Vascular. RSI is our default management strategy in EM. Delayed sequence intubation (DSI) might be beneficial in those patients not allowing pre-oxygenation due to delirium or altered mental status. Rapid sequence airway (RSA) may be used for patients who need to be bagged during the apneic period (i.e., severe metabolic acidosis). The technique consists of induction and paralysis immediately followed by placement of a supraglottic airway (SGA) to allow safe apneic-period bagging. When patients have fully relaxed, the device is removed, and you are ready to intubate. Consider awake intubation when you predict patients to be a difficult airway and you have a few minutes to prepare for an awake look. The intracranial pressure (ICP)/vascular approach refers to situations in which there is great concern about a peri-intubation blood pressure spike (eg, subarachnoid hemorrhages, aortic dissections, and head trauma). Once the approach is determined, choose the induction agent and muscle relaxant. On the bottom of the front page, there is a table for intubation medications and their dosages.

Figure 2: Supplemental Information for Reference

Visit emcrit.org/podcasts/emcrit-intubation-checklist to download.

Other things to think about during this planning stage are push-dose pressors in patients who are already hypotensive or have the potential to drop their blood pressures, a failed-airway plan, cric-con evaluation (evaluation and possible marking of the cricothyroid membrane), and post-intubation medications. The push-dose epinephrine will help raise blood pressure and increase cardiac output; mixing instructions are found on the bottom half of the sheet. The failed-airway plan and sequencing should be verbalized and discussed among the team so everyone in the room is on the same page. For instance, specify who will try the first, second, and third attempts and what changes are to be made between each one. After a failed third attempt, state, “We’ll try SGA, and if that fails, then we’ll move on to a cricothyroidotomy.” Lastly, have the post-intubation analgesics and sedatives prepared prior to the intubation to avoid having paralyzed patients in pain crying while they wait for the meds. There is a table of analgesia and sedation medications, with their dosages, on the bottom of the fold.

Patient Preparation

After the plan has been developed, you’re ready to move on to the “Patient Prep.” It is important to think about denitrogenation and oxygenation separately. To denitrogenate, or replace the nitrogen in the lungs with oxygen, patients will need at least eight vital-capacity breaths or three minutes on a high FiO2 oxygen source. For oxygenation, the goal oxygen saturation is more than 95 percent. If that is difficult to achieve with a nasal cannula/non-rebreather mask (NC/NRB) combination, consider CPAP or allowing the patient to breathe spontaneously through a bag valve mask (BVM) with a PEEP valve and a nasal cannula underneath. Next, ensure proper patient positioning for a safe intubation: face plane parallel to ceiling, ear-to-sternal notch, head of bed 30 degrees up to help with preoxygenation and glottic exposure. If patients are in a cervical collar, use reverse Trendelenburg. Verify that the monitors are functioning with accurate blood pressure readings, adherent ECG leads, etc.; there must be a reliable pulse oximeter, preferably visible to the intubator and whomever is overseeing the intubation. Assign a person to call out when the saturation hits 93 percent, the point at which patients should be reoxygenated. Patients must also have reliable IV or IO access. A nasal cannula should be placed on patients for preoxygenation and apneic oxygenation. Consider placing a gastric tube if patients have a gastrointestinal bleed or small bowel obstruction.

Every time the decision is made to intubate, we are putting patients at risk. It is imperative to consider and prepare for predictable dangers.

Equipment

Next, check the intubation equipment. There must be a table for the location of equipment; placing supplies on the patient bed guarantees they will be on the floor when you need them most. The BVM should have oxygen turned up high and include a PEEP valve if the oxygenation HOp Killer is present. Test the waveform capnograph and place it between the bag and the mask of the BVM. Have the intubation supplies, including a backup standard laryngoscope, a video laryngoscope, and all of the failed-airway equipment, at the bedside to enact the previously verbalized plan if necessary. There should also be two syringes, an appropriately sized oropharyngeal airway, a stylet, a tube-securing device, and two functioning sources of suction.

The Team

Finally, brief the team. Assign roles for each stage of the failed-airway plan. Assign a pulse-ox watcher to call out at 93 percent. Brief the assisting staff on what is expected of them. Ensure that all of the team is in personal protective equipment (PPE), which at a minimum should include eye protection and a surgical mask.

Conclusion

Every intubation means taking a patient’s life into your hands. Extensive planning and preparation is imperative. This checklist may help with the meticulous organization that is necessary to make certain the intubation will be as safe as possible. For more information or the podcast on this checklist, please refer to emcrit.org/podcasts/emcrit-intubation-checklist.

Scott D. Weingart, MD, FCCM, is an ED intensivist. This column is a distillation of the best material from the EMCrit Blog and Podcast (http://emcrit.org).

Scott D. Weingart, MD, FCCM, is an ED intensivist. This column is a distillation of the best material from the EMCrit Blog and Podcast (http://emcrit.org).

Angela Hua, MD, is a housestaff physician at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York and on the Emergency Medicine Resident Committee of the ACEP New York chapter.

Angela Hua, MD, is a housestaff physician at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York and on the Emergency Medicine Resident Committee of the ACEP New York chapter.

References

- Gawande, A. The Checklist: if something so simple can transform intensive care, what else can it do? New Yorker. Available at: www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/12/10/071210fa_fact_gawande?currentPage=all.

- Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355 (26):2725-32.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “An Intubation Checklist for Emergency Department Physicians”