Explore This Issue

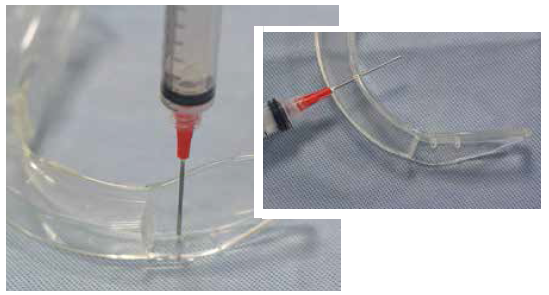

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 02 – February 2015Figure 1. Equipment used to make this laryngoscope tool.

The Case

A 42-year-old female presents to the emergency department after sustaining blunt facial trauma from a high-speed motor vehicle collision. She weighs more than 400 pounds and is back-boarded and collared. Blood is flowing freely from her mouth, and she is unresponsive to painful stimuli and gurgling with each respiration; this patient needs her airway secured five minutes ago. After the newly minted intern gives it a shot by direct laryngoscopy and pulls out with a look that says, “I think I just soiled my pants,” you step in. Using the GlideScope this time, you visualize the epiglottis, but then a splattering of

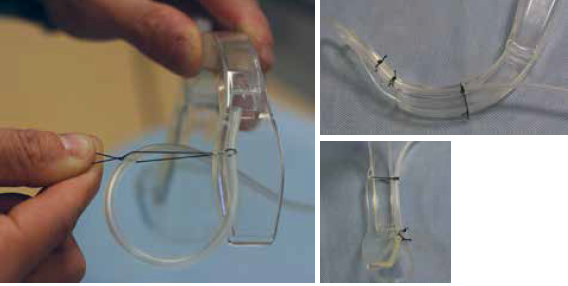

Figure 2. Cut the distal end of the IV tubing at an oblique angle.

blood hits the lens of your GlideScope and obscures the view. You try again with the same result. Is it time to dust off the #11 blade, or is there an alternative trick of the trade to improve visualization?

Background

In 1944, Bannister and Macbeth described direct laryngoscopy by aligning the pharyngeal, laryngeal, and oral axes to obtain direct visualization of the glottic inlet.1 Aligning these axes and visualizing the glottic inlet can be easily complicated by difficult airway characteristics (eg, large tongue, short neck, small mandible, bodily fluids in the airway, cervical immobility, facial trauma, edema, or limited mouth opening).2 Prior to the advent of video laryngoscopy, physicians had limited options to handle these complications before proceeding to a surgical airway. Video laryngoscopy can help circumvent these obstacles and has been shown to improve glottic visualization, especially in difficult airways.3 The hyperacute angle of the GlideScope can navigate challenging anatomy, and the video

Figure 3. Fit the luer lock into the oblique IV tubing opening.

display provides a way to supervise novice operators. However, there is no solution for when the video laryngoscope’s view becomes obscured by bodily fluids. Removing the laryngoscope to clean it off wastes time and subjects the patient to another intubation attempt. To assist with clearing secretions, video laryngoscopes have been augmented using an inline suction device attached to the blade of the laryngoscope, but the results showed no improvement in time to intubation or increased success rates.4 Furthermore, the study did not address the complication of getting the secretions off of the screen to allow for better visualization.

To assist with clearing secretions, video laryngoscopes have been augmented using an inline suction device attached to the blade of the laryngoscope, but the results showed no improvement in time to intubation or increased success rates.4

Technique

Attaching IV tubing to a video laryngoscope can help improve visualization during

Figure 4. Use the syringe to make three holes in the laryngoscope blade.

intubation. This novel apparatus will take approximately 20 minutes to assemble, so it should be put together prior to when it is needed. You can assemble it during your next night shift at 3:30 am and store it with your airway supplies. While the example below is applied to the GlideScope, this principle and assembly can also be applied to most other video laryngoscopes (eg, Karl Storz C-MAC).

Equipment Needed (see Figure 1)

- 10 cc syringe with 18 g blunt-tip needle

- One set of IV tubing

- Scissors

- Tape

- 0-0 silk suture

- Normal saline flush

- GlideScope disposable laryngoscope blade

- One needleless luer lock

Assembly

1. Cut the IV tubing as shown in Figure 2. Cut the distal end of the IV tubing at an oblique angle and fit the luer lock into the oblique opening. This may be take some elbow grease, but it will fit (Figure 3).

2. Use a 10 cc syringe with the 18 g needle as a drill and make the three individual holes as outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 5. Fasten the IV tubing to the laryngoscope blade with 0-0 silk with the knot tied on the lateral aspect of the laryngoscope.

3. Fasten the IV tubing to the laryngoscope blade with 0-0 silk with the knot tied on the lateral aspect of the laryngoscope, avoiding any further obstruction of the GlideScope view (Figure 5). The end of the IV tubing should be secured in the corner of the laryngoscope blade within 0.5 cm of the lens. Additional holes can be made to further secure the IV tubing if needed.

Figure 6. Attach the remainder of the IV tubing to laryngoscope blade with tape.

4. The remainder of the IV tubing can be attached to laryngoscope blade with tape (Figure 6).

Utilization

1. The same technique for any GlideScope intubation is used with this apparatus: entering the oropharynx midline, rotating the blade, and visualizing the glottis.

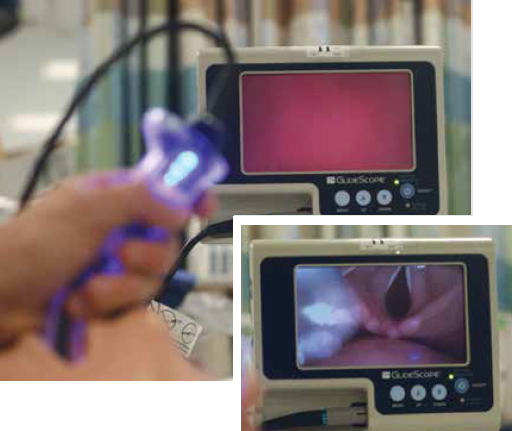

2. If the lens becomes obscured by bodily fluid during the intubation, the operator or assistant can push 5 mL increments of normal saline through the IV tubing to clean the lens (Figure 7). This can be repeated as many times as needed to obtain a clear view and intubate the patient (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Push 5 mL increments of normal saline through the IV tubing to clean the lens.

Patient Selection

This apparatus could arguably be used with any intubation for which you are using video laryngoscopy. Our current bedside difficult-airway prediction tools are limited at best, and the rate of unexpected difficult airways has been shown to be as high as 52 percent even in controlled anesthesia settings.5,6 The most obvious patients who can benefit from this tool are those who are bubbling, bloody, or blowing chunks. In other words, patients who have significant bubbling pulmonary edema, have a traumatic bloody airway, or are actively vomiting (ie, blowing chunks), all of which could obscure the video

Figure 8. Intubated patient.

laryngoscope’s lens.

Caution

There may be concern that the additional saline within the oropharynx may put the patient at further risk of aspiration. However, the risk is theoretical and likely the lesser of two evils when considering such time-sensitive airways. While this product may provide improved visualization of the airway on simulated intubations, it has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and therefore cautious use is recommended at the discretion of the provider.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McNamee is chief resident of the emergency medicine residency at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McNamee is chief resident of the emergency medicine residency at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

References

- Bannister FB, Macbeth RG. Direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. Lancet. 1944;244:651-654.

- Mosier J, Whitmore S, Bloom J, et al. Video laryngoscopy improves intubation success and reduces esophageal intubations compared to direct laryngoscopy in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2013;17:R237.

- Griesdale D, Liu D, McKinney J, et al. Glidescope video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:41-52.

- Lipe DN, Lindstrom R, Tauferner D, et al. Evaluation of Karl Storz CMAC Tip device versus traditional airway suction in a cadaver model. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15:548-553.

- Paix AD, Williamson JA, Runciman WB. Crisis in management during anaesthesia: difficult intubation. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:e5.

- Shiga T, Wajima Z, Inoue T, et al. Predicting difficult intubation in apparently normal patients: a meta-analysis of bedside screening test performance. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:429-437.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “Keep Video Laryngoscope Clear with IV Tubing, Saline, and Some Ingenuity”

March 9, 2015

Kyle StevensWould love to see video of this DYI setup and of it in action

August 30, 2025

Frankfor hands free use:

attach a one way valve to an extension tubing. cut the other end of the extension tubing to length and fasten it to the blade as described. store it with your airway supplies.

To use the system connect a 100ml saline soft bottle to a regular iv tubing. connect the open end of the iv tubing to the one way valve on the blade. put the bottle on the ground, regulate the saline flow by pressing down your foot on the soft bottle.