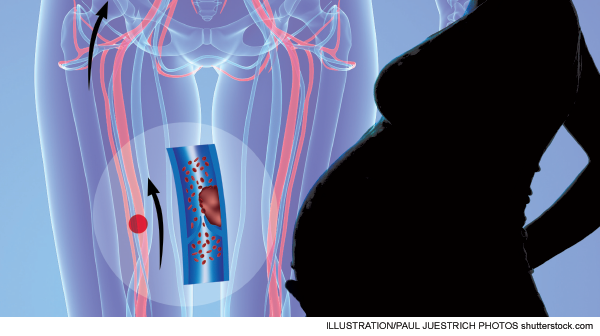

Common assessment methods including clinical decision rules, D-dimers, and PERC rules have limited use in detecting VTE in pregnancy

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014With so much debate and controversy regarding the evaluation of venothromboembolic disease (VTE) and with much of the debate centering on methods of risk stratification to avoid the expense and risks associated with overtesting, it is very easy to overlook patients who just don’t belong in this discussion.

You like clinical decision rules (CDRs)? Great! You can cast your vote for which ones you like, when to apply them, to whom they should apply, what pre-test probabilities are acceptable for assigning low risk, and, of course, which have been adequately validated.

You’re a D-dimer fan? Fine! (For now.) Which D-dimer are you using, is your D-dimer “highly sensitive,” what is the post-test probability for a negative test, and what should you do with positive results?

There are many good questions and many good debates, which will eventually lead to even better answers.

Surprisingly, VTE in pregnancy has been conspicuously absent from the data that are guiding these discussions, and that absence of data, from my perspective, makes decision-making in this at-risk population pretty easy. In short, if you have clinical suspicion, you should probably just study ’em all. Heresy! Just irradiate all of those expectant mothers?! No, not exactly. In an attempt to do the right thing, physicians may feel that the lack of evidence in this population seems to point to evaluation in favor of cost reduction, reduced radiation exposure, etc. The lesser of two evils is diagnostic evaluation when the alternative is missed or delayed diagnoses. Remember, the short answer on risk stratification is that these patients are not low-risk patients and should not be classified as such.

Let’s examine four essential areas of the VTE debate, but in the specific context of pregnancy: risk, CDRs, D-dimers, and ultrasound evaluation.

The data are clear; VTE is pregnancy is more common than many think. Marik and Plante published an excellent review in 2008 that highlighted some important statistics about VTE in pregnancy.1 The incidence of VTE in pregnancy is estimated to be 0.76–1.72 per 1,000 pregnancies, indicating four times the risk compared to nonpregnant patients. Two-thirds of DVTs occur prior to delivery (antepartum) and are equally distributed among all three trimesters, and 43–60 percent of pregnancy-related pulmonary emobli (PE) occur in puerperium (roughly the six-week time period extending from delivery). Greer reported similar findings in his review: “The relative risk of antenatal VTE is approximately fivefold higher in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women of the same age.”2 He also reported the absolute risk to be 1 in 1,000 pregnancies. Most interesting is that 50 percent of VTE cases occur in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (early pregnancy); many clinicians are under the misconception that this is a relatively low-risk gestational period. Puerperium was similarly reported as the period with the highest risk, with a relative risk of 20-fold. This article also provides some insight as to risk factors: previous VTE (odds ratio 24.8), immobilization (7.7), BMI >30 (5.3), BMI >25 combined with immobilization (62), smoking (2.7), preeclampsia (3.1), and C-section (3.6).

In a more recent cross-sectional study, the incidence of VTE was quoted as 2.5 per 1,000 natural pregnancies and 4.2 per 1,000 pregnancies from in vitro fertilization.3

CDRs will lead clinicians to one place in pregnant patients: the wrong answer. Wells is the most validated CDR for deep venous thrombosis but has not been validated in pregnancy.4 Furthermore, neither has the Wells PE rule.4 Physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy alter the physiologic parameters that are often incorporated into VTE CDRs. Edema and leg pain are common in pregnancy. In addition, dyspnea is a common complaint in pregnancy.4 Respiratory rates are also known to increase during pregnancy.

If CDRs can’t put patients in a low-risk category (low pre-test probability), then discussion about D-dimer use in pregnancy should be moot. However, in a desire to reduce radiation exposure in pregnant patients, D-dimer tests are often ordered in this population. D-dimer levels increase throughout pregnancy, beginning in the first trimester, and by 35 weeks, all will be above the cut-off level of 500mcg/L.4 This normal physiologic phenomenon has prompted some investigators to increase the cut-off level for D-dimer in pregnancy. Although false positives clearly occur in pregnancy, it seems to be a flawed strategy to increase the cut-off to avoid false positives at the risk of increasing false negatives. Such changes are under investigation and should be adopted with caution.

If D-dimer is problematic in pregnancy, why not use the PERC rule? PERC is most likely the preferred CDR in current use. However, in the derivation study, six clinical variables were deemed “nonsignificant”: pleuritic chest pain, substernal chest pain, syncope, smoking status, malignancy, and pregnancy or immediate postpartum status.5 Kline and Slattery later reported three factors that were associated with PERC-negative PE. Interestingly, they were pleuritic chest pain, pregnancy, and postpartum status.6 Perhaps removal of these three should be called into question. If nothing else, this certainly limits the PERC rule’s application in pregnancy.

In order to reduce potential radiation exposure, many are recommending that compression ultrasonography be used first in pregnant patients as opposed to computed tomography pulmonary angiogram.4 This approach certainly has merit, particularly in pregnant patients with leg complaints. However, it also has some drawbacks. Venous flow velocity reduces approximately 50 percent in the legs by weeks 25–29 of pregnancy, possibly impacting image interpretation, and isolated iliac vein thrombosis is more common in pregnancy and is difficult to diagnose.1

Use caution with pregnant patients who may have VTE. Although our goal is to reduce radiation exposure to the fetus and mother, applying evidence from nonpregnant populations can be disastrous. We must be mindful to avoid unnecessary testing, but the use of CDRs and D-dimers, in particular, have little place—if any—in the risk stratification of pregnant patients.

Dr. Klauer is director of the Center for Emergency Medical Education (CEME) and chief medical officer for Emergency Medicine Physicians, Ltd., Canton, Ohio; on the Board of Directors for Physicians Specialty Limited Risk Retention Group; assistant clinical professor at Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine; and medical editor-in-chief of ACEP Now.

References

- Marik PD, Plante LA. Venous thromboembolic disease and pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2025-2033.

- Greer IA. Thrombosis in pregnancy: updates in diagnosis and management. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012;2012:203-207.

- Henriksson P, Westerlund E, Wallén H, et al. Incidence of pulmonary and venous thromboembolism in pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2013;346:e8632.

- Tan M, Huisman MV. The diagnostic management of acute venous thromboembolism during pregnancy: recent advancements and unresolved issues. Thromb Res. 2011;127(Suppl 3):S13-S16.

- Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Kabrhel C, et al. Clinical criteria to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1247-1255.

- Kline JA, Slattery D, O’Neil BJ, et al. Clinical features of patients with pulmonary embolism and a negative PERC rule result. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:122-124.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Lack of Data for Evaluating Venothromboembolic Disease In Pregnant Patients Leaves Physicians Looking for Best Approach”