A 37-year-old female was walking home from grocery shopping when she had an encounter with a stray pit bull. For obvious reasons, all history was obtained via emergency medical services and Cleveland police. They were called to the scene to find her with a blood pressure of 135/85, pulse of 110 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 26 per minute. The major injury was to her face and neck, with lacerations and bites to her legs.

Explore This Issue

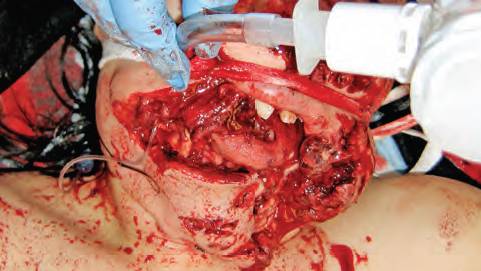

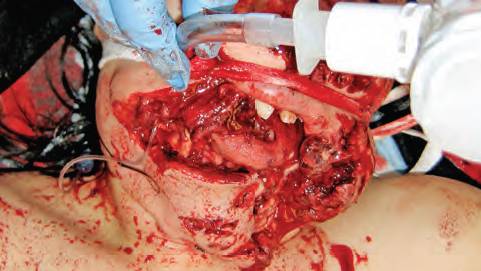

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 10 – October 2023On arrival to the emergency department (ED) she was awake and breathing with stridor. A tracheostomy was considered, but her trachea appeared to be grossly intact and her vocal cords were visible through her wounds. She was intubated with the assistance of bougie and ketamine, and her appearance after intubation is pictured above.

The patient was intubated successfully as the vocal cords were visible through the wound and the trachea appeared to be intact.

Overview

Laryngotracheal wounds occur rarely, whether blunt or penetrating. The larynx is generally protected from blunt injury by the mandible and sternum. These injuries’ significance lies, of course, in their high mortality rate. While they constitute less than one percent of all traumatic injuries, laryngeal injury is the second most common cause of death (after intracranial injuries) in patients with head and neck injuries.1 Missing a significant laryngotracheal injury can lead to airway obstruction and death. Injuries involving the cricoid cartilage are particularly lethal because of asphyxia from airway obstruction, edema, or hematoma. Patients with small lacerations or abrasions of the larynx or trachea may be managed conservatively with close observation, steroids, and serial endoscopy.

Laryngeal trauma occurs in one in 14,000 to one in 30,000 ED visits. Laryngotracheal trauma has been cited as accounting for less than one in 100,000 hospital admissions.2 As noted above, one major reason for its rarity is that the larynx is protected by the mandible, sternum, and cervical spine.

In children, the larynx is at the level of C4, and protected by the mandible. Fracturing the larynx requires considerable force, and the great majority of fractures are from blunt high-velocity trauma. These include motor vehicle crashes, sports injury, and penetrating neck injuries.3

The most severe occurrence is generally the “clothesline” injury, in which a motorcyclist, dirt biker, or snowmobiler hits a fixed item such as barbed wire, fencing net, or a tree branch, thus striking the front of the neck below the helmet. This mechanism may cause crumbling injury to the cartilage or a laryngotracheal separation. It is noteworthy that trauma to the trachea and larynx may be accompanied by vascular damage to the carotid arteries, jugular veins, or esophagus. The example in this case notwithstanding, motor vehicle crashes are the most common cause of laryngeal injuries.1

Blunt laryngeal injuries may occur from blunt trauma during fights or sports. Airway obstruction may be immediate or delayed. Unstable patients should have an airway established, generally by tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy. Devascularization and scarring of tissue might result in long-term obstruction. Any intralaryngeal mucosal injury is likely to produce some degree of granulation tissue, which may lead to scarring or obstruction. Prompt repair of the mucosa and avoidance of exposed cartilage is critical. Even with optimal care, patients may become dependent on a tracheostomy and/or gastrostomy in the long term.4

Laryngeal injuries may also be classified based on the anatomical site and the structures involved:

- Type 1: Supraglottic: epiglottic hematoma or avulsion; hyoid bone fracture; thyroid cartilage fracture; arytenoid dislocation or degloving; endolaryngeal edema; airway obstruction

- Type 2: Glottic injuries: hoarseness (generally associated with thyroid-cartilage fracture); vocal-cord edema; endolaryngeal lacerations; or avulsion of vocal cords from the anterior commissure

- Type 3: Subglottic injuries: involvement of the cricoid cartilage and trachea with airway compromise; complete cricotracheal disruption with airway obstruction that may be rapidly fatal.7

For completeness, four varieties of laryngeal fracture have been described:

- Supraglottic laryngeal fracture with posterior displacement of the epiglottis and laryngeal inlet

- Cricotracheal separation

- Vertical midline fracture, damaging the anterior commissure and separating the thyroid alae

- Comminuted fracture: more commonly encountered in the older, rigid, and calcified larynx.8

Initial evaluation starts with the history: blunt or penetrating, polytrauma or other injuries, and whether the patient is coherent and cooperative or has an altered voice. Does the patient have difficulty breathing or swallowing? The primary management of laryngeal injuries is to evaluate and establish an airway.

The physical examination, as always, follows airway, breathing, circulation, evaluation of cervical spine. Is the patient stridorous or hoarse? The thyroid cartilage should be checked for prominence or loss thereof. The neck should be palpated for subcutaneous air. Is there respiratory distress or a neck hematoma? Is there an open neck wound or palpable cartilage fracture? The patient should be evaluated for hemoptysis, cough, sternal retractions, thrill, or bruit.

Flexible laryngoscopy, CT scan, direct laryngoscopy under general anesthesia, esophagoscopy, ultrasound, or chest X-ray may all be requested by the surgical consultant. If the airway is deemed to be stable, flexible fiber-optic laryngoscopy and computed tomography of the neck may be appropriate initial studies. Flexible laryngoscopy is used to evaluate mucosal tissues of the larynx and upper digestive tract after the primary and secondary trauma surveys are completed. Edema, laryngeal lacerations, mucosal tears, hematomas, exposed muscle, and vocal-cord paralysis or paresis may be diagnosed in such fashion.

Reconstructive computed tomography can assess the laryngeal framework to avoid missing laryngeal fracture and, hopefully, long-term comorbidities. Non-contrast CT can evaluate the cartilaginous and bony components of the hyoid and larynx. Depending on availability and local expertise, videostroboscopy of the larynx and electromyography of the larynx may be performed by the appropriate consultants.

For Schaefer type 1 and 2 injuries, close monitoring is recommended, along with intravenous dexamethasone and nebulized steroids. Conservative management entails observation, elevation of the head of the bed, steam inhalation, voice rest, and IV corticosteroids.

If the patient needs surgical exploration, tracheostomy is the recommended intervention to secure the airway. Early exploration and reconstruction of the laryngeal framework is generally recommended to preserve laryngeal function and to restore normal phonation. Surgical exploration and correction of fractures may utilize mini-plates, 3-D plates, bioresorbable plates, Montgomery intralaryngeal stent, thread, steel wires, titanium mesh to fix fractured laryngeal cartilage, or titanium plates.3

The patient was intubated successfully, in the ED under direct vision, as the vocal cords were visible through the wound and the trachea appeared to be intact. An endotracheal tube (ETT) was placed over a bougie. She was transported to the operating suite where a tracheostomy was performed. Significant mucosal lacerations were encountered. The mucosa was repaired to ensure coverage and to prevent scarring. Reduction of laryngeal fractures with fixation was accomplished. A minor esophageal injury was repaired. Soft tissue and skin were repaired last. She was given tube feedings for approximately one week. Major vessels were unharmed per neck CT with contrast. The tracheostomy was kept in place until the larynx was fully healed. She is currently undergoing therapy with a speech pathologist.

While her long-term result is still evolving, it is important to note that complications of laryngeal injuries may be both acute and chronic. Acute complications are upper-airway obstruction and asphyxia. Recurrent nerve injury, hematoma, infection, and death are possible. Chronic complications may cause problems which may cause patients to present to the ED: vocal-cord paralysis; chronic aspiration; recurrent granulation formation; hoarseness; supraglottic, glottic, subglottic, or tracheal stenosis; and recurrent laryngeal nerve dysfunction.

The Difficult Airway: A Brief Overview of the Airway Disruption Algorithm

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) in 2005 modified the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm.9 A surgical airway may be the best choice in patients with oromaxillofacial trauma. In this particular case, a tracheostomy could be performed in the operating suite under somewhat controlled circumstances. More recent ASA guidelines suggest awake intubation for airway disruption if there is a major laryngeal, tracheal, or bronchial tear, provided that the patient is awake, cooperative, hemodynamically stable, and able to maintain adequate oxygen saturation.10 For infralaryngeal and tracheal injury, recommendations include rapid sequence intubation or direct laryngoscopy (perhaps video-assisted) with a flexible intubation scope with an appropriately sized ETT already loaded over it. The ETT is then introduced over the flexible intubation scope with the cuff positioned over the airway. Positive-pressure ventilation and transtracheal jet ventilation should be avoided proximal to an infralaryngeal tear.10

Dr. Glauser is faculty at the Case Western Reserve University/MetroHealth Medical Center/Cleveland Clinic emergency medicine residency program in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Effron is faculty at the Case Western Reserve University/MetroHealth Medical Center/Cleveland Clinic emergency medicine residency program in Cleveland, Ohio.

References

- Malvi A, Jain S. Laryngeal trauma, its types and management. Cereus. 2022;14(10): e29877.

- Schaeffer SD. The acute management of external laryngeal trauma. A 27-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(6):598-604.

- Rai S, Anjum F. Laryngeal fracture. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing 2023. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562276/. Accessed September 16, 2023.

- Shaker K, Winters R. Laryngeal Injury. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing 2023. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556150/. Accessed September 16, 2023.

- Schaefer SD. Management of acute blunt and penetrating external laryngeal trauma. The Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):233-44.

- Moonsamy P, Sachdeva UM, Morse CR. Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7:210-216.

- Bell RB, Verschueren DS, Dierks EJ. Management of laryngeal trauma. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20(3):415-30.

- Flood LM, Astley B. Anesthetic management of acute laryngeal trauma. Br J Anesth. 1982;54(12):1339-43

- Wilson WC. Trauma airway management. ASA Newsl. 2005;69(11):9-16

- Hagberg CA, Kaslow O. Difficult airway management algorithm in trauma updated by COTEP. American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2014;78(9):56-60.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Laryngeal Injuries: An Introduction”