The Case

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath. She checked into the emergency department at 3:41 a.m. with respiratory symptoms. She had a complex history including type 1 diabetes, end-stage renal disease on dialysis, tetralogy of Fallot, and a partial pancreatectomy. Her triage vitals showed a blood pressure of 177/97, a pulse of 86 beats per minute, a pulse oximetry of 94 percent on room air, and a temperature of 98.7° F.

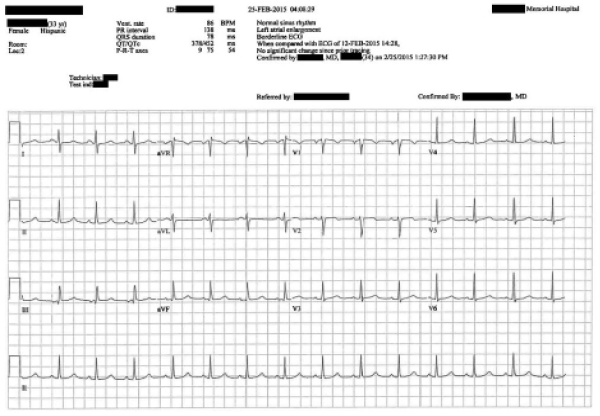

She was seen by an emergency physician. The history noted that her shortness of breath started at 7 p.m., about 8.5 hours earlier. It was worsened by lying flat and improved when she was sitting upright. She had been dialyzed one day earlier. The examination revealed normal breath sounds and no cardiac abnormality. No significant abnormalities were noted on her examination. Laboratory orders included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, troponin, pro-brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), chest X-ray, and an ECG. The results were noteworthy for a hemoglobin of 7.7 g/dL, glucose of 418 mg/dL, creatinine of 3.9 mg/dL, BNP >5,000 pg/mL, and negative troponin.

The ECG is shown in Figure 1.

Her chest X-ray was read as “Stable cardiomegaly. There is pulmonary vascular congestion and interstitial infiltrates. Findings suggest fluid overload with congestive failure.”

After reviewing these results, the physician ordered 15 units of insulin SQ (Humulin R). The patient was feeling nauseated and in pain, and so she was given ondansetron 4 mg oral disintegrating tablet and an intramuscular dose of hydromorphone 1 mg. After IV access was obtained, she was given a repeat dose of hydromorphone 1 mg.

Her blood glucose improved to 313 mg/dL. The doctor reassessed the patient, and she was doing well (see Figure 2). Given her reassuring vitals and improving blood glucose, she was discharged from the emergency department.

Figure 2: Progress note before discharge.

The discharge instructions advised her to follow up at her next scheduled dialysis appointment the next day and to return if her symptoms worsened. After she was discharged, she was taken back to the lobby of the emergency department, where she was going to wait several hours for a ride home.

Around 7:25 a.m., another patient in the waiting room suddenly came to the front desk to report that the patient had collapsed.

She was rushed back into the emergency department, where it was discovered that she was pulseless. After a few minutes of chest compressions, return of spontaneous circulation occurred. She was given calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate due to suspicion for hyperkalemia, but her potassium was only 4.3 mmol/L on repeat blood work. She was intubated and admitted to the ICU.

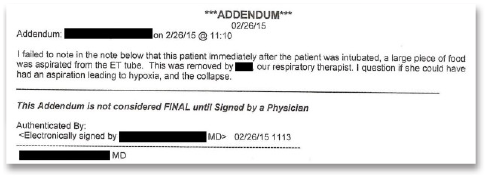

Later that day, the emergency physician who intubated her went back to the chart and made an addendum (see Figure 3)

Figure 3: Chart addendum about a piece of food in the endotracheal tube during intubation.

The patient survived but suffered a devastating anoxic brain injury and now requires 24-7 care in a nursing home.

The patient’s family filed a lawsuit. They alleged that the physician who cared for her was negligent in giving her hydromorphone, likely contributing to a respiratory arrest. They also allege that the dose of insulin caused a hypoglycemic event that caused cerebral damage. The family also made an accusation of an EMTALA violation for not appropriately screening and stabilizing the patient’s emergency medical condition.

The two sides reached a confidential settlement before trial.

Discussion

This case is unique in that there is no single clear cause of her collapse in the waiting room. There are several credible theories:

- It was later discovered that the patient had an allergy to hydromorphone. However, there was no record of the type of reaction. The way it was previously documented in the medical record meant it did not pull into the emergency physician’s note. While it was technically available for review, this fact was buried deep in the patient’s chart. This highlights the danger of medical software with poor functionality and user interfaces.

- The two doses of hydromorphone could have simply caused respiratory depression. They were given one to two hours before she collapsed in the waiting room. In an otherwise healthy patient, this dose would not be expected to cause apnea, but this patient already had underlying pulmonary edema and complained of shortness of breath.

- She may have aspirated or choked on food in the waiting room. The doctor who ran the code noted that a piece of food was removed from the endotracheal tube. Unfortunately, the physician went back and made an addendum to the chart to mention the possibility of aspiration. This led the plaintiff to suggest that he simply wrote this to try to pass liability to the patient.

- The patient may have suffered an arrhythmia in the waiting room. She had underlying cardiac issues (tetralogy of Fallot), history of cardiac surgeries, and predisposition to hyperkalemia. However, her ECG was reassuring, and she had a normal potassium level before and after the code.

The exact cause of the bad outcome is impossible to determine with any certainty. In all likelihood, it was probably multifactorial. Any one of these factors alone would likely not have caused her cardiac arrest, but the combination of several issues superimposed on her chronically ill state were ultimately catastrophic. Emergency physicians are wise to document carefully and understand the implications when making delayed addenda in the medical record. While correcting medical records when something has been left out is certainly appropriate, these will be viewed very suspiciously in retrospect.

Read the full medical record from this case.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Lesson Learned: Delayed Documentation Can Lead to Suspicion”

October 24, 2021

Anthony PohlgeersThere will always be suspicion in anything we document. Not documenting this finding would also be suspicious; especially if it came out in RN or RT testimony later. This addendum was timed appropriately and certainly while the patient was fresh to the ICU and when ‘final outcome’ could not have been known by this physician. My vote would be document this ‘remembrance’ even if suspicion is generated in retrospect.