When physicians pick up a chart in the emergency department and see that the chief complaint is low back pain, most have a similar reaction: not another lumbosacral sprain, not another drug-seeker, or not another patient nothing can be done for. Most often, the cause of the low back pain is benign, and many physicians feel ill-equipped with the tools needed to help these patients in any significant way.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 01 – January 2017For whatever reason, there’s a tendency to be nonchalant and complacent about low back pain. That is odd because if you compare the 90 percent of low back pain comprising benign causes to chest pain, it’s not very different. Only about 10 percent to 15 percent of chest pain presentations to the emergency department turn out to be serious. Yet when it comes to patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain, we’re keenly alert about ruling out myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, etc. There are five emergent pathologies that must be considered in every patient who presents with low back pain: infection (osteomyelitis, discitis, spinal epidural abscess), fracture (traumatic or pathologic), disc herniation with cord compression, spinal metastasis with cord compression, and vascular catastrophes (ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm [AAA], retroperitoneal bleed, spinal epidural hematoma). Some of these serious causes of low back pain are easy to miss, and more often than not, they are only diagnosed on the second, third or even fourth visit to the emergency department. So physicians need to approach all low back pain patients with a high degree of scrutiny, especially on repeat visits to the emergency department.

Pertinent Positives and Negatives in Clinical Assessment

With these five causes in mind, I ask patients about risk factors for infection such as IV drug use, spinal interventions, recent infections (eg, endocarditis, which tends to seed to the spine), any cancer history no matter how remote, trauma, or coagulopathy/anticoagulant use. Then I ask about specific symptoms of cord compression and cauda equina syndrome: saddle paresthesias (does it feel different than usual when the patient wipes after a bowel movement?), erectile dysfunction, progressive bilateral leg weakness or numbness, difficulty urinating or urinary retention, and fecal incontinence. Other red flags include constant, unrelenting severe pain that is worse on lying down, which is a red flag for infection or cancer of the spine.

On physical examination, one pearl can be garnered from simply observing the patient’s posture. Patients with a known history of herniated disc and sciatica usually avoid a flexed posture as this places pressure on the nerve roots. However, if they have cauda equina syndrome or cord compression, they tend to favor a flexed posture in order to allow more room for the spinal cord in the spinal canal. This is similar to the classic posture of spinal stenosis patients, who tend to lean on their shopping carts in the grocery store. Tenderness on percussion of the spinous processes, an underutilized physical examination maneuver, is a red flag for infection and fracture.

Cognitive Forcing Strategies for Low Back Pain Presentations

I find cognitive forcing strategies helpful in picking up serious causes of low back pain. In addition to the classic cognitive forcing strategy, “if you’re thinking renal colic, think leaking AAA,” I use, “if you’re thinking pyelonephritis, think spinal epidural abscess,” and “known cancer + new back pain = spinal metastases until proven otherwise.”

Cauda Equina Syndrome Is a Clinical Diagnosis, Not a Radiographic One

It is vital to understand that cauda equina syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, not a radiographic one, and that it can have an acute as well as chronic onset, with one in 1,000 patients with sciatica developing cauda equina syndrome. The diagnostic criteria are the presence of both:

- Urinary retention and/or rectal dysfunction and/or sexual dysfunction and

- Saddle or anal anesthesia or hypesthesia

Therefore, it is imperative that any patient with low back pain and neurological findings receive careful testing for saddle anesthesia, realizing that changes may be subtle and subjective; a digital rectal exam testing for tone and sensation; and a post-void residual measurement. While bladder scanners can give you a rough estimate of bladder volume, they are unreliable, and a bladder catheter measuring the urine output for 30 minutes after insertion is often recommended. A post-void residual of >100 mL should raise the suspicion for cauda equina syndrome in a patient without a history of urinary retention from another cause.

If Thinking Pyelonephritis, Ask Yourself, “Could This Be Spinal Epidural Abscess?”

Spinal epidural abscess should be suspected in all patients with:

- Back pain or neurological deficits and fever, or

- Back pain in an immune-compromised patient, or

- A recent spinal procedure and either of the above.

While diabetes, IV drug use, indwelling catheters, spinal interventions, infections elsewhere (especially skin), immune suppression, and repeat ED visits are all important risk factors for spinal epidural abscess, many patients do not have any risk factors, and the classic triad of fever, back pain, and neurologic deficit is present in only 13 percent of patients.1 Spinal epidural abscess is often missed on first ED visit. Fever is present in only 66 percent of patients, and neurologic deficits start very subtly.2

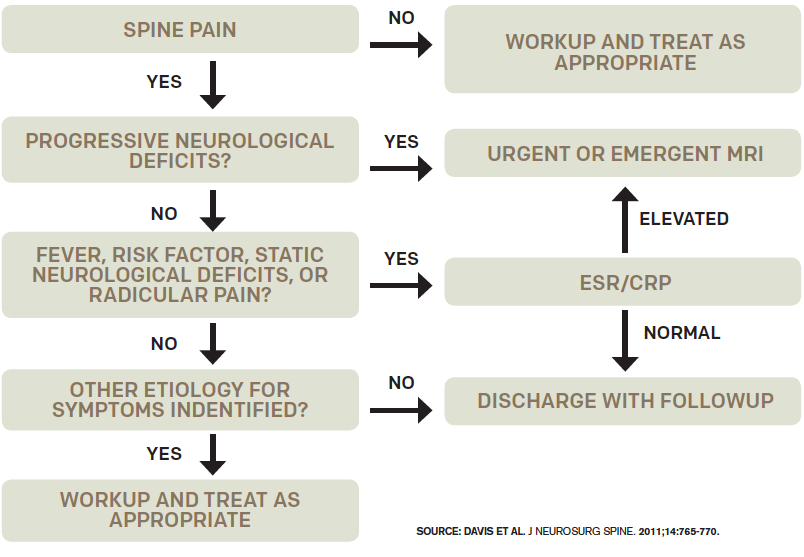

Figure 1: Decision guideline for diagnosing spinal epidural abscess.

C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may help in deciding whether to pursue an MRI, depending on the clinical suspicion for epidural abscess (see Figure 1). In one study, 98 percent of patients with epidural abscess had an ESR >20.3 If suspicion is low after the history and physical, low ESR and CRP levels support not doing an MRI, and discharging the patient home with close follow-up is appropriate. ESR is also helpful for predicing prognosis in patients with spinal metastasis. If there is a high index of suspicion for cord compression, an MRI is indicated regardless of CRP or ESR. See Figure 2 for an algorithm for managing non-traumatic back pain.

Figure 2. Algorithm for management of nontraumatic back pain.

Solid lines indicate usual care; dotted lines indicate options based on case-by-case clinical judgment.

Credit: Reprinted with permission from Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:148-153.

One of the most common pitfalls in working up the patient suspected of spinal infection, and a good example of the cognitive bias of premature closure, is finding osteomyelitis on CT scan and stopping there. CT cannot rule out a concomitant epidural abscess, which requires urgent surgical decompression, because it does not show the epidural space, spinal cord, or spinal nerves adequately. Another common imaging pitfall is not imaging the entire spine when epidural abscess is being considered. Remember, if the suspicion is epidural abscess or spinal metastasis, the entire spine must be imaged by MRI.

So next time you see patients with low back pain in the emergency department on their third visit for the same illness, consider the big five diagnoses; employ cognitive forcing strategies; ask about risk factors and red flags; assess the posture of sciatica patients; perform a careful exam for saddle anesthesia; consider a post-void residual, CRP, and/or ESR; and obtain an MRI of the entire spine for suspected spinal infection or spinal metastases. Your patients will thank you, and you may stay out of court.

A special thanks to Dr. Walter Himmel and Dr. Brian Steinhart for their participation in the EM Cases podcast from which this article is based.

Dr. Helman is an emergency physician at North York General Hospital in Toronto. He is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Division of Emergency Medicine, and the education innovation lead at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. He is the founder and host of Emergency Medicine Cases podcast and website.

Dr. Helman is an emergency physician at North York General Hospital in Toronto. He is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Division of Emergency Medicine, and the education innovation lead at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. He is the founder and host of Emergency Medicine Cases podcast and website.

References

- Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, et al. The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):285-291.

- Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23(4):175-204.

- Davis DP, Salazar A, Chan TC, et al. Prospective evaluation of a clinical decision guideline to diagnose spinal epidural abscess in patients who present to the emergency department with spine pain. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14(6):765-770.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “Low Back Pain Emergencies Could Signal Neurological Injuries”

March 1, 2020

Steven Shroyer MD FACEPNice review Dr Hellman. If I could add, more recent literature including the two your referenced by D Davis 2004 and 2011 warn not to wait for back pain and fever, since this will miss the majority of spinal infections. Both of these articles indicate only 24% (2004 JEM) and 7% (2011 JNS)of spinal infections had fever >= 100.4 degrees F. Also these two articles indicate 100% of spinal infections had one or more risk factors–much more sensitive than fever. Thanks for the article. Steve

January 11, 2025

Chijioke OtikpaWonderful document! But discussing non specific low back pain management while carefully avoiding any mention of physical therapy is WILD!

So there’s no PT referral plan at any point?