Dr. DuCanto, an anesthesiologist with a unique passion for the airway, created a vomiting mannequin on which to practice intubation in the face of massive fluids. Dr. Levitan has been lucky enough to teach with him and Dr. Chow. Dr. DuCanto and Dr. Chow have thought about vomit in the airway more than anyone else on the planet.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 05 – May 2017

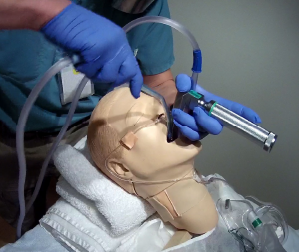

Figure 3: Two suction catheters during laryngoscopy. The operator has stabilized the first catheter in the hypopharynx with the left hand (with same hand holding the laryngoscope). The second catheter is in the operator’s right hand, being used for additional suctioning, immediately before placing the tube.

PHOTOS: Richard Levitan

The following tips and tricks for managing fluids in the airway are a combination of Dr. Levitan’s suggestions and techniques from Dr. DuCanto and Dr. Chow.

- Preoxygenate as upright as possible. This will give patients the longest safe apnea time, and is especially critical in obese patients. Do this with a standard nasal cannula and a mask (either continuous positive airway pressure therapy, bag-valve mask, or non-rebreather mask). Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is essential in many obese patients and those with fluid-filled alveoli. Single-use disposable PEEP valves should be on every bag-valve mask in the ED (see Figure 1).

- Decompress the gastrointestinal bleeders and bowel-obstructed patients with an nasogastric (NG) tube before induction. The volume of fluid that can come up in these instances can be catastrophic. I prefer to remove the NG tube (suctioning as it is withdrawn) just prior to laryngoscopy (but after induction) because I don’t want to work around it during intubation. In situations where the fluids are just not stopping, I would leave it in during the intubation and work around the NG.

- Positioning is critical during intubation. Head elevation is best for opening alveoli, especially in obese patients. In fluid-filled airways, you want the fluids to go posteriorly into the esophagus. Also, as fluid fills the esophagus when muscular tone is lost from rapid-sequence intubation (RSI) or unconsciousness, you want gravity to keep it from going into the pharynx. In the sickest of these patients, an upright intubation, either facing the patient or the operator standing on the bed or stool, may be best.

- Have two suction setups with the largest suction catheters available. Test them before induction. It’s amazing how complicated the suction setups seem in the midst of chaos; getting the right tubing connected to the correct ports on the canister can be a challenge. This should be done before starting the procedure. A standardized location for the suction is best as it can be difficult to find and is easily knocked to the ground when things become chaotic. We suggest that they be tucked under the right shoulder or corner of the bed. Large-bore rigid suction catheters are available from at least two medical device companies and can be a tremendous upgrade in the handling of fluids. The two principle products in the United States are the Big Yank by ConMed and the DuCanto catheter by SSCOR, Inc. (Dr. DuCanto, invented this device, and he receives royalties on this product.) Tracheal tubes can also be used as suction devices when connected to suction tubing either with a meconium aspirator or by flipping the endotracheal tube connector around on a 7.0 to 8.0 mm tracheal tube (see Figure 2). Another option is to use a meconium aspirator connected to an adult-sized tracheal tube.1

- Suction before blade insertion. It makes no sense to immerse a video device into the fluid pool. Even a direct laryngoscope is compromised if the light is buried in the fluid. The rigid suction catheter can be used to assist control of mouth opening and tongue control during initial laryngoscope blade insertion to improve the efficiency of laryngoscopy and potentially improve success at first-pass laryngoscopy. Dr. DuCanto and Dr. Chow advocate using the rigid suction catheter as a means of opening the mouth, manipulating the tongue, and draining fluids to progressively expose landmarks.

- After suctioning with one Yankauer or other device, place this first suction catheter to the left of the laryngoscope blade into the hypopharynx (below the larynx), where it can continue to drain fluids from the esophagus while reducing its potential to evacuate supplemental oxygen supplied via the nasal cannula. In this position, the rigid suction catheter will be held by the laryngoscope blade (medially) and the patient’s pharynx (laterally) (see Figure 3). Some Yankauer catheters require a vent hole to be occluded in order to generate suction; tape up the vent hole if needed to provide continuous suction. (This is one of design advantages of Dr. DuCanto’s catheter—there is no vent hole.)

- Use a second suction device to suction the hypopharynx (with the right hand) immediately before placing the tracheal tube.

- Pay particular attention to progressive visualization of landmarks in the setting of massive fluids. Find the palatal arch, the uvula, and the horizontal edge of the epiglottis, and work the suction tip deeper until the posterior cartilages and glottic opening are seen (see Figure 4).

- Check the cuff after placement. Proper inflation and seal are especially important. Verify end-tidal CO2, check the post-intubation X-ray, and make sure to return the NG tube to suction.

Some institutions have subglottic suction tubes. These tubes have a thick sidewall (about a millimeter thicker than a standard tube) and port that is just above the cuff. This allows suctioning of fluids below the cords but above the cuff of the tube. These tubes markedly reduce the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. They are made by several different manufacturers and would be a good idea in situations where blood or secretions are prodigious. I am not sure it would have any benefit in situations with vomitus, depending on the particulate size, as the subglottic suction hole is relatively small.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

One Response to “How to Manage Fluids in Emergency Airway Procedures”

May 18, 2017

Kyle StricklandAre the authors advocating Preoxygenation of a spontaneously breathing patient with a BVM? I have read that this is superior to NRB but hear many arguments against the use of BVM in spontaneously breathing patients. thanks