Explore This Issue

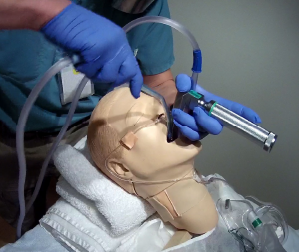

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 05 – May 2017Figure 1: PEEP valve attached to bag-valve mask. Notice nasal cannula under the mask, as well as hand positioning of operators. The first operator holding the bag has his hand under the bag for balance. The second operator is holding the mask tightly against the patient’s face while actively moving the mandible forward at the same time. This patient positioning and two-operator coordination are far superior to trying this flat and pushing the mask down onto the mandible. PHOTOS: Richard Levitan

It has long been assumed in emergency airway management that the fundamental priorities are oxygenation and ventilation. Apart from instances of severe acidosis with compensatory respiratory alkalosis, ventilation is rarely as time critical as oxygenation. Desaturation and severe hypoxemia kills in seconds to minutes; the lack of ventilation causes a buildup of carbon dioxide and eventually acidosis, but it is only critical when patients start out severely acidotic (eg, diabetic ketoacidosis, salicylate overdose, acute renal failure, rhabdomyolysis, etc.).

Next to oxygenation, the priorities of emergency airway management are the management of fluids and the prevention of regurgitation and aspiration. Fluid regurgitation and vomiting has been underaddressed as a life threat in emergency airways.

Every seasoned clinician has encountered clinical situations where fluids impeded laryngoscopy and ventilation. Fluids are, in fact, the enemy of everything in the airway. They make direct and video laryngoscopy more challenging because they obscure landmarks. Look-around-the-curve video devices fail when fluid splatters across the optical element. Endoscopes are particularly useless when there is significant fluid in the airway as it is nearly impossible to keep the lens clean and discern an open pathway.

Figure 2: Flipping over the connector of a 7.0–8.0 mm tracheal tube, allowing it to be connected to standard suction tubing PHOTOS: Richard Levitan

The most serious threat of fluids in the airway is not with laryngoscopy but rather with oxygenation. Apneic oxygenation, bag-mask ventilation, and rescue devices like the laryngeal mask airway and King LT all function poorly, if at all, when there is a high volume of fluid in the airway. In fact, there is only one airway management technique that can overcome massive fluids in the upper airway: cutting the neck. Cricothyrotomy, with a cuffed tube in the trachea, separates the airway from the shared aerodigestive tract through which all other means of oxygenation are dependent upon. When fluids are uncontrollable, it may be the only option and must be done quickly.

Dr. DuCanto, an anesthesiologist with a unique passion for the airway, created a vomiting mannequin on which to practice intubation in the face of massive fluids. Dr. Levitan has been lucky enough to teach with him and Dr. Chow. Dr. DuCanto and Dr. Chow have thought about vomit in the airway more than anyone else on the planet.

Figure 3: Two suction catheters during laryngoscopy. The operator has stabilized the first catheter in the hypopharynx with the left hand (with same hand holding the laryngoscope). The second catheter is in the operator’s right hand, being used for additional suctioning, immediately before placing the tube.

PHOTOS: Richard Levitan

The following tips and tricks for managing fluids in the airway are a combination of Dr. Levitan’s suggestions and techniques from Dr. DuCanto and Dr. Chow.

- Preoxygenate as upright as possible. This will give patients the longest safe apnea time, and is especially critical in obese patients. Do this with a standard nasal cannula and a mask (either continuous positive airway pressure therapy, bag-valve mask, or non-rebreather mask). Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is essential in many obese patients and those with fluid-filled alveoli. Single-use disposable PEEP valves should be on every bag-valve mask in the ED (see Figure 1).

- Decompress the gastrointestinal bleeders and bowel-obstructed patients with an nasogastric (NG) tube before induction. The volume of fluid that can come up in these instances can be catastrophic. I prefer to remove the NG tube (suctioning as it is withdrawn) just prior to laryngoscopy (but after induction) because I don’t want to work around it during intubation. In situations where the fluids are just not stopping, I would leave it in during the intubation and work around the NG.

- Positioning is critical during intubation. Head elevation is best for opening alveoli, especially in obese patients. In fluid-filled airways, you want the fluids to go posteriorly into the esophagus. Also, as fluid fills the esophagus when muscular tone is lost from rapid-sequence intubation (RSI) or unconsciousness, you want gravity to keep it from going into the pharynx. In the sickest of these patients, an upright intubation, either facing the patient or the operator standing on the bed or stool, may be best.

- Have two suction setups with the largest suction catheters available. Test them before induction. It’s amazing how complicated the suction setups seem in the midst of chaos; getting the right tubing connected to the correct ports on the canister can be a challenge. This should be done before starting the procedure. A standardized location for the suction is best as it can be difficult to find and is easily knocked to the ground when things become chaotic. We suggest that they be tucked under the right shoulder or corner of the bed. Large-bore rigid suction catheters are available from at least two medical device companies and can be a tremendous upgrade in the handling of fluids. The two principle products in the United States are the Big Yank by ConMed and the DuCanto catheter by SSCOR, Inc. (Dr. DuCanto, invented this device, and he receives royalties on this product.) Tracheal tubes can also be used as suction devices when connected to suction tubing either with a meconium aspirator or by flipping the endotracheal tube connector around on a 7.0 to 8.0 mm tracheal tube (see Figure 2). Another option is to use a meconium aspirator connected to an adult-sized tracheal tube.1

- Suction before blade insertion. It makes no sense to immerse a video device into the fluid pool. Even a direct laryngoscope is compromised if the light is buried in the fluid. The rigid suction catheter can be used to assist control of mouth opening and tongue control during initial laryngoscope blade insertion to improve the efficiency of laryngoscopy and potentially improve success at first-pass laryngoscopy. Dr. DuCanto and Dr. Chow advocate using the rigid suction catheter as a means of opening the mouth, manipulating the tongue, and draining fluids to progressively expose landmarks.

- After suctioning with one Yankauer or other device, place this first suction catheter to the left of the laryngoscope blade into the hypopharynx (below the larynx), where it can continue to drain fluids from the esophagus while reducing its potential to evacuate supplemental oxygen supplied via the nasal cannula. In this position, the rigid suction catheter will be held by the laryngoscope blade (medially) and the patient’s pharynx (laterally) (see Figure 3). Some Yankauer catheters require a vent hole to be occluded in order to generate suction; tape up the vent hole if needed to provide continuous suction. (This is one of design advantages of Dr. DuCanto’s catheter—there is no vent hole.)

- Use a second suction device to suction the hypopharynx (with the right hand) immediately before placing the tracheal tube.

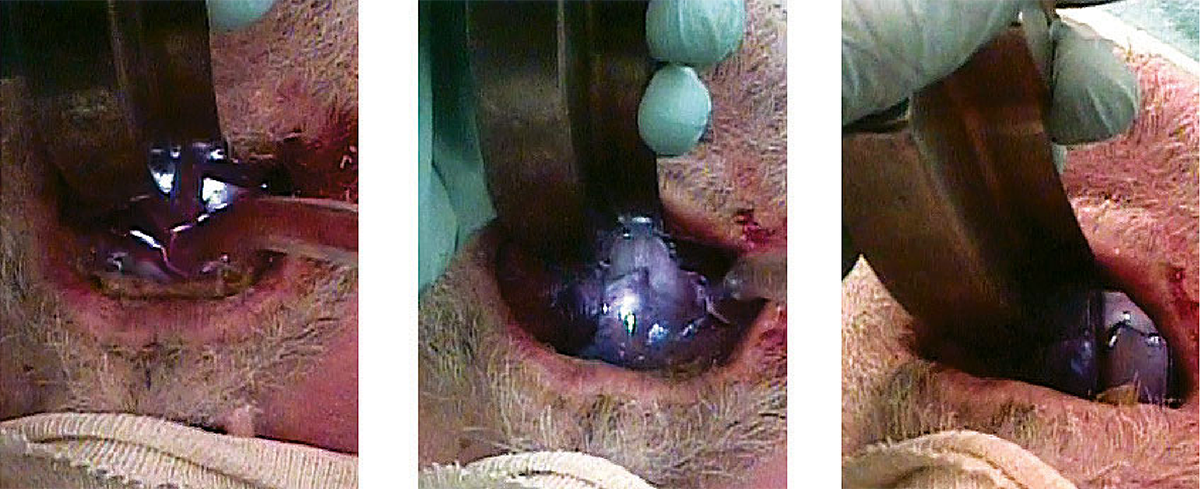

- Pay particular attention to progressive visualization of landmarks in the setting of massive fluids. Find the palatal arch, the uvula, and the horizontal edge of the epiglottis, and work the suction tip deeper until the posterior cartilages and glottic opening are seen (see Figure 4).

- Check the cuff after placement. Proper inflation and seal are especially important. Verify end-tidal CO2, check the post-intubation X-ray, and make sure to return the NG tube to suction.

Some institutions have subglottic suction tubes. These tubes have a thick sidewall (about a millimeter thicker than a standard tube) and port that is just above the cuff. This allows suctioning of fluids below the cords but above the cuff of the tube. These tubes markedly reduce the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. They are made by several different manufacturers and would be a good idea in situations where blood or secretions are prodigious. I am not sure it would have any benefit in situations with vomitus, depending on the particulate size, as the subglottic suction hole is relatively small.

(click for larger image)

Figure 4: Image sequence for landmark visualization in the setting of massive fluids.

PHOTOS: Richard Levitan

Two final points: Have surgical airway tools ready. If intubation from above is impossible, the only way to oxygenate your patient may be a cricothyrotomy. It should be at the bedside and should be discussed with everyone on the team. This lowers the cognitive threshold for making the decision. Most surgical airways fail not because of technical difficulty but because they are initiated on dead patients. If intubation from above is unsuccessful, cut before the patient codes.

Lastly, gown up and use eye protection. In the words of Mike Tyson, “Everyone has a plan, until they get hit in the face!”

Dr. Levitan is an adjunct professor of emergency medicine at Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, New Hampshire.

Dr. Chow is assistant professor in emergency medicine/family practice at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Thunder Bay.

Dr. DuCanto is a staff anesthesiologist and director of simulation center at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee.

Reference

- Weingart S. A novel set-up to allow suctioning during direct endotracheal and fiberoptic intubation. EMCrit website. Accessed on April 25, 2017.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “How to Manage Fluids in Emergency Airway Procedures”

May 18, 2017

Kyle StricklandAre the authors advocating Preoxygenation of a spontaneously breathing patient with a BVM? I have read that this is superior to NRB but hear many arguments against the use of BVM in spontaneously breathing patients. thanks