The Miriam Hospital is a 247-bed community hospital affiliated with the Warren Alpert School Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. The emergency department sees 68,000 visits annually in its 61 treatment spaces, which include 21 lounge chairs for vertical flow. The emergency department has had a long reputation for efficiency and service quality. The ED physicians and staff have always been proud of their performance metrics and empty waiting room. However, after crossing the 60,000-visit volume band, the department began to falter operationally, and its wait times increased. The new normal included an often full waiting room. The emergency department, which effectively operates as a geriatric emergency department (more than 30 percent of its patients being older than age 65), often found itself with Emergency Severity Index (ESI) 2 patients being placed back in the waiting room, a situation that did not please staff.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 02 – February 2017Hospital President Arthur Sampson and ED Medical Director Gary Bubly, MD, decided to undergo a comprehensive ED operations assessment conducted by an objective third party. The assessment identified opportunities for improvement. The leaders were committed to improving the emergency department but needed a road map of where to start. After the assessment, Dr. Bubly, along with his associate director, Ilse Jenouri, MD, and his nursing counterparts, Denise Brennan, nurse director of emergency services, and Bob Boss, clinical manager, decided to trial a change package with a set of complementary improvements that would commence simultaneously.

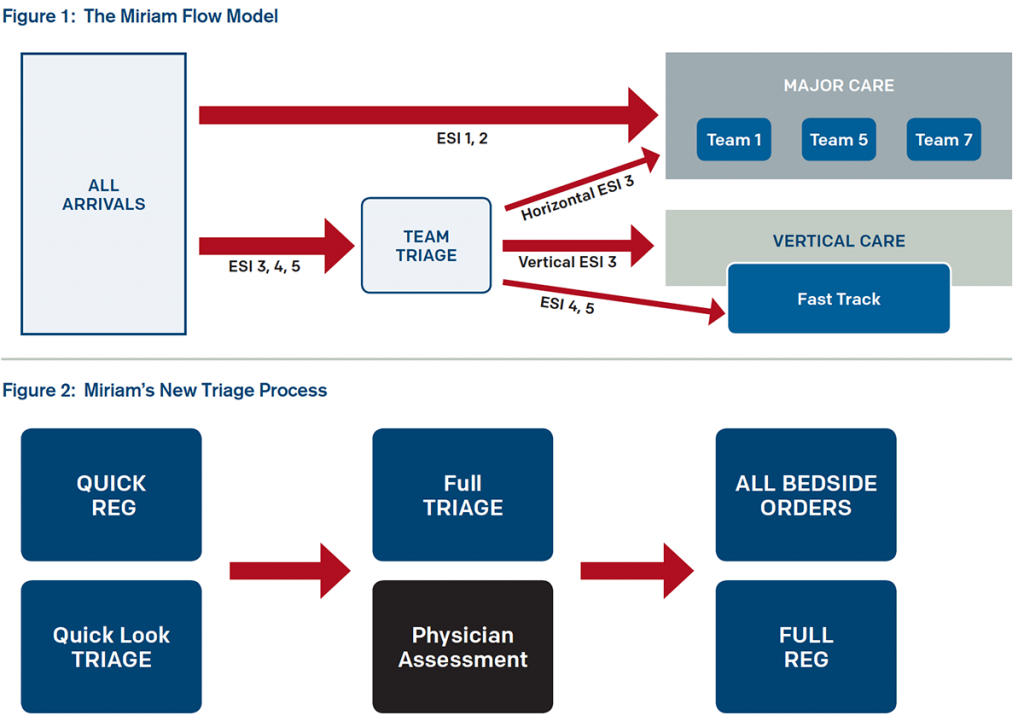

Using data, interviews, and observation, the ED operations experts argued that the emergency department had the space and personnel to manage the volumes. Their assessment revealed that intake was cumbersome, with many delays as most steps were conducted in series. Further, though the Miriam emergency department had just begun patient streaming and treating patients in chairs, there was no improvement in wait times because the streaming was not decisive and most geographic zones were mixed-acuity service lines. This made it hard to move low-acuity patients through the system quickly. Other patient flow and housekeeping issues were identified. Using data the leadership team developed, the emergency department implemented the flow model in Figure 1 using the major care/minor care concept used in Great Britain.

The leadership team cleverly dubbed the change package “The Miriam: FAST FORWARD>>.” It connotes the overarching theme of trying to regain lost efficiencies. The changes included:

- Team triage, which made the most of the physical layout.

- A patient flow coordinator (PFC) to monitor flow into the department and, where possible, load-level the various zones.

- Low-acuity patient streams (fast track and vertical flow), which place lower-acuity patients into cohorts depending on resource need.

- A housekeeping improvement initiative to rectify the problem of empty but dirty rooms.

The leadership crafted a new triage process that has many steps now happening in parallel (see Figure 2).

The physician contact is now very early in the ED encounter, and lab testing is initiated at triage. The physician can decide which zone is most appropriate for the patient, but the PFC assigns the room.

The PFC is a role that is growing in popularity, especially in emergency departments seeing more than 50,000 visits per year. The PFC manages incoming ambulances and has the 30,000-foot view of the workload in each area. As emergency departments get busy with increased numbers of geographic zones, an overview is lost unless someone is dedicated to monitoring and managing flow. This role works best when it is in addition to the charge nurse role, which was becoming unmanageable in terms of scope of duties. The charge nurse and PFC work as a team and are in constant communication (cellphones with speed dial) to share information for flow management. The charge nurse now focuses on one area with attention to outflow, admissions, and discharges. The charge nurse can inform the PFC as to workload in the back, the status of patients, and which patient is likely to be moving next. Together, they manage overall patient flow.

Patients were grouped according to acuity and resources needed. This allowed for the realization of new efficiencies, and many fast-track patients were turned around in under an hour! Housekeeping fine-tuned its processes to decrease the downtime of most rooms.

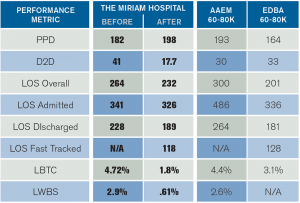

The results were astonishing and unequivocal. After four rapid-cycle tests of change, the leaders and stakeholders had ironed out the bugs and were ready to turn on their new ED processes for good. Compare their results where they were underperforming relative to the Academy of Administrators in Academic Emergency Medicine and Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance cohorts before and are now top performers (see Table 1).

(click for larger image)

Table 1: Miriam’s Performance Before and After Intervention

Compared to Benchmark Data

Definitions: PPD, patients per day; D2D, door-to-doctor time; LOS, length of stay; LBTC, left before treatment complete; LWBS, left without being seen; AAAEM, Academy of Administrators in Academic Emergency Medicine; EDBA, Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance

There are some take-home messages that are important to all ED leaders and managers reading this story. You will need to change your processes as your volumes grow. In particular, as you jump a volume band, what has worked before no longer works at the increased volumes. Parallel processing, patient streams that segment patients according to the time and resources they will need, and pushing the provider to the front of the encounter are all forward-thinking ED flow strategies. For The Miriam Hospital emergency department, this change package helped get its mojo back! Once again, the ED members are top performers in their system. From now on, they will continue moving their patients fast forward and achieving higher levels of performance and great success!

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Miriam Hospital’s FAST FORWARD>> Program Regains Lost Patient Flow Efficiencies”