The year 2020 highlighted our flaws. Unprepared, we faced a pandemic that has now killed more than 540,000 people in the United States. Because of quarantines, a captive audience witnessed horrible acts of police brutality displayed on television and portable screens all across the nation. Systemic racism was highlighted from our legal system to our medical institutions. Outrage led to protests, and protests led to conversations.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 04 – April 2021So in 2021, after all of our talking, what do we do now? Health care disparities in medicine have long been recognized and discussed. We know that minorities are at increased risk of death from almost every disease process. The major cognitive shift that 2020 helped many see is that much of these racial disparities are social and not biological. How do we change from race-based medicine to race-conscious medicine?

A recent article in Lancet about race-based care highlighted the fact that race is often blindly used as a biological proxy in how we characterize, diagnose, and administer care to all of our patients.1 However, it would be naive to think that race does not impact the care administered to patients every day. Some are aware of race but claim to be “color-blind”—to imply that race does not affect one’s decisions if the individual does not acknowledge race. Color blindness leads to systemic racism blindness. If you cannot see race, how can you see the structures and policies created to discriminate because of race?

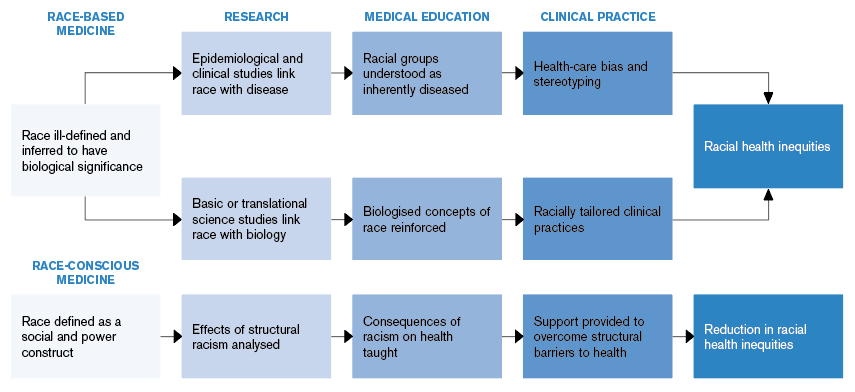

One way to incorporate the social effects of race on medicine is to be race-conscious (see Figure 1). This means acknowledging race not as a biological risk factor but as a social risk factor that promotes policies and procedures that discriminate against minorities.

(click for larger image) Figure 1: How Race-Based Medicine Leads to Racial Health Inequities

Source: Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1125-1128. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

But how exactly can we do that? Education—or rather the re-education—of students, residents, and attendings on this subject is critical. Understanding the history of race in medicine that translated into race as a proxy for disease can highlight medicine’s implicit biases. This acknowledgment could cause a paradigm shift in medical education that teaches race as a proxy for medical discrimination that leads to racial health disparities. Doing this offers us something positive and substantive to do: It helps us better identify where our focus belongs in our work to improve outcomes.

Along with this shift in education, new policies and procedures are necessary to overcome existing structural barriers to care in realms of research and clinical practice. A few peer-reviewed journals are actively taking this important step. The New England Journal of Medicine published an article in 2020 called “Hidden in Plain Sight—Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms.”2 As the authors wrote, “To be clear, we do not believe that physicians should ignore race. Doing so would blind us to the ways in which race and racism structure our society. However, when clinicians insert race into their tools, they risk interpreting racial disparities as immutable facts rather than as injustices that require intervention. Researchers and clinicians must distinguish between the use of race in descriptive statistics, where it plays a vital role in epidemiologic analyses, and in prescriptive clinical guidelines, where it can exacerbate inequities.”

The journal Circulation published “Call to Action: Structural Racism as a Fundamental Driver of Health Disparities: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association” in November 2020.3 As the authors wrote, “The American Heart Association must look internally to correct its own shortcomings and advance antiracist policies and practices regarding science, public and professional education, and advocacy. With this advisory, the American Heart Association declares its unequivocal support of antiracist principles.”

These peer-reviewed journals’ acknowledgement of structural racism gives support to begin dismantling racist policies and practices that contribute to health disparities.

Structural racism is a thread in the fabric of medical care in the United States. Moving from race-based to race-conscious care is using the same thread but creating new practice patterns that truly reflect and affect everyone equitably.

Dr. Baker is chair of emergency medicine at Chestnut Hill Hospital at Tower Health in Philadelphia.

Dr. Baker is chair of emergency medicine at Chestnut Hill Hospital at Tower Health in Philadelphia.

References

- Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1125-1128.

- Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight—reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874-882.

- Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454-e468.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Moving from Race-Based to Race-Conscious Care”