The Case

A 57-year-old man is brought in by family in a private vehicle after a “heroin overdose.” The patient had just gotten out of rehab and was doing well until that day, when the family found him blue and unresponsive. The patient regains spontaneous respirations and normal oxygenation after two doses of naloxone in the ED. He is clinically stable after several hours of observation in the ED, and you think he is ready for discharge. What do you have available in your ED to prevent a recurrent overdose or overdose death?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 03 – March 2016Given the high prevalence of opioid dependency and abuse among emergency department patients and the increasing frequency of overdose-related ED visits, emergency physicians have an opportunity to prevent opioid overdose deaths.1–3 ED naloxone distribution is a simple, cost-effective way to provide a lifesaving intervention.4–7 In August 2015, the ACEP Trauma & Injury Prevention Section organized a webinar on practical considerations when starting a program. Key considerations every ED naloxone program must consider include program implementation and utilization, policies and regulations, means of distribution, cost, and patient education.

Program Implementation and Utilization

Primary factors influencing program utilization include knowledge of literature-based evidence; policies and laws; ED/hospital support, policies, and procedures; professional organizations’ policies and guidelines; and cost/payment mechanisms. Program incorporation into normal work routines can diminish utilization barriers and facilitate support. Policies, procedures, and expectations should be easy to understand and readily accessible.

Patient barriers to naloxone—including stigma, mistrust of medical providers, fear of legal consequences for possession or use, and fear of withdrawal after receiving naloxone—should be addressed. Building patient trust and soliciting feedback will improve program acceptability and quality.

Prominent provider barriers include negative attitudes toward addiction, lack of knowledge about naloxone, and lack of clarity about who should receive naloxone. We recommend naloxone for patients who use heroin, exceed 100 mg morphine equivalents daily, have opioid abuse/dependency, or have had an opioid overdose. Staff training, program monitoring, and staff feedback should be data driven and provided on a regular basis.

Policies and Regulations

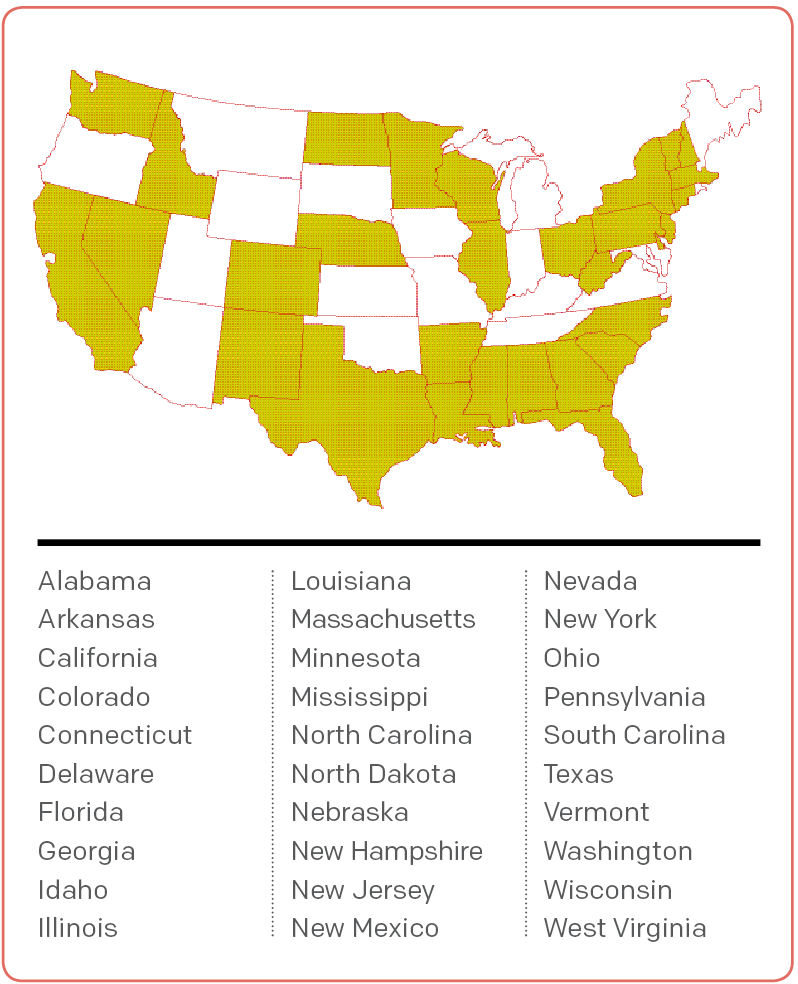

There is significant regulatory variability among states.8 Thirty-seven states have successfully amended legal regulations to eliminate legal barriers to naloxone distribution.9,10 Access to naloxone is the main barrier faced by patients and programs, as there are few providers willing to prescribe or distribute naloxone. State emergency medical services (EMS) laws also can restrict which first responders can carry naloxone.11 Liability, real or perceived, is also an important barrier for prescribers, pharmacists, and bystanders. Regulatory solutions include third-party prescribing, standing naloxone orders, collaborative practice agreements, pharmacist-as-prescriber policies, Good Samaritan laws, and increasing EMS/first responder access. Information about these types of legislation and what is present in your state can be found at lawatlas.org/query?dataset=laws-regulating-administration-of-naloxone. (See Figure 1, for a map of states that have legislation preventing prescribers from being criminally liable for prescribing, dispensing, or distributing naloxone to laypeople.)

Means of Distribution

Providers can provide naloxone directly to patients, write a prescription, or refer patients to a community organization or pharmacy participating in a collaborative practice agreement. Prescribing is low-impact to the system and can be implemented immediately.

Naloxone is offered in intramuscular (IM) and intranasal (IN) formulations. IM can be delivered in the lateral arm or thigh. IN is given as a spray in each nostril with similar efficacy and safety.12,13

IM naloxone can be dispensed as two single-dose vials, 0.4 mg/mL, with syringe and needles. Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Evzio is a prefilled auto-injector that contains a single dose of naloxone 0.4 mg.14 IN naloxone is prescribed as a 2 mL prefilled luer-lock needleless syringe with an IN mucosal atomizing device.15 The recently FDA-approved Narcan is a preloaded nasal atomization device that delivers a single 4 mg dose. This higher dose is necessary for IN route of delivery and for patients who do not respond to the lower dose (e.g., after fentanyl overdose). With the exception of the preloaded IN device, it is recommended that you prescribe two naloxone doses.

Cost

ED naloxone programs may be funded through your hospital, grants, or local governmental agencies. Public health departments and community-based naloxone programs can also be key allies. Depending on your state, Medicaid may reimburse for the naloxone kit and/or overdose education.

Figure 1. States With Legislation Preventing Prescribers From Being Criminally Liable for Prescribing, Dispensing, or Distributing Naloxone to Laypeople

Source: Law Atlas.

The cost of naloxone ranges by manufacturer (see Table 1). The Evzio auto-injector may also be covered by insurance or Kaléo’s patient assistance program.16 To accurately estimate cost, first estimate need and then select items for your naloxone kits. Take-home naloxone kits are given to patients or their loved ones for out-of-hospital use in case of an overdose and may include educational materials, nasal atomizers or needle and syringes, gloves, face shield, and two doses of naloxone.

Patient Education

Patient education should cover overdose risk factors, avoiding overdose, recognizing and responding to an overdose, and administration of naloxone. A combination of in-person counseling and an educational video or handout is best, if feasible. Family and friends should be included in the training, as they may be administering naloxone in an out-of-hospital overdose.

In-person education by staff or a drug counselor is interactive and can be combined with a referral to treatment. If in-person education is not feasible, video and handout materials are cheaper, portable, and uniform and can be referenced at home. However, they are less personal and less engaging and may miss an opportunity for referral to treatment. PrescribeToPrevent.org has educational materials tailored to different patient populations.17

Back to the Case

Before the patient is discharged, he and his family are counseled on the dangers of heroin use, how to recognize an overdose, and the proper technique for administering naloxone. They are given some written educational materials and a naloxone kit to use if the patient overdoses again.

Conclusion

Emergency physicians treat patients with addiction and opioid overdose every day. Increasing access to naloxone is one strategy ED providers can use to reduce deaths due to opioid overdose. For more information about how to set up a program and to access the full ACEP TIPS webinar report, go to www.acep.org/traumasection.

Dr. Samuels is in the department of emergency medicine at Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr. Hoppe is in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. Dr. Papp is in the department of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Whiteside is in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Raja is in the department of emergency medicine at Boston Medical Center, Boston University School of Medicine. Dr. Bernstein is in the department of emergency medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Rockett IR, Putnam SL, Jia H, et al. Unmet substance abuse treatment need, health services utilization, and cost: a population-based emergency department study. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(2):118-127.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Dwyer K, Walley AY, Langlois BK, et al. Opioid education and nasal naloxone rescue kits in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):381-384.

- Samuels E. Emergency department naloxone distribution: a Rhode Island department of health, recovery community, and emergency department partnership to reduce opioid overdose deaths. R I Med J. 2014;97(10):38-39.

- Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 158(1):1-9.

- Inocencio TJ, Carroll T, et al. The economic burden of opioid-related poisoning in the United States. Pain Med. 2013;14(10):1534-1547.

- Naloxone overdose prevention laws map. Public Health Law Research Web site. Accessed Oct. 15, 2015.

- Legal interventions to reduce overdose mortality: naloxone access and overdose Good Samaritan laws. The Network for Public Health Law Web site. Accessed Oct. 23, 2015.

- Naloxone for community opioid overdose reversal. Public Health Law Research Web site. Accessed Oct. 23, 2015.

- Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons — United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Accessed Sept. 30, 2015.

- Kerr D, Kelly AM, Dietze P, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness and safety of intranasal and intramuscular naloxone for the treatment of suspected heroin overdose. Addiction. 2009;104(12):2067-2074.

- Barton ED, Colwell CB, Wolfe T, et al. Efficacy of intranasal naloxone as a needleless alternative for treatment of opioid overdose in the prehospital setting. J Emerg Med. 2005;29(3):265-271.

- Evzio (naloxone hcl injection) 0.4 mg auto-injector. Evzio Web site. Accessed Sept. 30, 2015.

- Formulations. Prescribe to Prevent Web site. Accessed Sept. 30, 2015.

- Kaléo Cares Patient Assistance Program. Evzio Web site. Accessed Oct. 22, 2015.

- Materials. Prescribe to Prevent Web site. Accessed Sept. 30, 2015.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Naloxone Distribution Strategies Needed in Emergency Departments”

April 3, 2016

Larry A. Bedard, MD FACEPACEP has come a long way since 2010 when a wacko doctor from California-me- introduced resolutions to have naloxone over the counter and recommend EPs prescribe naloxone in the ER.

However, ACEP still has a long way to go. Tp deny our role in the opiod epidemic, while frequently blaming other specialities for the epidemic is the wrong approach.