Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 03 – March 2017Photo: “New born spinal tap” by Bobjgalindo, licensed underCreative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/>.

The Case

An 11-day-old female neonate with a chief complaint of jaundice was brought to the emergency department by her father. Other symptoms included spitting up with feeding and tactile fever. The patient’s birth history was significant for a full-term vaginal delivery to a mother who was group B streptococcus (GBS) positive during delivery. The father stated that his daughter had been very “good” since birth, had been very “calm,” and almost never cried. On physical examination, the neonate appeared toxic, listless, and jaundiced and was actively vomiting. The initial workup in the emergency department included urinalysis, complete blood count (CBC), and chest X-ray, all of which were unremarkable except for total bilirubin of 19 mg/dL.

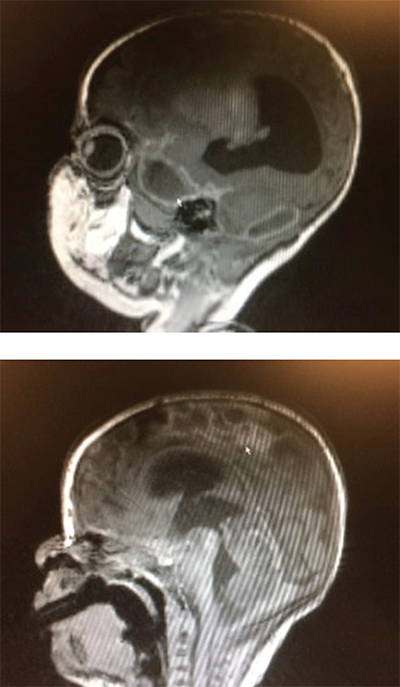

Figure 1 (TOP): Sagittal brain MRI demonstrating a focal area of ischemia (arrow) secondary to meningitis.

Figure 2: Sagittal brain MRI. The ring-encasing lesion (arrow) is demonstrative of subdural empyema in the midbrain secondary to bacterial meningitis.

Photos: Pingching N. Kwan

Given the child’s presentation, age, and birth history, bacterial meningitis was suspected, and a lumbar puncture was suggested. The child’s mother, whom the father was talking to over the phone, initially refused the procedure. However, after extensive discussion about the reasons the procedure was indicated and the low rates of complications associated with the procedure, the child’s mother was convinced, and verbal consent was obtained. The lumbar puncture was performed, and a scant amount (1 mL) of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which appeared to be xanthochromic and turbid, was obtained. The child was listless during the procedure. The fluid was sent for analysis and culture, and the child was started on empiric ampicillin and ceftazidime for suspected bacterial meningitis. The child was admitted to the NICU. CSF analysis and culture confirmed the diagnosis of Escherichia coli meningitis. E. coli was sensitive to cephalosporins.

During her hospital course in the NICU, the child subsequently developed persistent seizures and hydrocephalus. A cranial MRI demonstrated ischemic damage to the brain secondary to meningitis (see Figure 1, arrow) as well as a ring enhancing area in the midbrain (see Figure 2, arrow) representing a subdural empyema. The child was treated with five weeks of IV antibiotics. Unfortunately, her neurological prognosis remains poor.

Discussion

Neonatal meningitis is most commonly caused by vertical transmission of GBS (Streptococcus agalactiae) during delivery, implicated in nearly 50 percent of all cases. Other common pathogens include E. coli and Listeria monocytogenes.1 The cumulative incidence of meningitis is highest in the first month of life and is higher in preterm neonates than term neonates.2 Patients may present with difficulty feeding, apnea, bradycardia, hypotension, irritability, or lethargy. Stupor and irritability are common in late-onset meningitis as are neurological complications. A 2015 study demonstrated that central nervous system complications associated with late-onset GBS meningitis, such as hydrocephalus, epilepsy, subdural empyema, and ischemia, may be underestimated.3

Serious complications can develop rapidly and include cerebral edema, hydrocephalus, hemorrhage, ventriculitis, cerebral infarction, and cerebral abscess formation. Cerebral abscess, such as subdural empyema, can be seen in as many as 13 percent of cases of neonatal meningitis.4 It is a life-threatening condition, causing up to 25 percent of all intracranial infections, with a mortality rate of 4.4–24 percent.5 Signs and symptoms in a neonate include mental status changes, vomiting, and irritability. Treatment should include surgical drainage and triple antibiotic therapy with nafcillin or vancomycin, plus a third-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole. Prognosis is dependent upon the time to surgical intervention as a delay in surgery of 72 hours has been shown to result in 70 percent disability rate as opposed to 10 percent when surgery is performed within 72 hours.6 Complications associated with subdural empyema include seizures, increased intracranial pressure, cerebral infarction, and hydrocephalus.

In the process of diagnosing neonatal meningitis, it is important to keep in mind the possibility of abnormal laboratory studies. A 2006 evaluation of 9,111 neonates with culture-proven bacterial meningitis was performed to determine the correlation between CSF parameters and blood tests. This study demonstrated that 17.3 percent of the 8,312 neonates who had CBC data available had white blood cell (WBC) counts that were within normal parameters (3,000–10,000/mm3) and that the use of peripheral WBC count as a predictor for meningitis had a positive likelihood ratio of 7

Neonatal meningitis is a devastating infection that is often difficult to diagnosis due to physical signs being fairly subtle in the neonate. Therefore, lumbar puncture must be performed promptly to confirm the diagnosis.2 However, obtaining consent for lumbar puncture in the pediatric population can sometimes be problematic. Arguably one of the most difficult scenarios experienced in the emergency department is parents declining consent to procedures that are in the best interest of their child. Research has been pursued to determine the initial reasons behind parental dissent. A qualitative analysis in two hospitals in the United Arab Emirates published in 2012 involving 55 families found that 24 families (44 percent) refused lumbar puncture. The primary reasons for refusal included fear of paralysis as a result of the procedure, pain, perception of the lumbar puncture being unnecessary, and a distrust of motives behind the consent.8

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and ACEP endorse the principle that treating a minor for an emergent condition should not be delayed solely due to difficulties in obtaining consent.9 An approach described in the Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures suggests a discussion on the need for the procedure, the relatively low risk of the procedure, and the reasons parents have for dissent. If discussion fails to convince parents to consent to the procedure, consider notifying the hospital attorneys, as the hospital could pursue protective custody and obtain a court order to perform the procedure.9

Dr. Kwan is an emergency physician with Emergency Medical Management Associates and associate medical director at Garfield Medical Center in Monterey Park, California.

Dr. Kwan is an emergency physician with Emergency Medical Management Associates and associate medical director at Garfield Medical Center in Monterey Park, California.

Mr. Williams is a fourth-year medical student at Western University School of Medicine in Pomona, California.

Mr. Williams is a fourth-year medical student at Western University School of Medicine in Pomona, California.

References

- Klinger G, Chin CN, Beyene J, et al. Predicting the outcome of neonatal bacterial meningitis. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):477-482.

- Smith PB, Garges HP, Cotton CM, et al. Meningitis in preterm neonates: importance of cerebrospinal fluid parameters. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(7):421-426.

- Tibussek D, Sinclair A, Yau I, et al. Late-onset group B streptococcal meningitis has cerebrovascular complications. J Pediatr. 2015;166(5):1187-1192.

- Garges HP, Moody MA, Cotten CM, et al. Neonatal meningitis: what is the correlation among cerebrospinal fluid cultures, blood cultures, and cerebrospinal fluid parameters? Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1094-1100.

- Doan N, Patel M, Nguyen HS, et al. Intracranial subdural empyema mimicking a recurrent chronic subdural hematoma. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;2016(9).

- Agarwal A, Timothy J, Pandit L, et al. A review of subdural empyema and its management. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2007;15(3):149-153.

- Malbon K, Mohan R, Nicholl R. Should a neonate with possible late onset infection always have a lumbar puncture? Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(1):75-76.

- Narchi H, Ghatasheh H, Al Hassani N, et al. Why do some parents refuse consent for lumbar puncture on their child? A qualitative study. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(2):93-98.

- King C, Henretig F eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Neonatal Meningitis Diagnosis Difficult Given Subtle Symptoms of Vomiting, Irritability”

March 9, 2023

Daniel MeressaGood diagnosis with good investigation will end up with good treatment and follow-up