“Whoop, whoop, whoop!” The EMS radio alerts the ED staff to an incoming patient. Minutes later arrives a patient who has a 33 percent chance of being moved to an inpatient bed in about five hours, a 5 percent chance of being moved to the ICU in about three hours, and a chance of being moved onto a medical helicopter or onto a medical examiner’s table.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 05 – May 2019For those emergency physicians working in medical centers that specialize in trauma, burns, acute cardiac intervention, and comprehensive stroke care, those ambulance patients represent the vast majority of patients who pay for such specialty programs and services. For those who don’t like ambulance patients, the future is arriving faster than a medic unit running lights and sirens.

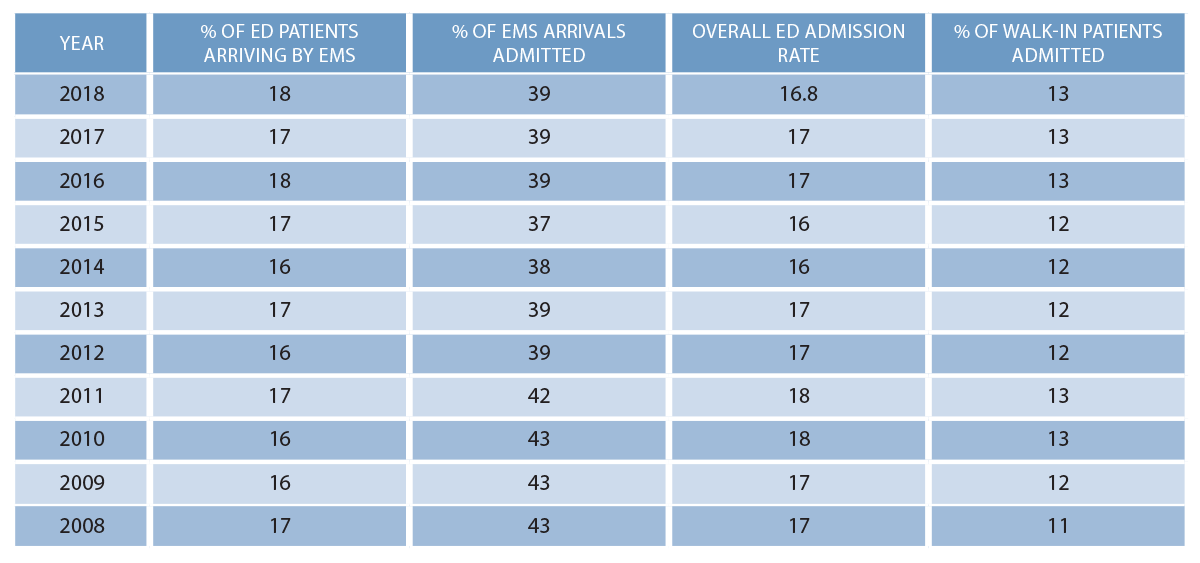

Studying the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) data over the last 10 years, we find that EMS arrivals and admission rates are predictable, and ambulance patients continue to represent higher acuity than those arriving in a private automobile or other conveyance. Table 1 demonstrates that about 39 percent of EMS-arriving patients are admitted. Patients arriving by other means have a significantly lower admission rate of about 12.5 percent.

CMS Launches New Payment Model

On Feb. 14, 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced a new payment model for unscheduled care responders that pays for care that does not include transportation to the hospital.1 The proposed Emergency Triage, Treat, and Transport (ET3) Model will pay for care provided out of hospital, either in person or through telehealth processes. It also pays EMS responders to transport patients by ambulance to alternative out-of-hospital care sites, including urgent care or a primary care provider.

The model’s announced goal is to end the incentives for first responders to transport patients to the emergency department. The program is being introduced by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation as a method to improve the quality of care for unscheduled health events and is targeted to save the health care system $1 billion in avoidable ED costs. CMS believes 19 percent of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries could be treated at home or in another cheaper facility for their emergency needs. CMS also hopes Medicaid managed care plans and private payers will take an interest in the voluntary model.

Program rules have yet to be written, and it may take six or more months until applicants for the model are recruited. However, EMS providers selected to participate will have options in how they wish to structure the on-site element. Options will include a telehealth-heavy model in which a physician or advanced practice provider provides care on-site or remotely. The fact sheet says the demonstration will last five years.

The bottom line? There are evolving models of care that feature alternate providers paid to deliver a variety of services outside of the traditional model of emergency care delivered in the emergency department.

How Will It Affect Your Emergency Department?

The EDBA data over the past 15 years find that EMS arrival and admission rates are very stable and that patients arriving by ambulance continue to represent higher acuity. At the same time, many emergency departments have been unable to open sufficient space to provide care for all arriving patients, and some hospitals have developed processes for diverting ambulances. This issue was recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in studies years ago but has not been resolved.2 This winter, the media highlighted the ongoing danger of ambulance diversion.3,4

Patients who are high-frequency emergency system users can be identified by case managers, hospitals, emergency departments, or the EMS system. Is the use of out-of-hospital health services a mark of quality for these individuals? There is still a legal issue to address in which a 911 call can be linked to an EMTALA responsibility and the mandate for a medical screening examination before the patient is released.

Will improving field care reduce costs and improve outcomes? Will it decrease less urgent uses of EMS and reduce transports of these lower-acuity patients? If that occurs, will reducing ambulance traffic be good for the emergency department? Might it reduce ED diversion and crowding?

Novel models in an evolving health care delivery platform that utilize mobile resources will be developed. There are already programs to provide follow-up care for patients released from inpatient status back to their home, patients with recurrent admissions for long-term health problems (eg, congestive heart failure), and patients with a variety of health problems who have demonstrated frequent use of EMS service in the past.5

In the current model, hospitals survive on revenue from inpatient service, and patients admitted through the emergency department after EMS transport are major contributors to that revenue stream. The cost of diversion, therefore, is significant. To calculate that cost, let’s count the average number of EMS patients arriving during the busy hours of the day (not including the middle of the night, when diversion is rarely utilized). Assume that arrival rate is a modest two EMS patients per hour. The average hospital revenue for ED services for those two patients is at least $1,000. If 40 percent of the EMS patients are admitted, and they generate $6,000 above the direct costs of service per patient, then ambulance diversion for five hours reduces hospital revenue by $6,000 in direct revenue for the 10 diverted patients plus $24,000 for the four diverted admissions. That $30,000 is a direct loss of $6,000 per hour, plus the loss of the patient for future visits and admissions as well as loss of relationship with EMS.

Today’s Positive EMS Relationship

As demonstrated above, positive cooperative relationships with EMS providers are critical. The ingredients for a positive EMS relationship include:

- Excellent clinical care for the patients brought by EMS

- Courtesy, respect, and professionalism shown to EMS providers

- Open beds for EMS patients to avoid off-loading delays

- Recognition for a job well done

- Respectful and professional communications about opportunities for improvement

- Cleaned and returned EMS supplies

- Replacement of disposable equipment and linens

- A reliable system for submitting EMS reports and including them in each patient’s medical record

- Offering EMS educational programs

- Cooperation with community programs (eg, disaster response)

Effective patient care should be provided at the right place and right time with the right equipment and personnel; it also should be provided at the right price and with the appropriate value. That requires cooperation between emergency physicians and EMS leaders. New systems of unscheduled care will require ED leaders to develop programs with EMS and those who pay for those services, including grant funders for these innovative programs.

References

- Minemyer P. CMS launches new model for paying ambulance crews—even if they don’t transport to the ER. Fierce Healthcare website. Feb. 14, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF, Valverde RH. Analysis of ambulance transports and diversions among US EDs. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(4):317-326.

- Diedrich J. Patients in ambulances still being turned away for hospitals even as some cities end the practice. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Mar. 11, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Diedrich J. Diverted into danger. USA Today. Jan. 30, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- McCluskey P. A new role for paramedics: treating patients at home. Boston Globe. Aug. 29, 2018. Accessed April 15, 2019.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “New Out-Of-Hospital Care Models Could Affect Your Emergency Dept”