An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) develops with age, occurring primarily in those older than 55 years. Risk factors include smoking, hypertension, male sex, atherosclerotic disease, and family history of AAA. Although AAA is less common in women, rupture is more common.1 Most aneurysms are less than 4 cm, with the normal diameter of the aorta less than 3 cm. When the aneurysm is greater than 5 cm, there is a risk of a rupture, which increases with increased aortic diameter.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 04 – April 2024The classic triad of abdominal pain, hypotension and pulsatile abdominal mass is present in less than 25 percent of patients.2 Patients can present with back pain, or with focal neurologic signs such as numbness of the lower extremity. A pulsatile abdominal mass may be difficult to assess in patients with a higher BMI. About 35 percent of individuals with rAAA will die at home.3 The majority of those who arrive to the emergency department (ED) live for 2 hours or more, leaving a small window for surgical intervention.4 Depending on the study, rAAA is missed in 16-62 percent of cases.5 Untreated, nearly all patients die. The diagnosis is confirmed with bedside ultrasound (US) or CT. Bedside US can confirm the presence of AAA, but visualization of the actual rupture may be more difficult because most AAAs rupture into the retroperitoneal space. CT is more definitive but can take more time.

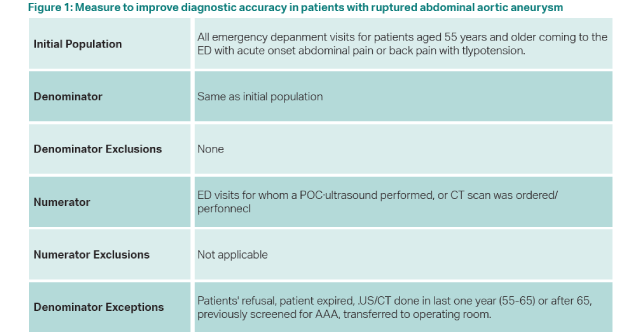

Recently, ACEP received a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to create a quality measure to improve the diagnostic accuracy of rAAA in patients. This measure has been approved by CMS and will be available for reporting soon. To meet the measure, and get credit for MIPS, all patients 55 years and older who present with new acute abdominal or back pain and hypotension (systolic BP less than 90mm Hg) must have an US or CT performed in the ED. Exceptions to this measure are patients who have been screened for an abdominal aortic aneurysm in the past, or have had a CT or US of the abdomen in the prior five years (for those 55-65 years old) or older than 65 years who demonstrate a normal size aorta. Other exceptions are patient refusal, patient death or immediate transfer to the operating room. It is hoped that more emergency physicians will use point of care bedside US, which can be performed more rapidly than a CT. Ultrasound of the aorta is a core competency of emergency physicians, but resources such as Sonoguide are available for a refresher at acep.org/sonoguide.

This measure has an additional advantage of increasing the number of patients screened for an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Screening (usually by US but can be by CT/MRI) is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) one time for men aged 65-75 who have ever smoked and should be considered in men aged 65-75 who never smoked, especially if there is a family history. The USPSTF is less clear on women, but screening can be considered in women aged 65-75 who have ever smoked.6 The Society for Vascular Surgery agrees with the one-time screening of men aged 65-75 who have ever smoked but also recommends screening men 55 and older (one time) who have a family history of AAA, and women 65 and older with a family history of AAA.7 They recommend consideration of screening women over 65 years with a significant smoking history.

rAAA is a rare entity, however screening identifies individuals at risk and allows for monitoring of smaller AAAs, and elective repair of larger AAAs to avoid rupture. Elective repair carries a much lower mortality/morbidity risk than emergency repair, even when the latter is performed using an endovascular technique. However, nationally just 40 percent of patients are screened. Patients in lower resourced and socioeconomic areas are less likely to be screened.8

Dr. Schneider currently is the Senior Vice President for Clinical Affairs at ACEP and adjunct professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Schneider currently is the Senior Vice President for Clinical Affairs at ACEP and adjunct professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Sweeting MJ, Thompson SG, Brown LC, et al. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to examine factors affecting growth and rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg 2012;99:655-665.

- Sayers R. Bailey & Love’s short practice of surgery, 26th ed. Boca Raton, FL:CRC Press; 2013.

- Gunnarsson K, Wanhainen A, Björck M, et al. Nationwide study of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms during twenty years (1994–2013). Ann Surg 2021; 274: e160-e166.

- Lloyd GM, Bown MJ, Norwood MG, et al. Feasibility of preoperative computer tomography in patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: a time-to-death study in patients without operation. J Vasc Surg. 2004 Apr;39:788-91.

- Metcalfe D, Sugand K, Thrumurthy SG, et al. Diagnosis of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: a multicentre cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2016; 23:386-90.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:2211-2218.

- Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. https://vascular.org/node/87. Accessed 2/3/24.

- Ho VT, Tran K, George EL, et al. Most privately insured patients do not receive Federally recommended abdominal aortic aneurysm screening. J Vasc Surg 2023;77:1669-`673.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “New Quality Measure Improves Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm”