The term “mass gathering” refers to a variety of different events including music festivals, concerts, state fairs, political rallies, sporting events like the Olympics and football games, public exhibitions, and the recent Pokémon GO game sensation. Mass gatherings are occurring more frequently globally.1 While the majority of attendees who seek medical attention have minor injuries or illnesses and commonly remain at the event, deaths are not infrequently reported in the academic and gray literature (ie, white papers and government documents).2,3 At music festivals between 1999 and 2014, 722 deaths were reported.3 Thus, onsite medical care has become an integral component of mass gatherings, and provisions for onsite resuscitation are critical to improve patient outcomes.4

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 04 – April 2017

James R. Kennedye MD, MPH, FACEP, of Tulsa, OK, helps Davi Millsaps up after a crash on the track during the Monster Energy Supercross races in Arlington, Texas.

Image Credit: Renée Fernandes/ReneeMedia

There is not a uniform consensus regarding the definition of a mass gathering. A mass gathering is commonly defined by a single characteristic of the event: the number of attendees. Some define a mass gathering as an event with more than 1,000 attendees, while others argue the minimum is 25,000 persons.5,6 Strictly defining a mass gathering by the number of attendees incorrectly suggests that attendance is the most important variable of an event. A broader definition of a mass gathering would be more useful. One authority defined a mass gathering as an event at which persons gather and the potential exists for delayed response to emergencies because of limited accessibility or the environment.7 The potential for delayed response requires advanced planning and preparation to allow timely access to appropriate medical care.

Mass-Gathering Medicine Literature

Reviews of mass-gathering medicine (MGM) literature repeatedly note that the existing literature is largely anecdotal or descriptive.2,7 MGM terminology and concepts are inconsistently defined and applied in the literature, leading to a relatively limited and non-standardized evidence base.8 For instance, event medicine and MGM are two synonymous terms referring to the same unique field of medicine. Pivotal details required to assess the impact of mass gatherings on local emergency medical services (EMS) and health care services are infrequently collected and analyzed.2 These deficiencies in data hinder the development of a core knowledge base. The unique challenges of providing adequate health care at mass gatherings are inadequately studied.

Mass gatherings have a higher incidence of injury and illness than is expected from the general population despite typically being gatherings of healthy persons.7,9 The reasons for this are incompletely understood. Variables affecting patient presentation rates (PPRs) at mass gatherings include type of event, ambient temperature, drug use and resultant toxicity, and availability of free water. Events with increased PPRs require greater resources, medical staffing, preparation, and disaster planning. As the field of event medicine develops, goals include standardized data collection, collaboration among researchers, and the development of a minimum core competency of knowledge for clinical providers and the attendant medical directors who work at these events. An international multidisciplinary group has begun to develop agreement on key concepts, data definitions, and a minimum data set.8 The overarching goal of MGM is to offer a multidisciplinary health care team capable of decreasing PPRs, optimizing onsite care by providing care similar to that available in emergency departments, and minimizing the effect of the event on local health care resources.

Demographics of Attendees

In one recent large Australian study of nearly 5,000 patients at mass gatherings, females were shown to be more frequent utilizers of onsite medical care (62.4 percent), contradicting other studies finding equal gender distribution or slightly higher male medical usage rates (MURs).9,10 The majority of patients were younger than 25 years of age (78.3 percent). The most common complaints in descending order were headache, lacerations, sprains, pain, asthma, and nausea/vomiting. Females sustained injuries at half the rate as males (odds ratio, 0.54; 95 percent CI, 0.47–0.62; P <.001). The majority of the critical non-traumatic illness that occurs at music festivals arises from 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and associated adulterant toxicity.11 MDMA, known as “ecstasy” in pill form and “molly” in powder form, has been popularized as an illicit recreational drug commonly used at electronic dance music events. Fatalities in the United States attributed to MDMA use were first reported in 1987.12

Predictive Variables

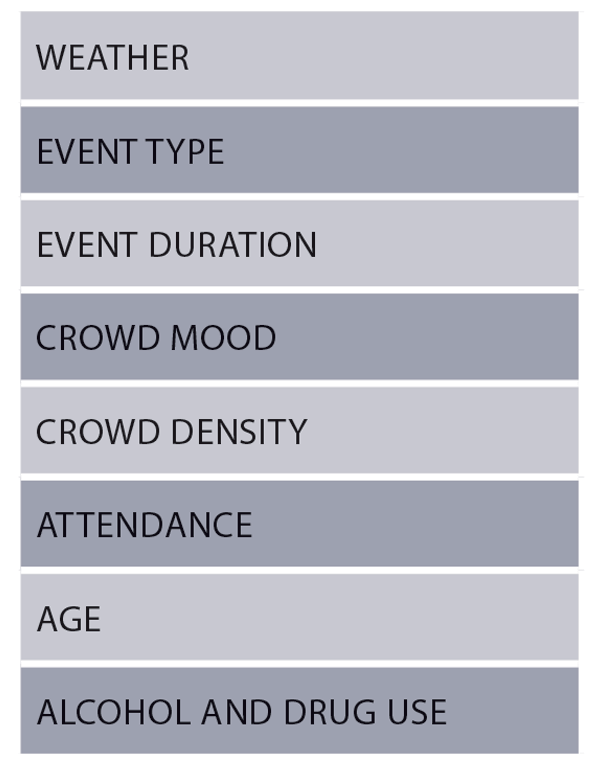

Table 1: Key Variables Affecting Patient Presentation Rate

A literature review identified multiple interacting variables that affect the MUR.9 The following variables (see Table 1) contribute significantly to the PPRs: ambient temperature, event type, event duration, crowd mood, crowd density, attendance, average age, and the prevalence of alcohol and drug use. Cold and rainy days generally lead to lower PPRs but with a higher incidence of hypothermia, frostbite, and falls, while hot weather leads to higher PPRs for dehydration, insect bites, and sunburns.9 Rock concerts have a positive correlation with trauma (often secondary to moshing and crowd surfing).9 At music concerts, attendees often have limited mobility and consume drugs and excessive amounts of alcohol, leading to higher PPRs. Event duration extends exposure and increases exhaustion.9 Crowd density may affect crowd mood, limit access of patrons to water and facilities, and limit EMS access to potential patients.9 Interestingly, PPRs tend to decrease with higher attendance (ie, as the number of spectators increases, the number of patients evaluated per 10,000 in attendance decreases).9 The reasons for this are not understood.

Younger adult spectators use more alcohol and drugs than older spectators and have increased trauma, often secondary to physical altercations.9 Age distribution of a particular event is also a key variable as medical and social issues for older patrons differ widely from those of younger crowds due to their behavior, judgment, frailty, and vulnerability.9

Heat index is associated directly with PPRs.13 The heat index at the kickoff times of football games in the southeastern United States was compared to the PPRs for the games over the course of four years. For every 10-degree increase in the heat index, three more patients per 10,000 patrons required medical care.

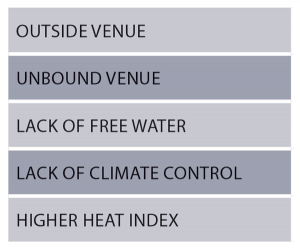

Table 2: Variables That Predict Increased Patient Presentation Rate

Five variables (see Table 2) are known to increase PPR: unbounded venues, outdoor venues, events lacking free water, lack of climate control, and a higher heat index. 5 Thus, medical staffing should be especially prepared if these risk factors exist. After accounting for these other variables, the presence of alcohol does not increase the PPR.

Conclusion

The following actions can improve patient safety at mass gatherings as described in a recent prospective analysis of patients at a large outdoor summertime mass gathering: develop and drill incident action plans in preparation for disaster scenarios and mass casualty incidents; use roaming, clearly identified medical staff; provide free water for attendees; designate multiple access points for EMS in the event of transport or a mass casualty incident; and use trained medical staff capable of administering rapid cooling, benzodiazepines, and advanced airway management, including rapid sequence intubation.14

Dr. Chan is a PGY-2 emergency medicine resident at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York.

Dr. Chan is a PGY-2 emergency medicine resident at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York.

Dr. Friedman is associate medical director of prehospital care and director of the EMS clerkship in the department of emergency medicine at Maimonides Medical Center.

Dr. Friedman is associate medical director of prehospital care and director of the EMS clerkship in the department of emergency medicine at Maimonides Medical Center.

References

- Hutton A, Ranse J, Verdonk N, et al. Understanding the characteristics of patient presentations of young people at outdoor music festivals. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2014;29(2):160-166.

- Ranse J, Hutton A, Keene T, et al. Health service impact from mass gatherings: a systematic literature review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(1):71-77.

- Turris SA, Lund A. Mortality at music festivals: academic and grey literature for case finding. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(1):58-63.

- Wassertheil J, Keane G, Fisher N, et al. Cardiac arrest outcomes at the Melbourne Cricket Ground and shrine of remembrance using a tiered response strategy–a forerunner to public access defibrillation. Resuscitation. 2000;44(2):97-104.

- Locoh-Donou S, Yan G, Berry T, et al. Mass gathering medicine: event factors predicting patient presentation rates. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11(5):745-752.

- Ranse J, Hutton A. Minimum data set for mass-gathering health research and evaluation: a discussion paper. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012;27(6):543-550.

- Arbon P. Mass gathering medicine: a review of the evidence and future directions for research. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2007;22(2):131-135.

- Turris SA, Steenkamp M, Lund A, et al. International consensus on key concepts and data definitions for mass-gathering health: process and progress. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(2):220-223.

- Milsten AM, Maguire BJ, Bissell RA, et al. Mass-gathering medical care: a review of the literature. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2002;17(3):151-162.

- Krul J, Girbes AB. Experience of health-related problems during house parties in the Netherlands: nine years of experience in three million visitors. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(2):133-139.

- Ganguly S, Friedman M, Bazos AN. Raves and saves: massive music festivals call for advanced emergency care. Emerg Physicians Monthly. 2014;21(9).

- Dowling GP, McDonough ET 3rd, Bost RO. ‘Eve’ and ‘ecstasy’. A report of five deaths associated with the use of MDEA and MDMA. JAMA. 1987;257(12):1615-1617.

- Perron AD, Brady WJ, Custalow CB, et al. Association of heat index and patient volume at mass gathering event. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9(1):49-52.

- Friedman MS, Plocki A, Likourezos A, et al. A prospective analysis of patients presenting for medical attention at a large electronic dance music festival. Prehosp Disast Med. 2017;32(1):78-82.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Onsite Medical Care, Resuscitation Increasingly Important at Mass Gathering Events”