Until now, the window to treat acute stroke with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or endovascular thrombectomy was six hours, maximum. Many centers wouldn’t administer tPA after four hours.

Until now, the window to treat acute stroke with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or endovascular thrombectomy was six hours, maximum. Many centers wouldn’t administer tPA after four hours.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 04 – April 2018Although many emergency physicians can attest to the professional satisfaction of successfully administering treatment to a patient who otherwise would have had a lifelong, debilitating neurologic deficit, most can also point to the intense frustration felt when a patient presented with a stroke that fell outside the treatment window. The treatment time limit cruelly limited the number of patients who could regain the ability to move or speak.

Progress has been made in the implementation of operational efficiencies to facilitate the early, prehospital identification of stroke symptoms; rapid EMS stroke diagnosis; rapid CT imaging; and, if appropriate, the timely administration of tPA and thrombectomy. However, the six hour problem remained—endovascular thrombectomy was previously recommended only if performed within six hours of symptom onset.

But we have good news: With the recent publications of the DAWN and DEFUSE3 trials, there’s new hope.

The DAWN trial demonstrated that select patients with acute ischemic stroke presenting from 6–24 hours of symptom onset have improved 90-day outcomes after mechanical thrombectomy compared to medical therapy alone.1

The DEFUSE3 trial showed similar results of improved outcomes with endovascular thrombectomy for ischemic stroke patients 6–16 hours after they were last known to be well.2 The patients best served featured proximal middle-cerebral-artery or internal-carotid-artery occlusion, and a region of tissue that was ischemic but not yet infarcted.

This evolving treatment paradigm, while groundbreaking, requires new emergency department and collaborative workflows to identify appropriate stroke patients and activate the correct treatment pathway.

A New Stroke Protocol

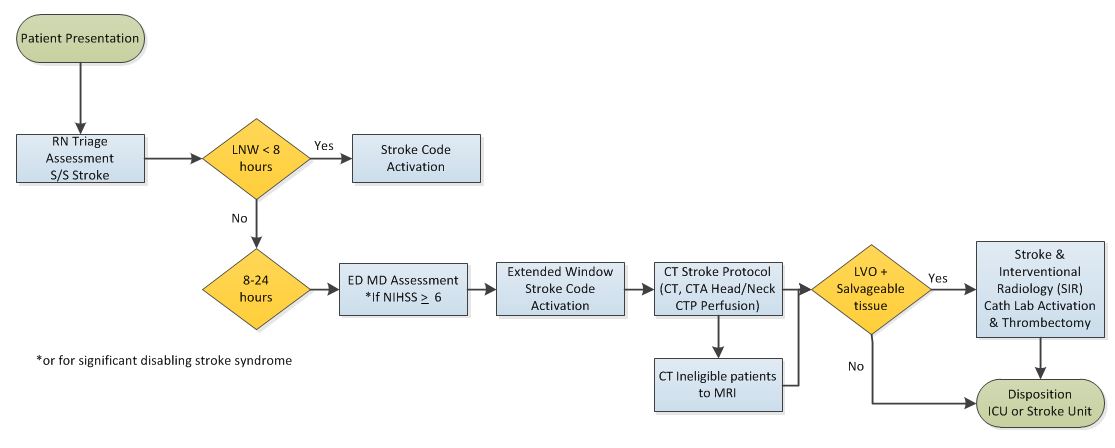

Stanford University’s department of emergency medicine collaborated closely with other departments to develop a novel Stroke Code Extended protocol that expedites evaluation and treatment of patients with large-vessel

debilitating strokes that, prior to the protocol, would have limited treatment options. The protocol was crafted by a multidisciplinary team of stakeholders from the departments of neurology, emergency medicine, nursing, radiology, and hospital staff. We designed and implemented the new stroke code process using quality improvement principles, such as adherence to standard work, pre-existing protocol preservation, planned outcome measures, and widespread education. Mock code simulations provided iterative feedback before we launched the process.

The team created the protocol for patients presenting with stroke symptoms at 8–24 hours without changing the pre-existing code process for patients presenting before 8 hours (see Figure 1). Emergency physicians rapidly triage and activate all stroke codes if the patient presents as greater than or equal to 6 on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). However, the new protocol excludes a bedside pharmacy evaluation and moves directly to alerting the stroke team to come to the patient’s bedside in the emergency department.

Other unique protocol elements include expedited CT angiogram and perfusion imaging, and mobilization of the interventional neuroradiology team for thrombectomy. The CT angiogram and perfusion imaging is critical in determining the amount of brain tissue at risk of infarct, and therefore whether thrombectomy would be indicated. To determine patients appropriate for thrombectomy with adequate salvageable tissue, the team looks at the ratio of ischemic tissue to the initial infarct volume (ischemic core), and an absolute volume of potentially reversible ischemia (penumbra).

The Stroke Code Extended also requires the emergency department attending to perform and document a NIHSS score on all suspected stroke patients. Although this is a core emergency medicine skill, Stanford instituted an educational initiative to certify our entire faculty and residency in performing the assessment. This was accomplished through online training modules and traditional lecture-style didactics.

In addition, immediately upon arrival at the bedside, the neurology resident now performs an NIHSS stroke scale assessment. Our goal is to study the inter-rater reliability between neurology- and emergency medicine-completed NIHSS stroke scales.

Beyond the New Protocol

Parallel to our initiative to identify and treat extended strokes, Stanford’s neurology department has performed significant educational outreach to referral hospitals to facilitate the rapid transport of stroke patients to Stanford Hospital even if they’re outside the tPA window but still likely to benefit from thrombectomy. In addition, the Stanford School of Medicine has found that collaboration between the emergency medicine and neurology departments is instrumental in improving the treatment of acute stroke.

Looking ahead, we will evaluate the implementation of this protocol by collecting stroke quality metrics, measuring NIHSS inter-rater reliability, and monitoring the stroke mimic rate. We look forward to sharing further insights about our protocol and results.

Dr. Wagner is assistant director of Adult Emergency Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

Dr. Wagner is assistant director of Adult Emergency Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

Dr. Shen is the interim chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

Dr. Shen is the interim chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

References

- Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):11-21.

- Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):708-718.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Opinion: Stanford’s New Stroke Protocol Expands the Treatment Window”