Emergency physicians have been tasked not only with providing safe and accurate care but also with stewardship of society’s scarce resources. Among other things, this means outpatient management of some disease entities traditionally managed in an inpatient setting.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 08 – August 2016Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a relatively common condition, having lifetime prevalence of up to 5 percent, and is commonly first diagnosed in the emergency department.1,2 Massive proximal DVT can lead to phlegmasia alba, which is itself limb-threatening. Pulmonary embolism is a frequent complication, and in patients with patent foramen ovale, paradoxic/systemic thromboembolic complications such as stroke can develop. Late morbidity of venous thromboembolism (VTE) such as postphlebitic syndrome characterized by extremity edema and pain, stasis dermatitis, and, in severe cases, ulcer formation, as well as pulmonary hypertension, is well-described. Timely therapy reduces the rate of these complications.

Systemic anticoagulation for DVT may include therapeutic dosages of unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), rivaroxaban, or fondaparinux. Alternatives such as vena cava filters and mechanical clot removal in patients with contraindications to anticoagulation exist, but they are outside the practice of emergency medicine. Since development of LMWH in the late-20th century, the option for discharge of select patients with DVT from the emergency department became viable. This has the potential to improve quality of life, increase patient convenience, and reduce health care expenditures.1,3–5 Outpatient management of DVT was slow to catch on. One report of patients diagnosed with DVT treated from 2003 to 2007 noted that only 28 percent of patients were treated as outpatients.6

After the diagnosis is established, it should be decided if the patient is appropriate for outpatient management. Those with iliofemoral clot, unstable clot visualized on ultrasound, severe comorbid conditions, or unstable social situations make poor candidates for discharge from the emergency department. There is a paucity of data on outpatient management of upper-extremity DVT. Special attention should be paid to the patient’s risk of bleeding once anticoagulated. In addition to the physician’s judgment, there are tools such as the Registry of Patients with Venous Thromboembolism (RIETE) score (available at www.mdcalc.com/riete-score-risk-hemorrhage-pulmonary-embolism-treatment) for assistance in determining suitability for outpatient management. Patients judged to be a higher risk should be given an easily reversible agent and monitored in the hospital initially.

Since development of LMWH in the late-20th century, the option for discharge of select patients with DVT from the emergency department became viable. This has the potential to improve quality of life, increase patient convenience, and reduce health care expenditures.

As there are currently multiple pharmacologic options for anticoagulation (see Table 1), it is important for emergency physicians to be well-informed to choose the best option for their patients. Current options include the following agents: LMWH, enoxaparin, dalteparin, tinzaparin, nadroparin, fondaparinux, warfarin, and the novel anticoagulants (NOACs) dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. If the patient is prescribed warfarin, then therapeutic dosages of an unfractionated heparin should be given for five days until the international normalized ratio (INR) is therapeutic. Starting warfarin at 10 mg per day on days one and two has been recommended as safe and able to achieve a therapeutic INR more rapidly than 5 mg daily.1,2 Regular monitoring of the INR for patients taking warfarin is necessary due to wide individual genetic differences to warfarin response as well as to the wide number of medication interactions with warfarin. NOACs are attractive alternatives due to their oral route of administration, quick and predictable onset of action, and avoidance of repeat blood draws to monitor coagulation parameters. Studies suggest that NOACs are non-inferior to warfarin with regard to DVT complications and risk of bleeding.7 NOACs are renally excreted but have not been well-studied in patients with creatinine clearance levels less than 30 µmol/L.

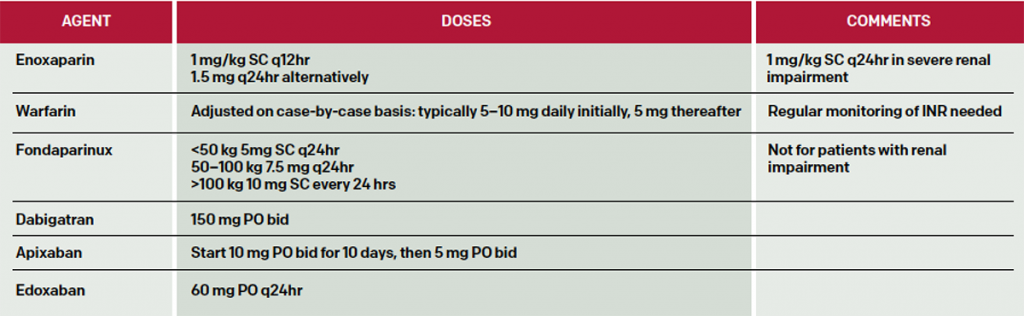

Suggested doses of anticoagulants are listed in Table 2. Here are short summaries of selected agents.

LMWHs are preferred agents for treatment of DVT in pregnancy, DVT in cancer patients, and patients with procoagulant disorders.2 Enoxaparin (Lovenox) is administered at 1 mg subcutaneously (SC) every 12 hours or 1.5 mg/kg daily. Dalteparin (Fragmin) is typically dosed at 200 units/kg SC daily for one month, then 150 units/kg Sc thereafter. LMWHs are renally excreted, and dosing must be modified for renal insufficiency.

(click for larger image)

Table 2: Selected Dosing of Anticoagulants in Patients with DVT. Note that limited data are available for morbidly obese patients, while patients with mass less than 57 kg for men and less than 45 kg for women are at increased risk of bleeding with heparins.1,2

While generally safe, a subset of patients will develop life-threatening bleeding complications while anticoagulated. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), with its risk of extensive thrombotic complications, is less likely to occur with LMWHs than with unfractionated heparin but still mandates discontinuation of these agents, including unfractionated heparin, for the rest of the patient’s life.

The limitations of warfarin prompted the development of NOACs, which produce a predictable anticoagulant response without requiring routine monitoring.

Fondaparinux (Arixtra) is an indirect factor Xa inhibitor. It lacks cross-reactivity with heparin-induced antibodies and can be administered to patients diagnosed with HIT. Since it is 100 percent renally cleared, the patient must have a creatinine clearance of at least 30 mL/minute and preferably more than 50 mL/minute. It is typically weight-dosed, with 5 mg/day SC prescribed daily for patients less than 50 kg, 7.5 mg daily if the patient weighs 50–100 kg, and 10 mg/day SC for patients weighing more than 100 kg.

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) is an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor. It may be used for acute and long-term treatment of DVT. As with LMWHs, it may not be appropriate for use in patients with renal insufficiency. It is typically started at 15 mg orally twice daily for three weeks, then 20 mg orally each day. It has been shown to be non-inferior to LMWHs, with similar or fewer major hemorrhages.

Apixaban (Eliquis), another factor Xa inhibitor, is administered at 10 mg orally twice daily for 10 days, then at 5 mg daily thereafter. Edoxaban (Savaysa), the third approved factor Xa inhibitor, is typically dosed at 60 mg orally per day, although it has been dosed at 15–30 mg daily for patients weighing less than 60 kg or with a creatinine clearance of 15–50 mL/minute. All of the factor Xa inhibitors are relatively expensive compared to warfarin, with 30-day cost to pharmacy cited in the $277–$315 range.8

There are no approved reversal agents for the factor Xa inhibitors. It should be noted that several molecules are being studied as potential reversal agents for NOACs.9 When there is an effective reversal agent available, NOAC indications may broaden.2 It is unclear how effective prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) are in reversing anticoagulation effects of the factor Xa inhibitors, but they may be a treatment option for now until specific antidotes are approved.

Dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) is a direct thrombin inhibitor dosed typically at 150 mg twice daily orally for patients with creatinine clearance of more than 30 mL/minute after seven to 10 days of parenteral anticoagulation. It is approved for treatment of VTE in the United States. For emergency bleeding or for preparation for emergency surgery, a monoclonal antibody idarucizumab (Praxbind) is available to reverse its effects, given in 2.5 gm IV for two doses, no more than 15 minutes apart.9 Supratherapeutic levels of dabigatran may occur in patients with decreased renal function.

Conclusions

The emergency physician has a variety of options for managing patients with DVT as outpatients. Clearly, patients’ renal function, reliability, and support system will dictate the optimal treatment course.

Dr. Garber is an attending physician at MetroHealth Medical Center and assistant professor at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, both in Cleveland. Dr. Glauser is on the faculty of the Emergency Medicine Residency Program at MetroHealth Medical Center and professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University.

References

- Wells PS, Forgie MA, Rodger MA. Treatment of venous thromboembolism. JAMA. 2014;311(7):717-728.

- Yeh CH, Gross PL, Weitz JI. Evolving use of new oral anticoagulants for treatment of venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2014; 124(7):1020-1028.

- Zakai NA, McClure LA, Lutsey P, et al. Adoption of outpatient treatment of deep vein thrombosis in the U.S.: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study (REGARDS) [abstract]. Blood. 2014;686.

- Lozano F, Trujillo-Santos J, Barron M, et al. Home versus in-hospital treatment of patients with acute deep venous thrombosis of the lower limbs. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:1362-1327.

- Fahad M, Al-Hameed MD, Hasan M, et al. The Saudi clinical practice guideline for the treatment of venous thromboembolism: outpatient versus inpatient management. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(8):1004-1010.

- Zakai NA, McClure LA, Lutsey PL, et al. Adoption of outpatient treatment of deep vein thrombosis in the US: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study (REGARDS). 56th American Society of hematology (ASH) Meeting and Exposition, Dec 2014. Abstr

- Kakkos SK, Kirkilesis GI, Tsolakis IA. Efficacy and safety of the new oral anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban in the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of phase III trials. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48(5):565-575.

- Edoxaban (savaysa) – the fourth new oral anticoagulant. The Medical Letter. 2015;57(1465):43-44.

- Hu TY, Vaidya VR, Asirvatham SJ. Reversing anticoagulant effects of novel oral anticoagulants: role of ciraparantag, andexanet alfa, and idarucizumab. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:35-44.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

4 Responses to “Options, Approaches to Outpatient Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis for Emergency Physicians”

August 24, 2016

Sunjeev Konduru, MS, PharmD, BCPSThe dosing of apixaban in this article does not match the FDA prescribing information, which states give 10mg twice a day for 7 days, followed by 5mg twice a day. This dose of Eliquis was studied in the AMPLIFY trial for 6 months versus lovenox and warfarin in patients with symptomatic PE or proximal DVT.

Edoxaban also required initial parenteral anticoagulation for 5 to 10 days, similar to dabigatran.

Thank you.

August 28, 2016

jakeYou correctly point out dabigatran as a direct thrombin inhibitor in the text of the article, however, in the table it is incorrectly listed as a Xa inhibitor.

August 30, 2016

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you, the table has been updated to reflect this correction.

August 29, 2016

Soumya Ganapathy MDGreat article. When treating DVTs and PEs as an outpatient, patient education is paramount. Patient and their families can often feel overwhelmed. ACEP has a program called knowbloodclots.com, it is a great resource for patient education on DVTs and PEs. They have nice videos like what to expect with DVT and PE treatment as well as warning videos on the risk of bleeding. They also have a free texting program that sends reminders and educational links to patients.