The emergency department at Houlton Regional Hospital (HRH) in Houlton, Maine, wanted to take its operational performance to the next level. This Critical Access Hospital (CAH) seeing 11,000 visits a year struggled with patient surges. As is the case in many CAHs, HRH was challenged with recruiting new physicians, especially hospitalists, who are so critical to ED flow. (Approximately 25 percent of Americans choose to live in rural areas, while only 10 percent of physicians choose to practice there.) Further, the emergency department has only single coverage, and was easily overwhelmed by one critically ill patient. Finally, HRH struggled to manage the behavioral health burden in its nine-bed emergency department.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 06 – June 2017CEO Tom Moakler, ED Medical Director Brian Griffin, and Nursing Director Tricia Murray wanted to re-engineer patient flow in their department during peak flow times to improve efficiency. They began with an ambitious change package:

- Redesign intake

- Repurpose triage as a rapid treatment unit (RTU) (low-acuity service line)

- Re-engineer patient flow for high-flow/low-flow times of the day

- Develop a night plan with the hospitalists

Redesign Intake

The emergency department had continued to use traditional nurse triage and booth registration, followed by traditional ED patient flow. This did not serve it well during peak arrival times. The leadership did a number of things that help expedite intake and patient care in the single-covered emergency department.1 Traditional triage was replaced with an abbreviated triage and a “pull-to-full” model to bring the patients, provider, nurses, and registration to the bedside.2 This takes all of the steps of intake and conducts them in parallel instead of in series, which is inarguably more efficient.

CEO Tom Moakler, ED Medical Director Brian Griffin, and Nursing Director Tricia Murray (left to right).

Houlton Regional Hospital’s rapid treatment unit area serves as a place to care for low-acuity patients.

Repurpose Triage as an RTU

The former triage area is now the RTU area, which serves as a place to care for low-acuity patients rather than placing them in a traditional bed. In the old flow model, low-acuity patients often suffered long waits and delays because no resources were dedicated to them. This new low-acuity zone cannot support its own provider, but it can have nurses and staff dedicated to the rapid processing of patients. In addition, nurses are empowered to begin standardized, chief complaint–driven order sets. This has long been recognized as a best practice, particularly in single-coverage departments, so that patients are always moving along their patient flow journey.

(click for larger image)

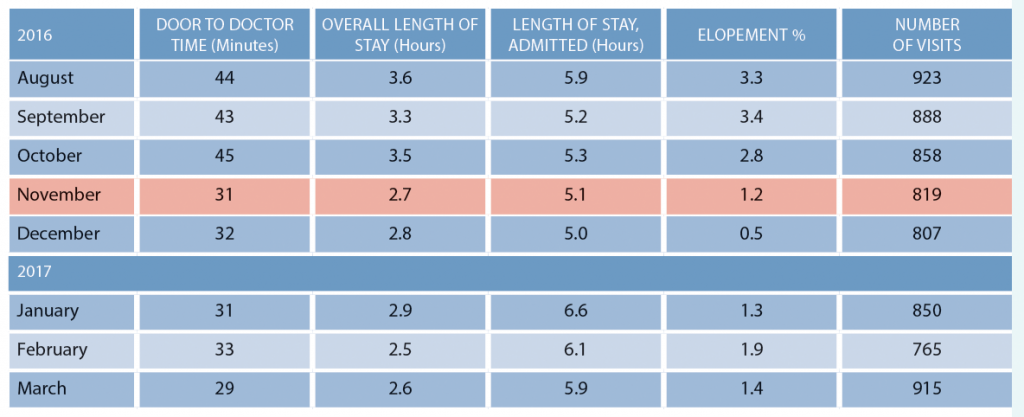

Table 1: Houlton Regional Hospital Metrics Before and After Implementing Patient Flow Changes in November 2016

Re-Engineer Flow for High Flow and Low Flow

The leadership also articulated a process for times of the day when all nine beds are full (high flow).3 During these times, the provider sees new patients in the RTU (one specified chair) until beds are available. Diagnostic testing is started, and patients are managed in the waiting room until treatment spaces open up. Emergency Severity Index 1 and 2 patients are accommodated in the main emergency department by moving less-acute patients out.

Develop a Night Plan with the Hospitalists

Finally, like many rural hospitals, the department struggled with on-call coverage at night. The heavy lifting was being done by the hospitalists, who admitted the majority of patients. However, the hospitalists were working seven days straight and were wearing out quickly. The hospitalists needed to have a few hours on the night shift to get sleep, but the emergency department wanted to get its patients bedded down on the inpatient units. The solution was the implementation of “holding orders,” also known as “bridge orders” or “timed-out orders.”4

The before and after data in Table 1 are very impressive.

Hats off to the Houlton Regional leaders. When you think you can’t take your emergency department to the next level of operational performance, just remember “The Maine Thing.”

References

- Welch S, Davidson S. Exploring new intake models for the emergency department. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(3):172-180.

- Augustine J. ‘Pull to full’ speeds up flow. ED Manag. 2011;23(3):30-31.

- Welch S, Savitz L. Exploring strategies to improve emergency department intake. J Emerg Med, 2012;43(1):149-158.

- Traub SJ, Temkit M, Saghafian S. Emergency department holding orders. J Emerg Med. 2017; pii: S0736-4679(17)30110-5.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Patient Flow Improvements to Boost Efficiency in Small Emergency Departments”

July 5, 2017

ToddI am surprised how casually bridge orders are mentioned as a component to improving ED throughput.

ACEP explicitly has a written policy discouraging this practice, and rightfully so:

https://www.acep.org/Clinical—Practice-Management/Writing-Admission-and-Transition-Orders/