Differences, advantages, and pitfalls of working as an IC versus a hospital employee in the ED

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 01 – January 2014The transition from resident to attending—and through other career transitions—is often filled with mystery and angst about the unknown. Many physicians live by the motto, “Frequently wrong, but never in doubt!” This recurring column will present questions asked by those seeking info, answered by those in the know.

In the bad old days, when emergency medicine was in its infancy and struggling to carve out its niche, practicing as an independent contractor (IC) was nearly universal. The structure was relatively simple to set up and relatively cheap to administer, and most of the physicians worked in more than one emergency department. Then, in the early 1990s, the IRS began auditing EM IC agreements and, in many cases, ruled that the emergency physicians did not meet the IRS IC “20-point test.” A few of these points are that ICs must set their own schedule, supply their own tools, and perform their role however they see fit. The full list is at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/x-26-07.pdf. The IRS has a vested interest in monitoring ICs because ICs don’t pay employment taxes until they distribute compensation and they pay quarterly estimated income tax withholding rather than monthly. This deprives the IRS of a steady flow of employment tax and withholding revenue. Of course, there is also the potential issue of abuse, such as writing off things not truly related to business expenses.

The employer-employee structure didn’t come to predominate until the mid-1990s with the government’s decision to prohibit provider reassignment of their patient fees to the group for IC relationships. This bit of “help” from the government made emergency medicine group-practice management and administration for groups treating their provider members as ICs infinitely more complex and expensive. Physicians in the group now had to have their own bank accounts with full access, and all payments from the government payers generated by each physician could only be deposited in that account. All things considered, the easiest path to compliance was simply to convert the group to employer-employee, and that’s what happened. Just about the time everyone made the transition, ACEP’s lobbying efforts paid off, and in 2003, President George W. Bush signed legislation rescinding the change in reassignment rules, making the IC structure a viable option once again.

Employers can dictate your schedule and how you do your job; in an IC structure they aren’t permitted to do either of these things, which can be a real problem for the group practice of emergency medicine.

Fast-forward to the threshold of 2014 and the full implementation of the Affordable Care Act: we find significant renewed interest in the IC structure. Part-time employees working fewer than 28 hours per week and ICs are exempt from the Act’s employer mandate (but not the individual mandate). Therefore, many people are being forced to consider the IC model by their employers. So let’s look at some of the distinctions between the two models.

Employers typically pay 50 percent of employees’ Social Security and Medicare taxes (generally about 7.65 percent of gross compensation), whereas ICs must pay both halves, or 15.3 percent. Employers typically provide benefits like personal time off, paid vacations, health insurance, and retirement plans. ICs receive none of these benefits. Primarily because of these two facts, ICs are generally paid a higher hourly wage than employees to make up at least some of the difference.

Employers withhold employees’ estimated federal and state income taxes with each paycheck. ICs must estimate their own withholding obligation and pay it to the government on a quarterly basis. Employees get a W-2 at the end of the year, whereas ICs get a Form 1099.

Employers can dictate employees’ schedules and how they do their jobs. In an IC structure, they aren’t permitted to do either of these things, which can be a real problem for the group practice of emergency medicine.

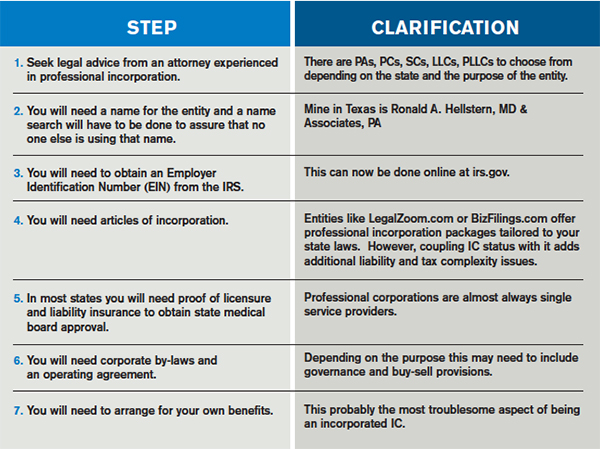

ICs are their own small businesses contracting with other small businesses to provide their services. They receive a gross sum for their services, out of which they must pay their employment taxes and a quarterly estimated income tax amount, fund whatever benefits they choose for themselves, and, in most cases, buy their own malpractice liability insurance. Depending on the state they are in, they may be able to write off certain business-related expenses—whether they are individually incorporated or not. In others, it’s best to form a professional association (PA) or professional corporation (PC). A corporate structure is generally essential to maximizing retirement-plan contributions.

But being an IC is not all positive. In an employer-employee structure, the practice only has to have one set of books, one malpractice policy, and one benefits plan, plus file just one tax return. Each IC working for the group, on the other hand, has all of these same expenses individually, making the annual PA/PC carrying cost $3,000–$5,000. Also, ICs don’t have the statutory protections afforded most employees, such as due process and overtime pay. In most states, a PA or PC cannot own stock in a non-PA/PC company, making for some difficult ownership issues. Neither can a non-physician spouse own PA or PC stock.

To sum up, being an IC is a viable emergency medicine practice option with its own set of pros and cons. Because it is extremely important to meet the IRS’ IC test criteria, some legal guidance in setting up the structure is essential. The structure also has to work for an IC’s employer(s) because, in general, having both employees and ICs doing the same full-time job is a red flag for an IRS audit.

Ronald A. Hellstern, MD, FACEP, is principal and president of Medical Practice Productivity Consultants, PA and a partner in Hospital Practice Consultants, LLC in Dallas.

Ronald A. Hellstern, MD, FACEP, is principal and president of Medical Practice Productivity Consultants, PA and a partner in Hospital Practice Consultants, LLC in Dallas.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Pros and Cons of Independent Contractor Status for ED Physicians”