Can you remember the last time you worked a shift in the emergency department and ordered zero computed tomography (CT) scans? Can you even imagine a time in history when the number of CT scans to rule out pulmonary embolism ordered was compiled in a monthly total rather than a daily report? There was, indeed, a time when it was not so common to parade a CT about town in such innovations as mobile stroke units.

Explore This Issue

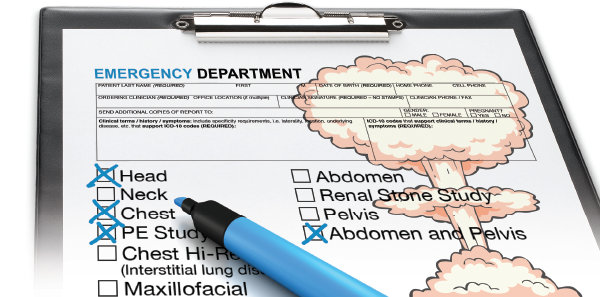

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 06 – June 2016With minimal barriers to use and the appeal of diagnostic certainty, CT use has spiraled out of control. Choosing Wisely implicates excessive use of advanced imaging as low-value care consumers should question. Despite ACEP publishing its own recommendations for avoiding low-value imaging and the known financial and physiologic harms of CT overuse, the literature remains replete with examples of inappropriate use. In even just the past few months, multiple publications have indicted a wide variety of imaging modalities:

Cervical Spine Imaging in Trauma

The ground-level fall is an extraordinarily common presenting mechanism of injury. Some days it seems nearly every single nursing home resident spends their day innovating new ways to evade their caregivers and find their way down to the floor.

These patients frequently arrive fully immobilized in full trauma regalia and undergo CT of the cervical spine for clearance. This single-center review of 760 ground-level fall presentations identified seven fractures—six stable and one unstable.1 The authors further reviewed each chart individually and suggested only 50 percent of charts supplied sufficient documentation to support appropriateness of imaging according to National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) Low-Risk Criteria or Canadian Cervical-Spine Rule. Conversely, at least 20 percent of charts supplied enough information to judge imaging as definitely inappropriate.

The authors estimate consistent use of validated decision instruments just for ground-level falls could reduce imaging-related costs $12–$31 million annually in the United States.

Pulmonary Embolism

The ACEP Clinical Policy Statement for the evaluation of pulmonary embolism (PE) is clear: In patients with a low pretest probability for suspected PE, the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) can be used to exclude the diagnosis based on history and physical alone.2 This statement is not an endorsement of PERC as a “zero miss” decision instrument but, rather, recognition of the harms relating to long-term anticoagulation and the generally low morbidity and mortality of PE in the setting of preserved normal physiology. The harms are likely understated as the acceptable miss rate used in PERC does not account for the high rates of false positives recognized in patients with low pretest probability for PE. In the interests of protecting patients and decreasing unnecessary CT use, the rate of CT for PE in PERC-negative patients should be nearly zero.

Stojanovska and colleagues present a review of cases from an academic medical center in the Midwest, retrospectively reviewing 602 CT for PE.3 The overall yield was reported as almost 10 percent, which is sadly unexceptional in the United States. More concerning, almost 20 percent of patients scanned were PERC negative. If a major teaching institution is misusing CT for PE in low-yield and low-value presentations, how will our trainees perform in the future?

Appendicitis in Children

Children, as they say, are our future. If this truism holds, our future is full of solid tumor diagnoses.

The evaluation and treatment of children in the emergency department exhibits some of the widest possible variation. This is to be expected given the gulfs of experience and comfort with pediatric patients. Harms should be avoided when they can be. For example, ultrasound-first strategies for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis are reasonable and widespread. Not every presentation is appropriate to forgo CT, but many uncomplicated presentations can feasibly be addressed first by ultrasound.

This article demonstrates the use of ultrasound deteriorates rapidly with distance from pediatric specialty centers.4 Comparing a pediatric emergency service at an academic center to a community-based practice still with pediatric emergency coverage, the rate of CT imaging was roughly triple in the community. At the academic center, fewer children with abdominal pain received lab work, and of those receiving lab work, only 10 percent underwent CT. Comparatively, at the community facility, a greater percentage of abdominal pain presentations received blood work, and 28 percent of those underwent CT. The difference boiled down to avoidance of CT by use of ultrasound and by admissions for clinical observation.

Ultrasound or observation-first protocols are widespread and certainly defensible foundations for shared decision making.

Harms should be avoided when they can be. For example, ultrasound-first strategies for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis are reasonable and widespread. Not every presentation is appropriate to forgo CT, but many uncomplicated presentations can feasibly be addressed first by ultrasound

Upper Respiratory Infections

Finally, just to complete our comedy of errors, we’re also now seeing extensive use of CT for even benign upper respiratory infections (URI). It is reasonable to have a serious debate over the risks, benefits, and diagnostic certainty for illnesses of significant morbidity and mortality, but the common cold?

These authors reviewed the use of CT for emergency department visits coded as URI or lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI).5 In 2001, only 0.5 percent of patients visiting the emergency department for URI symptoms received a CT, and by 2010, that rate had climbed to 3.6 percent. In 2001, 3.1 percent of LRTI symptom presentations received a CT, and in 2010, this rate had climbed to 12.1 percent. In keeping with classic features of overuse, there was no change in rate of antibiotic prescribing or the rate of hospital admission. Four times as many CT scans with zero benefit.

Undifferentiated Chest Pain

Flipping the channel a bit, this last article concerns not just CT overuse but suggests irresponsible overuse.

Institutions are increasingly adopting HEART score-based algorithms for early discharge. Recent publications call widespread provocative testing into question.6

However, the proponents of CT coronary angiograms (CTCA) for patients with low-risk chest pain refuse to fold. Despite the failure of major trials to demonstrate an advantage of CTCA over standard care and impassioned editorials questioning the fundamental insanity of their use, the American Heart Association (AHA) has issued new guidelines for appropriate cardiac imaging.7,8 Oddly, according to these guidelines, nearly every possible permutation of potential cardiac chest pain is deemed appropriate for CTCA, explicitly including even low-risk, troponin-negative patients with Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) scores of zero.

Even more damning, the authors of the AHA guidelines also endorse the so-called “triple rule-out” scan for cases in which a “leading diagnosis is problematic or not possible.” Considering the various conflicts of interest relating to imaging technology on the writing and rating panels, it’s not surprising the default recommendation is “don’t think, just scan.”

The right thing to do in medicine is rarely the easiest. Avoiding unnecessary admissions and CT scans requires communication and sharing uncertainty with patients, and such efforts require time we rarely have. Incentives—financial, medical-legal, and professional—only rarely align to support the highest-value practice of medicine. Nonetheless, we should continue striving to such ideals.

References

- Benayoun MD, Allen JW, Lovasik BP, et al. Utility of computed tomography imaging of the cervical spine in trauma evaluation of ground level fall. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016 Mar 30. [Epub ahead of print]

- Fesmire FM, Brown MD, Espinosa JA, et al. Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(6):628-652.e75.

- Stojanovska J, Carlos RC, Kocher KE, et al. CT pulmonary angiography: using decision rules in the emergency department. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(10):1023-1029.

- Menoch M, Simon HK, Hirsh D, et al. Imaging for suspected appendicitis: variation between academic and private practice models. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016 Apr 5. [Epub ahead of print]

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE. Use of computed tomography in emergency departments in the United States: a decade of coughs and colds. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):273-275.

- Greenslade JH, Parsonage W, Than M, et al. A clinical decision rule to identify emergency department patients at low risk for acute coronary syndrome who do not need objective coronary artery disease testing: the no objective testing rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(4):478-489.e2.

- Redberg RF. Coronary CT angiography for acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):375-376.

- Rybicki FJ, Udelson JE, Peacock WF, et al. 2015 ACR/ACC/AHA/AATS/ACEP/ASNC/NASCI/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR/SCPC/SNMMI/STR/STS Appropriate utilization of cardiovascular imaging in emergency department patients with chest pain: a joint document of the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria Committee and the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(7):853-879.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

No Responses to “Radiation Therapy Overuse Spikes in the Emergency Department”