Sex trafficking—as defined by the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000—is the “recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of an individual through the means of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of commercial sex.”1 In 2020, 7,648 cases of sex trafficking were reported to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, with the highest number of cases noted in California (1,334), Texas (987), Florida (738) and New York (414).2

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 04 – April 2022Health care settings are an important point of access for trafficked persons. In a study of 173 survivors of human trafficking, nearly 70 percent of individuals were seen by a health care worker while being trafficked; the ED is the most frequently accessed of these settings.3 The study sought to describe the health care settings most frequented by victims of human trafficking. Unfortunately, as many as 90 percent of sex-trafficked persons may go unrecognized by their physicians.4 Why do victims so frequently go undetected in the ED? This problem is due in part to medical staff often lacking the necessary training to identify trafficking victims and health care institutions rarely implementing standardized procedures to guide staff on the appropriate actions.

Recognizing Human Trafficking in the ED

An important first step in improving ED staff’s recognition and response to trafficking is implementing educational interventions. In fact, ACEP’s 2020 Policy Statement on human trafficking recommends that “emergency medical services (EMS), medical schools, and emergency medicine residency curricula should include education and training in recognition, assessment, documentation, and interventions for patients surviving human trafficking” and that “ED and EMS staff receive ongoing training and education in the identification, management, and documentation of human trafficking victims.”5 Many studies have shown that various formats—including didactic sessions, online modules, interactive workshops and case-based simulations—effectively increase ED staff’s baseline knowledge of sex trafficking and improve preparedness to identify and assist victims, but are infrequently identified.6–12 To address this issue, we developed and piloted a training intervention for physicians on human trafficking and how to identify and treat these patients. Included in the intervention participants were emergency medicine residents, ED attendings, ED nurses, and hospital social workers. Prior to the intervention, 4.8 percent felt some degree of confidence in their ability to identify and 7.7 percent to treat a trafficked patient. After the 20-minute intervention, 53.8 percent felt some degree of confidence in their ability to identify and 56.7 percent care for this patient population. Because this problem is global, we created a website that includes an instructive toolkit and an interactive course for self-learning and/or assessment. This intervention will give emergency physicians the tools they need to assess and treat a patient who might be a victim of human trafficking.5 Emergency physicians are on the frontlines of identifying and caring for trafficked persons. However, most emergency providers have never received training on trafficking, and studies report a significant knowledge gap involving this important topic. Workshops often employ a ”train-the-trainer” model to address clinicians’ knowledge gaps involving various topics (including trafficking).

Of note, most successful educational interventions were less than one hour long, suggesting that improvements are attainable even with time constraints. An important aspect of educational interventions is a focus on warning signs and symptoms that should alert emergency physicians to further investigate whether the patient may be a victim of trafficking. Examples of these warning signs include inconsistencies in one’s explanation of an injury, accompanying person speaking on behalf of the patient, signs of physical or sexual abuse, medical neglect, untreated sexually transmitted infections and/or excessively anxious behavior.13 These trainings should also emphasize the importance and application of trauma-informed care.

Once emergency staff has a foundational understanding of sex trafficking, the next step is to implement a standardized screening tool. Emergency physicians and nurses should utilize a screening tool any time they have a reason to suspect a patient may be in a trafficking situation; an understanding of potential warning signs is key as these red flags will alert the clinician to proceed with a formal screening. Importantly, the threshold for suspicion should be kept low to reduce the likelihood of missing a case of trafficking. Many screening tools exist, although they vary considerably in length and design. To date, two screening tools have been validated for use in the emergency department setting.

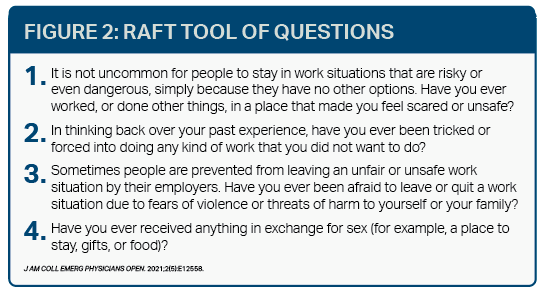

The Greenbaum Tool (see Figure 1) was developed specifically for use in pediatric emergency departments in patients between the ages 13 and 17.14

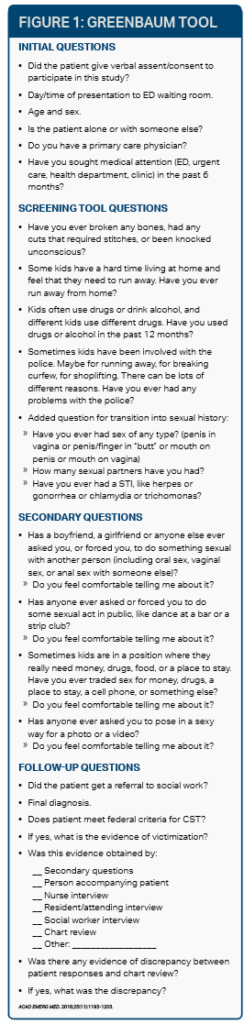

Rapid Appraisal for Trafficking (RAFT) tool (see Figure 2) was validated in 2021 for use in the adult ED patient population and is a comprehensive trafficking screening tool for use in health care settings.15 These screening questionnaires should be readily available to ED staff—either at the nurses’ station or embedded in the electronic medical record—or should be memorized and rehearsed for faster recall.

Setting Protocols in Place

When faced with a positive screen, ED staff may be unsure of how to best assist their patient. Thus, another crucial step to improve the care of trafficking victims is the implementation of standardized protocols. These protocols should integrate a screening tool with guidelines for the next steps to assist the victim. The HEAL Trafficking and Hope for Justice’s Protocol Toolkit is a great starting place for health care institutions to develop their own protocols.16 When developing a protocol, it is necessary to identify local organizations and services that can assist victims as the patient may have many immediate needs that need to be addressed including housing, medical follow-up, mental health services and substance use treatment. Moreover, these protocols will provide procedures to ensure the safety of the patient and staff as well as guidelines on when to involve outside agencies, such as local, state, and federal law enforcement and child protective services.

Figure 2: RAFT Tool of Questions

In the often-hectic environment of the ED, it is no surprise that sex trafficking victims so often slip through the cracks. However, there are feasible steps that can be taken to ensure ED staff are properly trained and have the necessary tools to identify and assist victims.

DR. POURMAND is director of digital media and professor of emergency medicine at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. MS. MARCINKOWSKI is a medical student at The George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences.

References

- Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. U.S. Department of State. .

- Hotline statistics. National Human Trafficking Hotline.

- Chisolm-Straker M, Baldwin S, Gaïgbé-Togbé B, et al. Health care and human trafficking: we are seeing the unseen. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):1220-1233.

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:61.

- Human trafficking. ACEP. 2020 Feb.

- Chisolm-Straker M, Richardson LD, Cossio T. Combating slavery in the 21st century: the role of emergency medicine. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):980-987.

- Cole MA, Daniel M, Chisolm-Straker M, et al. A theory-based didactic offering physicians a method for learning and teaching others about human Trafficking. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2(Suppl Suppl 1):S25-S30.

- Donahue S, Schwien M, LaVallee D. Educating emergency department staff on the identification and treatment of human trafficking victims. J Emerg Nurs. 2019;45(1):16-23.

- Egyud A, Stephens K, Swanson-Bierman B, et al. Implementation of human trafficking education and treatment algorithm in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2017;43(6):526-531.

- Harlow AF, Rothman EF, Dyer S, et al. EMS professionals: critical partners in human trafficking response. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(10):641.

- Ma K, Ali J, Deutscher J, et al. Preparing residents to deal with human trafficking. Clin Teach. 2020;17(6):674-679.

- Scannell M, Conso J. Using sexual assault training to improve human trafficking education. Nursing. 2020;50(5):15-17.

- Schwarz C, Unruh E, Cronin K, et al. Human trafficking identification and service provision in the medical and social service sectors. Health Hum Rights. 2016;18(1):181-192.

- Kaltiso SAO, Greenbaum VJ, Agarwal M, et al. Evaluation of a screening tool for child sex trafficking among patients with high-risk chief complaints in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(11):1193-1203.

- Chisolm-Straker M, Singer E, Strong D, et al. Validation of a screening tool for labor and sex trafficking among emergency department patients. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(5):e12558.

- Baldwin SB, Barrows J, Stoklosa H. Protocol toolkit for developing a response to victims of human trafficking. HEAL Trafficking and Hope for Justice; 2017.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Recognizing Human Trafficking Victims as Patients in the Emergency Dept.”