As discussed in previous issues, the availability of options for severe pain control other than opioids has increased as our understanding of the mechanisms of pain neurobiology has grown. Another area that has come into the spotlight, since the advent of ultrasound, has been the use of regional anesthesia for pain control or for procedures.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 04 – April 2015Initial use of ultrasound focused on its diagnostic utility with the development of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma, or FAST, exam—aortic aneurysm, intraperitoneal fluid, etc. That use has continued to expand, and ultrasound now can be used to diagnose congestive heart failure and even intravascular volume depletion by assessing the inferior vena cava.

Procedural uses for ultrasound have been, for the most part, limited to vascular access, peripheral or central, with only a few centers using ultrasound for regional anesthesia. This latter application should probably be the greatest use of ultrasound in our departments, not the least. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (UGRA) is not only extremely safe, but it guarantees block success.

Benefits of UGRA

Initial studies looking at regional anesthesia discussed femoral nerve blocks for hip fractures. Ultrasound was not used. Although the studies described success in pain relief, closer review described the onset of pain relief from the blocks taking hours. In other words, many of the reported blocks were, in fact, not successful; onset of pain relief should take five to seven minutes. For many nerves, use of anatomical landmarks (blind technique) can result in unacceptably high failure rates and possible complications. Use of ultrasound will markedly change that and provide proper regional anesthesia in most hands. Unfortunately, UGRA is not considered a priority. Even in a center where femoral nerve blocks were done, time to UGRA for femur fractures averaged two hours prior to the initiation of a specific protocol that targeted a time of 15 minutes after arrival.1 In another study of patients with flail chest injuries requiring ventilatory support, where regional anesthesia (epidural) is supposed to be the standard of care, only 8 percent of patients received an epidural.2

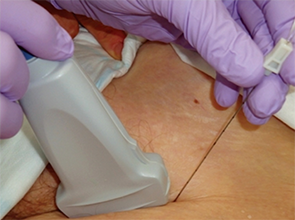

Figure 1. In plane approach for ultrasound guided block of the femoral nerve.

(click for larger image)

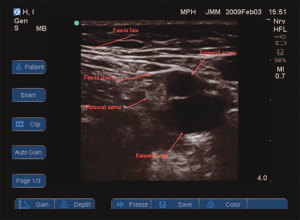

Figure 2. Ultrasound view of the anatomy of the left femoral triangle.Source: Anaesthesia. 2010;65(Suppl 1):57-66. Reprinted with permission.

UGRA allows not only visualization of the needle to the nerve, it also allows visualization of the anesthetic flowing around the nerve. It is also provides proof that the needle did not touch other structures (such as the lung, artery, etc.). The combination of success with a very high safety record is something we should always seek. UGRA can be an excellent alternative to procedural sedation in patients at risk (eg, an ASA 3 patient who may not tolerate sedation or a patient with altered mental status). In such patients, UGRA such as supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks or sciatic nerve block in the popliteal fossa allows for painless reduction of distal dislocations or fractures without the risks of sedation or the need for complicated monitoring.

UGRA should not be limited to procedures but should also be used for effective pain control. However, its limitations need to be understood. In patients at risk for the development of compartment syndrome, UGRA will hide the first and most important symptom of increasing pain. Such patients are therefore not candidates for UGRA. Regional anesthesia has to be integrated into trauma protocols if they are to become a routine part of practice. Currently, pain management is not considered a priority in the resuscitation of unstable trauma patients. It is often not a priority even in patients with isolated extremity fractures. The latter are routinely sent for imaging and confirmation of fracture before any pain control is administered. Introducing UGRA as part of a trauma protocol could be straightforward: Almost every trauma patient receives a routine ultrasound assessment. The machine is already at the bedside. Since ultrasound can rapidly identify long bone extremity fractures, couldn’t the logical next step be to move the probe a few inches and perform UGRA?

There are advantages to providing regional anesthesia over systemic analgesics. It allows ongoing assessment of the rest of the patient without impediment from systemic medications. Long-acting anesthetics such as bupivacaine or ropivicaine used within the first four hours after the injury can successfully block windup and minimize pain later and the need for analgesics down the road. Note that short-acting agents such as lidocaine cannot have this effect nor can systemic medications such as opioids or ketamine. In a 2003 study by Morrison et al, failure to effectively control pain from hip fractures in elderly patients increased ninefold the risk of deterioration of their mental status.3 Most of us have difficulty titrating opioids to a safe and effective endpoint in patients who are cognitively impaired. Use of UGRA guarantees complete pain control for at least six to eight hours. Placement of an infusion catheter using ultrasound ensures ongoing pain relief until a patient gets to the operating room.

Training and Uses

Proper technique is essential, so training must be arranged. Many universities now offer cadaver-based regional anesthesia courses, often targeting anesthesiologists and pain physicians, but the training is equally valid for us. Regional anesthesia with and without ultrasound should be an integral part of our practice.

Consider:

- Facial nerve blocks for laceration repair

- Occipital nerve block for laceration in the posterior half of the scalp

- Median nerve blocks or ulnar nerve blocks for hand injuries

- Suprascapular nerve block for shoulder reduction

- Epidurals for flail chest injuries (working with anesthesiology)

- Brachial plexus blocks for upper extremity injuries (or localized severe burns)

- Femoral nerve blocks for hip and femur fractures (see Figures 1 and 2)

- Sciatic nerve blocks for ankle or foot injuries and reductions

I am certain that many readers could identify other blocks they have found effective. This should be an integral part of our patient care and part of our core education.

Dr. Ducharme is editor in chief of the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine and clinical professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

Dr. Ducharme is editor in chief of the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine and clinical professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

References

- Johnson B, Herring A, Shah S, et al. Door-to-block time: prioritizing acute pain management for femoral fractures in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:801-803.

- Dehghan N, de Mestral C, McKee MD, et al. Flail chest injuries: a review of outcomes and treatment practices from the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:462-468.

- Morrison RS, Magaziner J, Gilbert M, et al. Relationship between pain and opioid analgesics on the development of delirium following hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:76-81.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Regional Anesthesia an Alternative to Opioids in the Emergency Department”