The best questions often stem from the inquisitive learner. As educators, we love and are always humbled by those moments when we get to say, “I don’t know.” For some of these questions, you may already know the answers. For others, you may never have thought to ask the question. For all, questions, comments, concerns, and critiques are encouraged. Welcome to the Kids’ Korner.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 08 – August 2016[/fullbar]

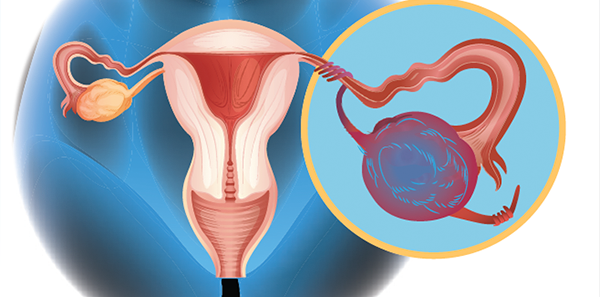

Question #1: “In children, is there an ovarian size (volume) that rules out torsion?”

About 15 percent of cases of ovarian torsion occur in childhood. Two peak times of occurrence exist: 1) within the first year of life, and 2) at menarche. This has lead some to speculate that ovarian volumes in the normal range may “rule out” ovarian torsion and some articles do find abnormally enlarged volumes in their ovarian torsion cases.1 Torsed ovaries are more commonly enlarged secondary to impeded venous return and edema that occurs after the initial torsion—prohibiting spontaneous detorsion.2 While it decreases the probability of ovarian torsion, it does not appear to definitively exclude ovarian torsion.

A retrospective study by Servaes et al evaluated sonographic findings of surgically proved cases of ovarian torsion in 41 patients over a 12-year period. The median age of patients with ovarian torsion was 11 years, with a range of 1 month to 21 years of age. The authors mention that torsion occurred in “otherwise normal ovaries without a potential lead point in 34 percent (14/41)” of patients. The authors found that the mean volume ratio was 12 times larger in the torsed ovaries compared to the contralateral ovaries. While the article makes the statement that “all torsed adnexa were larger than the normal contralateral ovary,” the data report that there was only one of 41 patients who had an enlarged ovary and adnexa.3 While these data appear slightly confusing, they do emphasize one important point: Comparing the patient’s contralateral (good) ovary may be helpful.

There were 10 contaminated samples and two true-positive blood cultures, neither of which changed antibiotics or medical management. The authors concluded that a “blood culture is not useful in the management of immunocompetent well-appearing children admitted for uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections, and its routine practice should be avoided.

A second retrospective study by Tsafrir et al evaluated 22 ovarian torsion cases over an 11-year period in premenarchal patients only. On surgical exploration, they found that the torsed ovary was not enlarged in 59.1 percent (13/22) of cases. Of the 22 cases, they performed transabdominal ultrasound with a full bladder on 20 of them, noting that there were “normal-sized ovaries with or without signs of edema in eight and four cases, respectively.”4 This means that 12 of 20 cases (60 percent) had a normal reported ovarian size. Specific measurements weren’t provided in this article, however.

Summary

While the data are very limited, there doesn’t appear to be a lower-limit volume that rules out ovarian torsion in children. Most cases of ovarian torsion demonstrate an enlarged torsed ovary, but a potentially large percentage of confirmed ovarian torsion cases have normal ovarian volumes. A comparison to the contralateral (normal) ovary size may be helpful.

Question #2: “In pediatric cases of uncomplicated cellulitis, are blood cultures necessary?”

One big difference between past pediatric literature and adult literature was the pediatric presence of Haemophilus influenzae (Hib), which commonly progressed to bacteremia. The traditional practice of obtaining blood cultures for cellulitis, though, was based in the pre-Hib era. In the post-Hib era, studies are slowly accumulating on this topic.

A study by Sadow and Chamberlain retrospectively evaluated 243 children who were admitted with cellulitis with or without an associated abscess. The population was 67 percent African-American, 16 percent Caucasian, and 11 percent Hispanic. Ninety-seven (97) percent were described as nontoxic. The authors looked at all causes and locations of cellulitis, both on the face and body, and found that 60 of 243 cases (24.7 percent) had an associated abscess. Blood cultures were positive in 18 patients (7.4 percent). Thirteen (13) were false-positives. Only five of 243 (2.1 percent) were true-positives. This meant they were 2.5 times as likely to have a false-positive blood culture as a true-positive result, and true-positive cultures grew either staph or strep. Only one blood culture led to a change in the patient’s antibiotic. The authors concluded, “Blood cultures are not cost-effective in the management of immunocompetent patients admitted for cellulitis.”5 While retrospective in nature, this study suggests that blood cultures rarely change medical management in a positive fashion.

Similarly, a study by Trenchs et al retrospectively evaluated blood cultures for uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections in admitted children. Cellulitis anywhere on the body was included, and blood cultures were drawn on 353 of 445 included patients (79.3 percent). Abscesses were involved in 78 (17.5 percent) of these cases. Like the prior study, false-positive culture results were more prevalent than true-positive results. There were 10 contaminated samples and two true-positive blood cultures, neither of which changed antibiotics or medical management. The authors concluded that a “blood culture is not useful in the management of immunocompetent well-appearing children admitted for uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections, and its routine practice should be avoided.”6 Other studies by Malone et al and Leonard and Beattie reported similar results, suggesting that blood cultures minimally affect clinical management and, more commonly, are false-positive.7,8

Summary

In cases of uncomplicated cellulitis in children with and without an abscess, multiple retrospective studies appear to suggest that blood cultures rarely affect clinical management and probably aren’t needed.

Dr. Jones is assistant professor of pediatric emergency medicine at the University of Kentucky in Lexington.

Dr. Jones is assistant professor of pediatric emergency medicine at the University of Kentucky in Lexington.

Dr. Cantor is professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics, director of the pediatric emergency department, and medical director of the Central New York Poison Control Center at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York.

Dr. Cantor is professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics, director of the pediatric emergency department, and medical director of the Central New York Poison Control Center at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York.

References

- Linam LE, Darolia R, Naffaa LN, et al. US findings of adnexal torsion in children and adolescents: size really does matter. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(10):1013-1019.

- Spinelli C, Piscioneri J, Strambi S. Adnexal torsion in adolescents: update and review of the literature. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;Oct;(27)5:320-5.

- Servaes S, Zurakowski D, Laufer MR, et al. Sonographic findings of ovarian torsion in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(5):446-451.

- Tsafrir Z, Azem F, Hasson J, et al. Risk factors, symptoms, and treatment of ovarian torsion in children: the twelve-year experience of one center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(1):29-33.

- Sadow KB, Chamberlain JM. Blood cultures in the evaluation of children with cellulitis. Pediatr. 1998;101(3):E4.

- Trenchs V, Hernandez-Bou S, Bianchi C, et al. Blood cultures are not useful in the evaluation of children with uncomplicated superficial skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(9):924-927.

- Malone JR, Durica SR, Thompson DM, et al. Blood cultures in the evaluation of uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-459.

- Leonard P, Beattie TF. How do blood cultures sent from a paediatric accident and emergency department influence subsequent clinical management? Emerg Med J. 2003;20(4):347-348.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

No Responses to “Research on Ovarian Size in Children Provides Guidance on Dealing with Torsion, Uncomplicated Cellulitis”