Providing support, treatment for acute flare-ups and new pain pathology, understanding medication requests, and avoiding adverse drug events are part of the ED mandate

The figures are well-established: more than a quarter of people will suffer from chronic pain during their lifetime. It is the disease state with the highest economic impact on society in terms of lost workdays. The average annual family income of patients with chronic pain is less than $25,000, which is below the poverty line. But why do emergency physicians need to know about chronic pain?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 01 – January 2014Few physicians among us understand the myriad of pain conditions that fall under the label “chronic pain.” Fewer still recognize the pathologic changes in personality associated with chronic pain as being part of the disease symptom complex, just as peripheral neuropathy is a manifestation of diabetes. Most family physicians are ill-equipped to provide the multidisciplinary care required; most patients cannot afford the paramedical care provided by physiotherapists, psychologists, social workers, etc. Pain management is further complicated by the issues related to opioids—opiophobia, diversion, and addiction—even though only one-third of chronic-pain patients require opioids as part of their care.

The consequence? Chronic-pain patients are poorly understood and poorly treated. As a result of not having their pain properly controlled and not having been taught adequate coping skills, these patients modify their behavior in an attempt to get the physician to provide the necessary care—aberrant behaviour called pseudoaddiction. Distinguishing aberrant behavior linked to pseudoaddiction from that associated with true addiction is difficult at best; it may take a pain-medicine expert months to identify the underlying reason for the aberrant behavior. It is almost never possible to do so in an isolated visit to the emergency department.

The emergency department is the safety net of our system—impoverished patients in pain receiving inadequate (or no) care from a primary-care provider have nowhere else to turn. In the Pain and Emergency Medicine Initiative (PEMI) study involving 18 academic centers across Canada and the United States, 20 percent of patient visits had chronic pain as the primary reason for their visit to the emergency department. That is the largest percentage of visits to the emergency department for any one pathology; paradoxically, it is decried by most emergency physicians as a condition that is “not part of emergency medicine.” It is clear the emergency department cannot provide ongoing care to chronic-pain patients any more than it can do so for patients with diabetes. It is equally clear that we must be involved in their care to some degree, just as we are involved to some degree in the care of many patients with a chronic disease—that is the nature of our horizontal specialty. What is our role?

Caring for patients with chronic pain is part of the ED mandate. Distinguishing them from patients with problems of addiction is difficult, but they are not the same patients and should not be treated similarly.

Acute Flare-up of Chronic Pain

Certain conditions, such as fibromyalgia (FM) or complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), generate new pain or acute worsening of that pain state. Our role is to first ensure that patients are not suffering from a new acute condition unrelated to their chronic pain condition—the latter does not make them immune to other pathology. Intervening with ketamine in analgesic doses can abort the acute flare-up in CRPS. For patients with FM, reassurance they do not have a new medical problem will usually result in their returning home satisfied, reluctantly accepting that their new pain is, indeed, part of their FM.

Acute New Pain Pathology

Patients who take medications for chronic pain (including opioids) require proper pain management just like everyone else when they suffer, for example, an acute fracture. If they already take opioids, they will require their usual daily dose plus dosing for their new pain; often, identifying what their usual PRN dose is will give a starting point for the first dose of opioids in the emergency department, with titration after that. Physicians have to recognize that the doses of opioids required to provide adequate analgesia in chronic-pain patients taking long-term opioids will almost always be higher than the doses we use for patients not taking such opioids.

Medication Requests

Patients receiving care from pain physicians require a minimum of two to three months to get their pain controlled. Emergency physicians should, therefore, not feel an obligation to provide or initiate a medication for someone’s chronic pain during a single emergency department visit, nor should they feel any urgent need to manage that chronic pain in the emergency department. Patients receiving long-term opioids have an agreement or contract with a primary provider wherein only that provider will prescribe their opioids. If patients were to go to their primary provider and say they had “run out” a few days early, the provider would reiterate that the patients are responsible for their medication usage and not renew the prescription until the next scheduled time interval. In the emergency department, the physician should restate this “single provider” principle and feel very comfortable declining to provide opioids, all the while offering to help patients in any other way possible.

Adverse Events or Drug-Drug Interactions

Most emergency physicians are unfamiliar with either the medications prescribed or the (high) doses prescribed for chronic-pain management. While most physicians will not exceed 75 mg of amitriptyline, for example, patients with neuropathic pain may require up to 250 mg. Higher than normal dosing carries a higher risk of adverse events. Another example of risk is seen in patients prescribed methadone for pain or addiction. These patients will have a markedly prolonged QT interval from the methadone. Multiple case reports of sudden death have been reported after patients taking methadone were prescribed a fluoroquinolone. It is critical during the emergency visit that we ensure patients will not suffer from such an adverse event.

Why is abnormally high dosing often required when medications are used to manage pain? For many patients in pain, their nervous system has undergone “plastification” as a result of the pain. Functional MRI often shows multiple areas of the brain with abnormal function. Be it the development of tolerance with opioids or the higher doses of non-opioid medications required to deactivate abnormal synaptic transmissions, patients with chronic pain often require dosing higher than what may be considered therapeutic for other conditions. These higher doses should not lead to suspicion of misuse or drug dependency but should lead to careful evaluation to identify possible adverse effects.

Providing Support

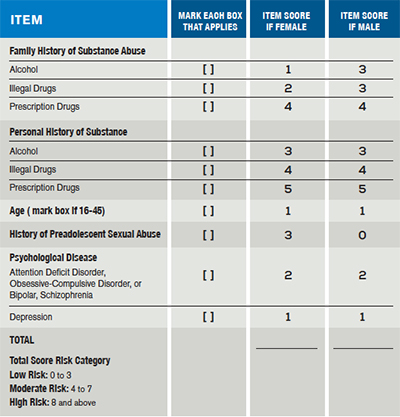

In chronic-pain patients who have been properly screened for addiction risk using the Opioid Risk Tool (see Table 1), the risk of addiction for those who are scored at low risk is less than 0.2 percent—60 times lower than the general public rate of addiction. When these patients arrive in our emergency departments, they do not know where else to turn. Simply saying “no” is not a solution. Guiding them to support services, advising them of community resources, demonstrating understanding, and educating them on the role of the emergency department in their care are all key roles for emergency physicians to play. We advise smokers to stop smoking and guide them to programs; we encourage alcoholics to get into detox programs; we advise diabetics about diet, exercise, and community programs—surely, we can do the same for patients with chronic pain.

Higher than normal dosing carries a higher risk of adverse events. Another example of risk is seen in patients prescribed methadone for pain or addiction. These patients will have a markedly prolonged QT interval from the methadone. Multiple case reports of sudden death have been reported after patients taking methadone were prescribed a fluoroquinolone.

Mandate for Care

Caring for patients with chronic pain is part of the emergency department mandate. Distinguishing them from patients with problems of addiction is difficult, but they are not the same patients and should not be treated similarly. They have very different needs because they suffer from very different pathologies. Learning more about chronic pain conditions will allow us to provide the necessary care.

Hands On: Chronic-Pain Management at McKesson Canada

As part of my role within McKesson, I directly oversee the running of nine community-based pain centers where patients with chronic non-cancer pain are treated. Unlike what is commonly thought, only one-third of the patients treated there received opioids as part of their care. The optimal approach to chronic-pain management is a combination of multidisciplinary clinical care, self-management programs to learn proper coping skills, medications, and nerve blocks (the last is effective in roughly 20 percent of all chronic-pain patients). Identifying patients with pain at risk for addiction is a key screening element and part of a 21-page initial evaluation tool completed by patients. In those patients identified as “at risk,” care pathways without opioids or with methadone are explored. Patient agreements are routine and include limiting patients to a single prescriber of opioids, no early renewals, and random urine drug testing (frequency determined by their score on the Opioid Risk Tool). All physicians have to undergo our standard training and be supervised for their first year of practice (provincial regulation) in pain management.

Jim Ducharme, MD, CM, FRCP, is editor in chief of the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, clinical professor of medicine at McMaster University, and chief medical officer of McKesson Canada.

Jim Ducharme, MD, CM, FRCP, is editor in chief of the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, clinical professor of medicine at McMaster University, and chief medical officer of McKesson Canada.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “The Role of Emergency Physicians in Caring for Patients with Chronic Pain”

January 26, 2014

jabenmJim

Very nicely done.

I never had the chance to thank you for weighing in on the ED pain management algorhythm I sent to Mel last year.

Mark

February 15, 2014

eleventy“In chronic-pain patients who have been properly screened for addiction risk using the Opioid Risk Tool (see Table 1), the risk of addiction for those who are scored at low risk is less than 0.2 percent”

That .2% is a great stat! Does anyone know where exactly it comes from?