Svetlana Zakharchenko, DO, an emergency physician in New Jersey, left Ukraine for the United States 30 years ago—the closest she can get now to her old homeland is a camp in Poland at the border to Ukraine. The medical tent where Dr. Zakharchenko volunteers prominently sits at the front of the refugee camp with a sign welcoming the tired Ukrainians: “We treat anyone and everyone.”

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 11 – November 2022Four months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing war as a volunteer in the refugee camps of neighboring Poland, Dr. Zakharchenko takes blood pressure, listens to lungs, treats immediate medical needs, and refills what medications she can from the donated supplies. After returning to the U.S., she sat down to document her experiences.

“What can you do?” she wrote, “When your patient tells you what hurts the most isn’t their chest or the bruise on their arm—when a patient tells you, ‘My soul hurts.’”

Take 16-year-old Vanya. Dr. Zakharchenko wrote:

“When Mariupol, his home city, came under attack, everyone thought the fighting would be brief and that the war would soon end—no one predicted what actually happened, with the city now destroyed and lying in rubble.

Ukrainian physicians practice ultrasound skills using donated Butterfly devices during MedGlobal’s POCUS training in Ukraine.

“The Russian military controlled all entry and exit points. Day after day, the bombing and fighting intensified, but when his mother still refused to leave, Vanya left without her. There were three waves of people leaving Mariupol. The first wave was mostly children, and they were allowed to pass. The second wave was stripped and searched, their belongings confiscated, but they, too, were allowed to pass. The third wave was shot. It took Vanya a week to reach Poland on foot, and in the freezing February nights, many of the other refugees died along the road. Now he’s stuck in limbo, waiting in the refugee camp without knowing what comes next.”

Dr. Zakharchenko spoke with each patient she treated, and the stories all echo with tragedy—one woman in particular, Angelina, stands out. Dr. Zakharchenko writes:

“When the bombing started in Kharkiv, Angelina tried hard to maintain a sense of normalcy. Even as hospitals were shut down and whole neighborhoods disappeared in a pile of stones, caved in roofs, and cratered streets, Angelina and her husband went on a walk every day. At night, they were kept from sleeping by the constant shelling and rapid gunfire, tactics used by the Russians to instill fear in the civilians. There were power outages and food shortages, and people died at home from treatable conditions because the ambulances couldn’t reach them. Angelina and her husband persevered through all of it, but when a bomb fell so close to them that their daughter was almost lifted out of the stroller, they knew they had to leave.”

Across the border and in the heart of Ukraine, the refugee situation is no better. School gymnasiums and classrooms, monasteries, fitness studios, and other storefronts have all been re-appropriated to house the ever-growing number of refugees fleeing eastern Ukraine for the relative safety of western Ukraine. Tanya Bucierka, DO, an emergency physician from Oregon with deep Ukrainian roots, has made the perilous journey across the border by bus twice already, with plans for a third trip this fall.

“It’s a lot of primary care, but more than headache cures or blood pressure medications, many of the patients just want someone to hear their stories,” Dr. Bucierka said. “They may be resilient, but they’re still traumatized.”

She remembers meeting Petro, a Russian-speaking refugee who lived in Luhansk in eastern Ukraine. A hacking, wet cough interrupted him whenever he tried to speak—after spending a month underground in a bomb shelter, hardly ever venturing above ground, his untreated respiratory symptoms sounded suspiciously like pneumonia. When Petro and his wife Anna finally fled Luhansk, they had to dig their car out of the debris, finding that everything was covered in ashes. Anna, who had similar symptoms, minimized it as a simple chest cold and at first refused the medication offered.

“The soldiers on the frontlines need it more than us. Send it to them,” she said, apologizing for speaking in Russian. She and Petro are Ukrainian but don’t speak the language—it never seemed important before, but now they are taking a free class, trying desperately to learn. The war forced them from eastern to western Ukraine, but no matter how much the fighting intensifies, they are determined to flee no further. “This is our home.”

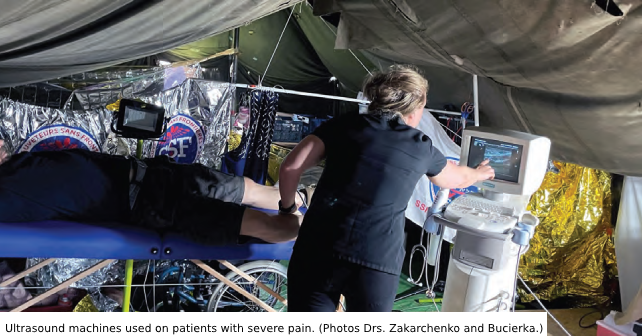

When Dr. Bucierka is not braving the road in a car heaped full of donated medical supplies to make rounds among the refugees, she can be found in the local medical university’s simulation lab, where she teaches point of care ultrasound to a group of Ukrainian doctors while in another classroom her surgical colleague demonstrates trauma surgery techniques on pig cadavers. Before the war, many civilian physicians had limited experience with trauma medicine. The Ukrainian emergency physicians learn eFAST, cardiac, ocular, and musculoskeletal ultrasound exams, cramming years of knowledge into a few short days so that they can return to the frontlines, bringing the new techniques—and the new donated ultrasound machines—with them.

At the end of the day, one of the Ukrainian doctors pulled Dr. Bucierka to the side. “This is the first time that war hasn’t been on my mind,” she said. “The first time that I’m enjoying medicine again with my friends and colleagues. Thank you.”

During their trips, both Dr. Zakharchenko and Dr. Bucierka have come to understand that medicine is as much an art as a science. What many of the Ukrainians need isn’t only food, shelter, medicine, or even skills—they also need someone to listen.

Ruminating on this, Dr. Zakharchenko wrote, “There is no perfect way to respond to disaster and war. There is no perfect way to address suffering, except to be present for those in need. What was once unthinkable has become a reality for millions of Ukrainians.” At the border, both Dr. Zakharchenko and Dr. Bucierka encountered stories of incredible loss—but also stories of resilience, hope, and courage. “We cannot heal all wounds,” Dr. Zakharchenko noted, “but sometimes listening and carrying those stories with us—both the good and the bad—is a first step toward peace.”

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Stories from the Ukrainian War: How Doctors and Refugees are Surviving”