A problematic manuscript regarding the “work-up” of strangled patients, authored by Zuberi et al. and published in 2019 by the journal Emergency Radiology, has recently come to our attention.1 This manuscript downplays the risks for traumatic dissection of the arteries of the neck caused by strangulations, which can lead to a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or “stroke.”

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 06 – June 2022If a consultant radiologist cites the findings of Zuberi et al., while attempting to dissuade the emergency physician from obtaining indicated computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck for a strangled patient, our summary could assist the emergency physician to capably refute that radiologist’s assertions and persuade them to perform the indicated testing. Our rationale centers not only upon the science of the matter, but also upon the risk for failing to meet the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) statute regarding the detection and stabilization of an emergency condition.

A strangulation typically occurs when forces are applied circumferentially around or focally to the neck, often by use of the hands and/or forearms, or via a ligature. Patients who have suffered strangulations that do not cause hyoid fractures or immediate airway compromise typically present to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and management. (The term “choking” should be reserved for instances in which a cough or gag reflex occurs due to defective swallowing, causing temporary and/or partial blockage of the trachea.)

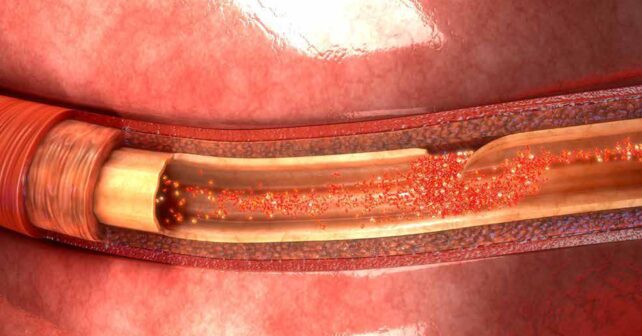

Emergency physicians are all too aware that many strangulations occur in the setting of domestic violence, and not all strangled patients show obvious initial signs of their injuries.2,3 Strangulations can acutely compromise arterial flow to or venous drainage of the brain, resulting in temporarily insufficient cerebral perfusion, which can cause unconsciousness or incontinence. Except for an acute or delayed airway emergency, the “worst-case” scenario for a patient who has been strangled and survived the attack is to have developed an intimal tear, causing an arterial dissection that can lead to a subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA).4 Such intimal tears are more likely when strangulation has involved digital compression of a carotid artery or vertebral transverse process. Tears and dissections may also follow “chokeholds” as used in martial arts and in some police-applied restraints, where sudden, forceful cervical twisting and/or stretching has occurred.

An “expert consensus” from the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention (TISP) exists regarding which history and physical examination findings suggest a significant risk for an arterial dissection.5 The 11 clinically-reasonable high risk criteria cited by the TISP include a transient loss of consciousness while being strangled, visual changes such as “flashing lights” or “tunnel vision,” intraoral, facial, or conjunctival petechiae, contusions or ligature marks to the neck, tenderness to palpation near the carotid artery, incontinence of bowel or bladder, new neurologic symptoms, dyspnea, dysphonia, odynophagia, and/or subcutaneous emphysema.5

However, this expert consensus to predict who will not harbor a dissection was not informed by statistical modeling (as today’s clinical prediction tools are).6 The risk factors cited by the TISP are qualitative and their relative contributions to prediction of risk for CVA have not been quantified.

Further, an emergency physician’s general obligation under the EMTALA statute is to evaluate the patient with a sufficient index of suspicion toward the detection of any emergency condition that might be present, to diagnose such conditions when they have occurred, and to render or refer elsewhere for appropriate definitive care.7 The EMTALA statute does not shield consultant radiologists from financial penalties when their clinical choices contribute toward a violation. The fact that arterial dissections after strangulation have a low likelihood does not matter. A low likelihood, in a condition with such devastating potential, does not imply that such outcomes have no likelihood.

Therefore, when emergency physicians evaluate strangled patients, one of the principal questions to be addressed, once it is clear that no airway emergency exists, is whether or not they are caring for that rare patient who harbors an arterial dissection and requires timely anticoagulation treatment to prevent an ischemic CVA.

To add clarity to this dilemma, Zuberi et al., prospectively assembled a cohort of 142 patients who endured strangulation and presented for emergency care at a single site over seven years.1 The initial readings of the angiograms obtained for these patients suggested six of the 142 patients harbored a vascular injury. Several of these initial readings were changed after review. Once these retrospective reviews of the angiograms were complete, four patients were determined to have a significant vascular injury. This included three with initial “true positive” findings, three with “false positive” findings, and one with an initial “false negative” finding. Unfortunately, the authors then dismissively concluded, “Performing CTA of the neck after acute strangulation injury rarely identifies clinically significant findings, with vascular injuries proving exceedingly rare.”

First, we believe that this conclusion may lead radiologists to under-estimate the degree of need and urgency present when emergency physicians order angiographic testing of strangled patients. The authors should not have downplayed the importance of the relatively few positive tests. Second, Zuberi et al. also failed to note the radiologists’ general obligations and risk for financial penalties if they are judged to be in non-compliance with the EMTALA statute. Third, they should have noted not only the non-zero probability for a dissection, but also the discordance between the initial and final reading of the angiograms. This could have led to advocacy for a period of observation that would enable angiograms to be over-read before the patient left the emergency department.

Zuberi et al., also raised concerns about radiation exposure from CTA of the neck, toward justifying a denial of a request for such imaging.1 We have not found data regarding the lifetime risk for cancer as a consequence of neck CTA, but the lifetime cancer risk of CTA imaging of the head has been estimated as 26 per million patients, or .0026 percent.8 In contrast, four significant vascular injuries were observed among the 142 patients studied. Thus, the prevalence of a significant vascular injury was 2.8 percent, which is three orders of magnitude greater than the approximate estimated risk of subsequent death due to radiation exposure. We believe most patients would accept this risk of angiography, because subsequent prevention of a stroke after heparinization would favorably impact their quality of life.

In fairness to the authors, we commend them for their persistence in studying this rare disease. Zuberi et al. required more than seven years to accrue their 142 patients at a single Level 1 trauma center, because relatively few of these patients present each year.

Also, the authors attempted to identify strongly predictive history or physical examination clues toward the diagnosis of vascular injury. However, their predictive efforts were doomed from the start, given the approximately three percent prevalence of vascular injury among patients. Generally, if a highly accurate clinical predictive rule is to be derived, one needs at least 10 patients with the disease for which testing is done per each step or element in the rule.9 Thus, if a rule has four predictive variables, one needs at least 40 patients with a dissection to have been included in the study. With a prevalence of dissections in the range of three percent, this would require enrollment of 1,333 strangled patients. If all of the 11 variables in the TISP’s guideline were represented in a rule, the authors would have needed to enroll more than 3,600 patients. Clearly, to assemble a sufficient cohort of patients to enable development of a clinical prediction rule would have required many more patients than Zuberi et al., could possibly have enrolled.

While we salute Zuberi et al., for their achievement of assembling their sizable case series, we find fault with the interpretation of their findings. Emergency physicians should not let themselves be persuaded against ordering appropriate angiographic imaging of strangled patients by the authors’ relatively low frequency of detection of significant findings.1 Emergency physicians should gently remind radiologists of their mutual obligations under EMTALA, as well as their ethical duty to the patient, when they press for the provision and performance of appropriate post-strangulation angiographic imaging, even if the radiologist attempts to dissuade.

Key Takeaway

If you believe your strangled patient deserves angiography to determine whether an arterial dissection is present, order the test in confidence that you are doing the right thing. If the radiologist tries to dissuade you, and especially if they cite Zuberi et al., remind them of the perspectives we have offered and place special focus upon your mutual obligations under the EMTALA statute.

Dr. Gaddis is a former professor of emergency medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo.

Dr. Green is a forensic consultant at the California Clinical Forensic Medical Training Center.

Dr. Riviello is professor and chair of Emergency Medicine at UT Health San Antonio.

Dr. Weaver is clinical professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri.

References

- Zuberi OS, Dixon T, Richardson A et al. CT angiograms of the neck in strangulation victims: Incidence of positive findings at a level one trauma center over a seven-year period. Emergency Radiology 2019;26:485-92.

- Strack, G. B. How to improve your investigation and prosecution of strangulation cases. National Family Justice Center Alliance, 2007. https://vawnet.org/material/how-improve-your-investigation-and-prosecution-strangulation-cases. Accessed September 25, 2021.

- Strack, G.B., McClane, G.E., Hawley, D. (2001). A review of 300 attempted strangulation cases: Criminal legal issues. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:303-309.

- Malek AM, Higashida RT, Halbach VV et al. Patient presentation, angiographic features and treatment of strangulation-induced bilateral dissection of the internal carotid artery. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:481-7.

- Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention. Recommendations for the medical/radiographic evaluation of acute adult, non-fatal strangulation. www.strangulationtraininginstitute.com Accessed September 24, 2021.

- Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD et al. A study to develop clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1992 Apr;21:384–390.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EMTALA Accessed September 25, 2021.

- Malhotra A, Wu X, Chugh A et al. Risk of radiation-induced cancer from computed tomography angiography use in imaging surveillance for unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Stroke 2018;50:76-82.

- Strobl C, Malley J, Tutz G. An introduction to recursive partitioning: Rationale, application and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging and random forests. Psychol Methods 2009;14: 323-48.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “It’s OK to Order Angiography Tests for Strangulation Victims”