1.All Superficial Venous Thromboses Are Created Equal?

Explore This Issue

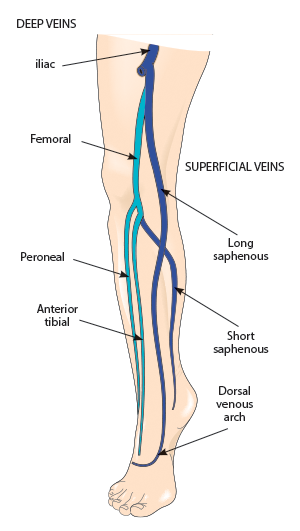

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 01 – January 2017Figure 1: Deep and superficial veins

Credit: SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

It is very easy to take the ultrasound report at face value and treat superficial venous thrombosis (SVT) as a benign entity distinctly different from deep venous thrombosis (DVT). However, that reasoning may result in missed or delayed diagnosis of DVT or inadequate treatment of at-risk patients. The belief that SVT is benign and DVT is potentially serious is an oversimplification of the disease process. The fact is that venous thrombosis is a continuum, and SVT and DVT are directly linked and not distinctly different. The key is in the location of the clot and the patient’s risk profile. Emergency physicians, and patients, can be victimized by limited data on an ultrasound report. All SVTs are not created equal. It’s just like real estate—location, location, location.

In an enlightening review article, Litzendorf and Satiani report that the incidence of DVT from SVT ranges from 6 percent to 40 percent (those with a history of prior DVT) and that the incidence of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) associated with SVT ranges from 2 percent to 13 percent.1 In short, an isolated distal lesser saphenous vein SVT is not the same as one at or approaching the saphenopopliteal junction or, worse, the saphenofemoral junction (see Figure 1). Despite the usual limitations of a review article, it provides some nice insight into recognition of those at risk for clot propagation and development of DVT or even PE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and heat are probably fine for inconsequential SVTs. However, systemic anticoagulation (just like a DVT), repeat ultrasound to look for propagation, and investigation of risk factors (eg, prior DVT, a history of malignancy, the presence of varicosities, and hypercoagulable disorders [up to 35 percent of patients with SVT]) are important considerations with a precariously placed proximal SVT. This article provided a nice flowchart (see Figure 2), prompting treatment options based on several factors. Concomitant DVT is also common. Binder et al, in a prospective, observational study, noted that in 46 consecutive patients with SVT, 24 percent had concomitant DVT, with 73 percent in the affected leg, 9 percent in the contralateral leg, and 18 percent in both legs.2

There is no single right answer because so many variables may impact the treatment plan. However, recognizing the significance of proximal SVT, compared to other locations, and considering concomitant DVT are critical to ensuring a good outcome.

Figure 2: Management plan for superficial venous thrombosis of the lower extremity.

Abbreviations: DVT, deep venous thrombosis; SFJ, saphenofemoral junction; SPJ, saphenopopliteal junction.

Reprinted from Litzendorf ME, Satiani B. Superficial venous thrombosis: disease progression and evolving treatment approaches. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2011;7:572 with permission from Dove Medical Press Ltd.

2. tPA and Intracranial Aneurysms, an Explosive Mistake?

Notwithstanding the momentum toward giving more tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to patients with ischemic stroke, safety and patient selection are of utmost importance. Controversy remains regarding the overall safety and efficacy of this treatment. However, certain assumptions about safety have been made that are not supported by the literature. “You would have to be out of your mind to give tPA to someone with a known intracranial aneurysm” seems like a reasonable statement. However, the fact of the matter is that tPA doesn’t make aneurysmal rupture more likely, and most people will die with their intracranial aneurysm (ICA) and not from it. Of course, if the aneurysm has already ruptured or a sentinel bleed has occurred, tPA would be a really bad idea.

Goyal et al investigated this issue and noted some surprising findings.3 Knowing the numbers of patients with ICA receiving tPA would be small, they created two components for their study. The first was a multicenter, prospective, observational study of 1,398 patients with acute ischemic stroke who received IV thrombolysis and also had neuroimaging, and the second was a meta-analysis combining the data from the first component with five other studies. In the first observational trial, 3 percent of patients had unruptured ICAs. There was one known case of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), but it was not associated with an ICA. In phase two, the meta-analysis of 120 patients, 6.7 percent experienced symptomatic ICH, and the relative risk was not impacted by the presence or absence of unruptured ICA. Although the numbers are small, they probably always will be. When it comes to tPA and ischemic stroke, proceeding with caution is always recommended. However, the presence of an ICA should be seriously considered and, of course, the patient informed of its presence, but it is not an absolute contraindication to tPA administration.

3. Glucose: If It’s High, Treat It?

Patients frequently present to the emergency department with incidentally elevated glucose levels. The question is, do we need to react to and treat every abnormality we see? The answer, in my opinion, is no. If an elevated glucose is merely an incidental finding and not a cause or contributing factor of the presenting condition or complaint, then perhaps we should resist the temptation to treat it—just note it and move on. I think we have come full circle on asymptomatic hypertension in the emergency department. Perhaps it’s time to do the same with incidental hyperglycemia.

Johnson-Clague et al evaluated 161 patients in a retrospective cohort study in an academic emergency department.4 Diabetic adults with a glucose of greater than 200 mg/dL were treated with subcutaneous insulin. Their glucose was measured 24 hours after discharge. Whether the glucose was above or below 200 had no apparent impact on hospital length of stay.

However, not everyone agrees. A 2011 article from Munoz et al reported a reduced hospital length of stay in ED patients who received subcutaneous insulin every two hours until their glucose was below 200 mg/dL (3.8 days versus 5.3 days).5 However, the intervention group of only 44 patients who all received insulin was compared to a historical control group in which only 35 percent received insulin. In addition, despite the difference being statistically significant (P <0.05), this is not clinically significant because the primary reason for admission was more likely the driver for length of stay than the patient’s glucose level.

In a recent study by Driver et al, a retrospective cohort chart review of 422 patients was performed and included only patients who were discharged and had a glucose level of equal to or greater than 400 mg/dL at some point during their ED visit.6 The mean arrival and discharge glucose levels were 491 mg/dL and 334 mg/dL, respectively. Seven percent (36 patients) returned for hyperglycemia and were admitted within seven days. However, after adjusting for several variables, including arrival glucose and the amount of insulin received, the discharge glucose was not associated with return ED visits or hospitalization for any reason.

Although all of these studies have limitations, we are comparing them to the physiologic argument that reducing elevated glucose must be a good thing. It’s time to stop a practice that seemed to make reasonable sense but has no proven benefit.

References

- Litzendorf ME, Satiani B. Superficial venous thrombosis: disease progression and evolving treatment approaches. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:569-575.

- Binder B, Lackner HK, Salmhofer W, et al. Association between superficial vein thrombosis and deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(7):753-757.

- Goyal N, Tsivgoulis G, Zand R, et al. Systemic thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurology. 2015;85(17):1452-1458.

- Johnson-Clague M, Dileo J, Katz MD, et al. Effect of full correction versus partial correction of elevated blood glucose in the emergency department on hospital length of stay. Am J Ther. 2016;23(3):e805-e809.

- Munoz C, Villanueva G, Fogg L, et al. Impact of a subcutaneous insulin protocol in the emergency department: Rush Emergency Department Hyperglycemia Intervention (REDHI). J Emerg Med. 2011;40(5):493-498.

- Driver BE, Olives TD, Bischof JE, et al. Discharge glucose is not associated with short-term adverse outcomes in emergency department patients with moderate to severe hyperglycemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(6):697-705.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Superficial Venous Thromboses, Intracranial Aneurysms, and Treating High Glucose Levels: More Myths in Emergency Medicine”