A few statistics that help to frame our hospital capacity crisis today: Immediately following World War II, the population of the U.S. was 144 million and there were more than 1 million inpatient hospital beds. Today, the U.S. population has more than doubled to 336 million, but hospital beds have been reduced to 917,000. Simply put, there are not enough inpatient beds in this country.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 03 – March 2024Prior to 2020, the problem of boarding, the holding of admitted patients in the emergency department (ED), was beginning to show signs of being managed. The Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) had noted that pre-pandemic boarding, captured and measured as Admit Decision to Departure (ADD) time, was trending downward.1 Many hospitals and EDs during the pandemic actually got a brief reprieve in terms of their volumes. Most however are now seeing their volumes roaring back alongside the concomitant return of extreme levels of boarding. To the horror of the front-line doctors and nurses, these extreme boarding conditions come with all of the poor outcomes and sequelae we expect to accompany hospital boarding in the ED.2-5

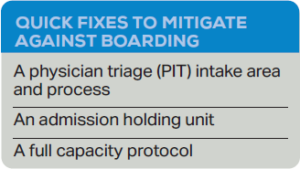

There are several quick fixes that can mitigate boarding. Two are in the front end and two in the back end. The first fix in the front end allows EDs of all sizes to continue to manage patients, even when much of the department’s real estate and resources are given over to the care of admitted patients. This initiative involves creating a Physician in Triage (PIT) model or more accurate nomenclature would be a “Physician Intake” area.6-8 PIT initiatives have been found to reduce wait times to see the physician, reduce walkaways, increase patient satisfaction and improve the quality of care for patients with time-dependent conditions.9-12 PIT is no longer a fringe idea. Many consider it a best practice, and the majority of moderate- to high-volume EDs in the U.S. employ a variation of this process.1

There are several quick fixes that can mitigate boarding. Two are in the front end and two in the back end. The first fix in the front end allows EDs of all sizes to continue to manage patients, even when much of the department’s real estate and resources are given over to the care of admitted patients. This initiative involves creating a Physician in Triage (PIT) model or more accurate nomenclature would be a “Physician Intake” area.6-8 PIT initiatives have been found to reduce wait times to see the physician, reduce walkaways, increase patient satisfaction and improve the quality of care for patients with time-dependent conditions.9-12 PIT is no longer a fringe idea. Many consider it a best practice, and the majority of moderate- to high-volume EDs in the U.S. employ a variation of this process.1

Example of a PIT, or physician intake area, space at a hospital.

When boarding is prevalent in a department, the physicians caring for those boarders will likely have the capacity to see new patients. The physicians have capacity (meaning time, medical knowledge and energy) but no place in which to see new patients. By creating a properly resourced intake area, arriving patients can continue to be seen and managed by physicians.

A PIT area (or physician intake area) typically needs an exam space with an exam table or stretcher, a computer for documentation and order placement, a workspace for an ED Technician to take vital signs and draw blood, supplies for this front-end work (i.e., phlebotomy and urine collection) and a waiting area for vertical patients to wait for test results. Some PIT models have a small medication-dispensary system for limited medication administration.

Patients identified as needing to be horizontal are brought back to the main department as quickly as possible. However, the majority of patients arrive ambulatory and can in fact remain vertical. The physician can begin the patient encounter and diagnostics from this intake area, even if the patient then backflows into the waiting room. Patients can be assigned beds later and their care assumed by a physician in the back. Some patients may have a discharge from the front end. No matter how you choose to design your patient flow, patient care must have clear ownership. The best of these PIT models will identify an internal waiting room (which may be chairs along a hallway) for patients who have seen the PIT doctor. When that is not possible, part of the ED lobby can be cordoned off as a “Results Waiting” area using signage and perhaps theater rope.

This ad hoc PIT process is not optimal. We should all agree that we prefer to avoid delivering care in the waiting room. That said, this is becoming a survival tactic for many EDs. It allows patients to receive care when the department’s treatment spaces are all occupied by boarders. This process can be “turned on” in EDs of any size, whenever capacity does not match demand in terms of space. If there are physicians able and willing to see new patients, the model will be successful and shorten the length of stay for patients overall. For EDs with an existing PIT process in place, it can be expanded by adding an extra physician or opening the model for more hours in the day when boarding is extreme.

The ED at Sentara Leigh Hospital in Norfolk, Virginia (70,000 visits per year) turns a variation of the PIT model on during periods of high census. Teams including a physician will rotate to the PIT area and “swarm” patients (typically three or four patients in a row). The team begins the patient encounter, ordering tests and treatments. As beds become available in the back, patients are brought to rooms in their original team’s zone. They arrive with testing already begun. In this way the Sentara Leigh ED guarantees that every patient in the waiting room has an assigned physician and a care team. This is essential in the present-day ED with a high-risk boarding burden: Physicians and staff must own and manage the waiting room. The front end is ours. At Sentara they discovered that in this model, physicians are motivated to make disposition decisions in a timely manner to make room for their other newly arriving patients still waiting in the waiting room. With the implementation of this model, Sentara Leigh reduced their door-to-physician times and their walkaways by more than 50 percent.13

It is important to note that sending a physician alone to the waiting room without proper resources is a failed tactic.

The physician in the waiting room has no capability to begin the workup and treatments without the right resources. By creating a PIT that is properly staffed and resourced, the diagnostic and treatment phase of the ED encounter can actually begin. Many patients have results posted by the time they are taken to their rooms, making a final disposition quick and efficient.

A second quick fix in the front end that is worth considering in 2024 is the Behavioral Health Team (BHT) program implemented at Lancaster General Hospital (LGH).14 This innovative process helps a department to address the surge of behavioral health patients now presenting in a post-pandemic tidal wave to EDs across the country. With an extraordinarily large waiting room as part of their footprint, the LGH ED was able to create a space for the BHT to evaluate mental-health patients in the front end. Many patients did not need to go back to the main emergency department or even occupy a room. With the exception of regional psychiatric receiving hospital EDs, the percent of all patients presenting with acute psychosis, mood disorders, drug abuse and detox, and suicidality is approaching 13 percent, but only a small and variable fraction of these patients need inpatient care.15,16 The BHT had a small unit established in the waiting room using room using dividers, a desk and lounge chairs. From here the majority of patients were screened, treated and discharged with outpatient referrals. If the patient needed a medical issue addressed, the PIT physician (who was working in an adjacent area) was able to easily drop in to assist the BHT to write a few orders or do a quick medical clearance. These are two of the few quick fixes open to an ED, which use ED resources to continue patient flow when the department is struggling with crushing levels of boarding.

Two additional quick-fix tactics involving the back end are not really new:

- the Admission Holding Unit and

- the Full Capacity Protocol

The former involves dedicating a space (within, adjacent to or outside of the main ED) where admitted patients are localized and managed with special policies and procedures.17 Increasingly, these admitted patients are being managed by inpatient teams. The latter quick-fix strategy was introduced some 20 years ago by Peter Viccellio, MD, FACEP, at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, New York. It quite simply involves moving patients from the ED hallways to upstairs inpatient hallways. Using very clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, patients being admitted to floors (not intensive care units) are systematically placed in the hallways adjacent to their designated rooms. The inpatient teams assume care for them while they wait for their assigned beds to be vacated and cleaned. Miraculously, these tasks are seen to occur more expeditiously when the inpatient team is now face-to-face with their newly admitted patient. Its success has been repeated wherever it has been introduced.18

A Primer on Boarding for the ED Physician

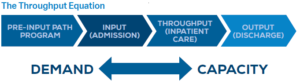

While the problem of boarding plays out in the ED, the real solutions to boarding are on the inpatient side and they are not simple. They often require culture change along with sweeping operational changes. The emergency physician ought to have some understanding of the basics of hospital boarding and its hospital-side solutions. The problem of boarding is due to a demand-capacity mismatch.19 This is most notably related to high census combined with inpatient discharge delays.20,21 Thirty years ago hospitals often operated at less than 90 percent capacity. In this new era of capacity constraint many large hospitals operate at 110 percent capacity or higher, with the continual boarding of inpatients in the ED and post-op spaces. For every patient being discharged there is already a patient waiting to take their place. If the discharge is delayed that patient remains in limbo, ergo boarding in the ED.

By day of the week and hour of the day, most hospitals are in a state of perpetual disequilibrium. Admissions outpace discharges; and then on weekends there is a catch-up phenomenon.

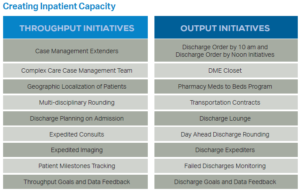

Demand is so tight relative to capacity that any delay in discharging a patient translates into boarding. Innovative hospitals have been addressing disequilibrium by focusing on the capacity side of the equation, creating or optimizing capacity one initiative at a time.

Most tactics that provide remedies to alleviate boarding do so by creating or recovering inpatient capacity. They do this by either improving throughput or addressing discharge delays.22-30 Much work has been done by hospitalists, who are now the largest admitting service at most hospitals (and the majority of patients boarding in the ED are general-medicine admissions). The emergency physician should have a passing knowledge about the remedies and inpatient best practices for throughput and discharge.

Unfortunately, pent-up demand for health care services deferred during COVID-19 has wiped out the capacity gains that hospitals had been making. A profound capacity crisis is afoot, and most EDs are experiencing boarding levels never seen before. Stakeholders are exploring any tactics to further address or mitigate boarding. Attention is shifting to the demand side of the equation, with a focus on “avoidable admissions.”31,32 Avoidable admissions for a group of diagnoses known as ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC) are thought to be preventable. With the provision of timely and effective ambulatory-care services, many conditions can be treated as outpatient illnesses and the hospitalization avoided.

Unfortunately, pent-up demand for health care services deferred during COVID-19 has wiped out the capacity gains that hospitals had been making. A profound capacity crisis is afoot, and most EDs are experiencing boarding levels never seen before. Stakeholders are exploring any tactics to further address or mitigate boarding. Attention is shifting to the demand side of the equation, with a focus on “avoidable admissions.”31,32 Avoidable admissions for a group of diagnoses known as ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC) are thought to be preventable. With the provision of timely and effective ambulatory-care services, many conditions can be treated as outpatient illnesses and the hospitalization avoided.

One roadblock to this work is ideologic and comes from our collective understanding of the specialty of emergency medicine. Emergency physicians have always prided themselves on providing whatever the patient needs in the moment, treating both emergencies and urgent unscheduled conditions. Now in this era of capacity crisis the specialty has met a new reality. Health care does not have infinite capacity. Health care delivery is a zero-sum game; if patient A receives a service it will not be available to patient B simultaneously. While health care delivery may not need rationing, it certainly needs sequencing and scheduling. This has led front-line emergency physicians to return to the demand side of the throughput equation.

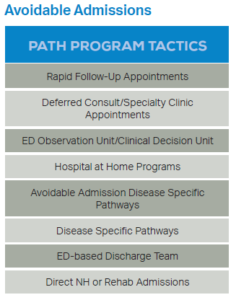

This “avoidable admissions” movement to reduce demand for inpatient hospital capacity from the ED is sometimes dubbed the practical alternatives to hospitalization (PATH) movement.33-35 Studies vary in how much this demand can be reduced, but this new and growing body of literature suggests that tactics can reduce avoidable admissions by 10 to 40 percent.

The avoidable admissions tactics can include a number of processes, initiatives and programs. Avoidable admissions can be addressed using an array of interconnected strategies:

- Rapid follow-up appointments: A number of studies have shown that when there are timely follow-up appointments for ED patients, then avoidable admissions can be managed effectively.36-38 Even next-day follow-up phone calls to check on discharged ED patients can help reduce admissions.39

- Deferred consultations or subspecialty appointments: One study from Norway recorded that 14 percent of ED admissions were due to a need for subspecialty consultations. The same study estimated that 21 percent of these subspecialty admissions could have been avoided.40 This is leading to efforts at improving care transitions through patient navigation and efficient centralized scheduling to avoid those admissions of stable ambulatory patients in need of subspecialty care.

- ED observation unit (EDOU) or clinical decision unit: In another prospective survey of emergency physicians, reported in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine by Watase in 2020, front-line physicians estimated that one in seven unscheduled admissions could be avoided through an EDOU, to allow more time to address diagnostic uncertainty.41 A review in Health Services and Delivery Research identified Clinical Decision Units (CDUs) as having a similar effect.42

- Hospital at home programs: Certainly a Blue Ocean Strategy is the new field of inpatient-level care coordinated and delivered at home, referred to as the “hospital at home” movement.43-46 Patients are very satisfied and prefer to be treated in their homes whenever possible. This is different from hospice care in that the expectation is for the patient to receive treatment for treatable conditions. At the University of Texas San Antonio, patients that may be eligible are referred in real time to the hospital at home team who can screen and enroll patients into this program. It is one of the fastest growing programs in the Texas University Health System.47

- Disease-specific pathways: When considering outpatient management of conditions that have been historically managed as inpatient conditions, there is an ongoing debate as to whether or not a disease-specific pathway approach is better than a patient-population–specific approach. Examples of conditions that are amenable to clinical pathways around the country include those for congestive heart failure, cellulitis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, and chest pain.48,49 An example of a patient-population approach is the EDIFY work for frail adults.50

- ED-based discharge teams: The last initiative that is getting traction in this avoidable admissions arena is one where a physician, nurse, care coordinator, or any combination of the three is placed in the ED to identify patients that might have their care plan adapted to an outpatient-care process model.51-53

- Direct nursing home or rehab placement from the ED: Lastly, EDs are experimenting with placement agreements which allow the ED to place appropriate patients in nursing homes or rehab units without a hospitalization first. The Watase study found that this would reduce unavoidable admissions by 20 percent.42 A new study in a Spanish gerontology journal reported success with direct admission to a nursing home from the ED.54 This may be a new trend on the horizon.

When should you consider implementing the initiatives and tactics of a PATH program? If your hospital is constantly over capacity, with high numbers of hospital boarders every day, these initiatives are worth considering. Emergency physicians want to deliver high-quality, safe, and cost-effective care. That is not what we are delivering when admitted patients have long dwell times and there is no room to care for newly arriving patients. In fact, as a large body of literature shows, ED care suffers during boarding.

As emergency physicians we have been struggling with a nationwide boarding burden for over 20 years. It is not a problem of our making and we are not the keys to solving it. But we are the innovators and leaders in our hospitals. It is important that we be conversant in all sides of the boarding issue. We are right to demand that our respective hospital leaders address this problem using effective inpatient strategies for creating capacity. Now you have the playbook. In these extreme circumstances we can and should partner with hospital leaders to identify and manage avoidable admissions. It is time to turn our attention to the demand side of the throughput equation!

Dr. Welch practiced emergency medicine for 35 years. She was an ED quality director for Intermountain Healthcare. She has written articles and books on ED quality, safety, and efficiency. She is a consultant with Quality Matters Consulting, and her expertise is in ED operations, patient flow, and work flow.

Dr. Welch practiced emergency medicine for 35 years. She was an ED quality director for Intermountain Healthcare. She has written articles and books on ED quality, safety, and efficiency. She is a consultant with Quality Matters Consulting, and her expertise is in ED operations, patient flow, and work flow.

References

- Augustine J. A first look at emergency department data for 2022. ACEP Now website. https://www.acepnow.com/article/a-first-look-at-emergency-department-data-for-2022/2/. Published June 7, 2023. Accessed February 15, 2024.

- Leisman D, Huang V, Zhou Q, et al. Delayed second dose antibiotics for patients admitted from the emergency department with sepsis: Prevalence, risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med.2017;45(6): 956-65.

- Coil CJ, Flood JD, Belyeu BM, et al. The effect of emergency department boarding on order completion. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(6):730-36.

- Salehi L, Phalpher P, Valani R, et al. Emergency department boarding: a descriptive analysis and measurement of impact and outcomes. CJEM.2018;20(6):929-37.

- Krall SP, Guardiola J, Richman PB. Increased door to admission time is associated with prolonged throughput for ED patients discharged home. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(9): 1783-7.

- Wiler JL, Ozkaynak M, Bookman K, et al. Implementation of a front-end split-flow model to promote performance in an urban academic emergency department. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(6):271-80.

- Anderson JS, Burke RC, Augusto KD, et al. The effect of a rapid assessment zone on emergency department operations and throughput. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(2):236-45.

- Spencer S, Stephens K, Swanson-Biearman B, et al. Health care provider in triage to improve outcomes. J Emerg Nurs. 2019;45(5):561-6.

- Mahmood FT, AlGhamdi MM, AlQithmi MO, et al. The effect of having a physician in the triage area on the rate of patients leaving without being seen: A quality improvement initiative at King Fahad Specialist hospital. Saudi Med J. 2024;45(1):74-8.

- Russ S, Jones I, Aronsky D, et al. Placing physician orders at triage: the effect on length of stay. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):27-33.

- Rogg JG, White BA, Biddinger PD, et al DF. A long-term analysis of physician triage screening in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(4):374-80.

- Carney KP, Crespin A, Woerly G, et al. A front-end redesign with implementation of a novel “intake” system to improve patient flow in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2020;5(2):e263.

- Browder W. The Sacramento model improves multiple operations metrics in a high volume ED. Sentara Leigh Hospital poster presentation. ED Innovations 2018, Nashville.

- Welch, S. A behavioral health intake process model. ACEP Now website. https://www.acepnow.com/article/a-behavioral-health-intake-processmodel/. Published May 2, 2023. Accessed February 15, 2024.

- Pearlmutter MD, Dwyer KH, Burke LG, et al. Analysis of emergency department length of stay for mental health patients at ten Massachusetts emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(2):193-202.e16.

- Kraft CM, Morea P, Teresi B, et al. Characteristics, clinical care, and disposition barriers for mental health patients boarding in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:550-5.

- Schreyer KE, Martin R. The economics of an admissions holding unit. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(4):553-8.

- Alishahi Tabriz A, Birken SA, Shea CM, et al. What is full capacity protocol, and how is it implemented successfully? Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):73.

- Vermeulen M, Ray JG, Bell C, et al. Disequilibrium between admitted and discharged hospitalized patients affects emergency department length of stay. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(6):794-804.

- Khanna S, Sier D, Boyle J, et al. Discharge timeliness and its impact on hospital crowding and emergency department flow performance. Emerg Med Australasia. 2016;28:164-170.

- Mustafa F, Gilligan P, Obu D, et al. Delayed discharges and boarders: A 2 year study of the relationship between patients experiencing delayed discharges from an acute hospital and boarding of admitted patients in a crowded ED. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(9):636-640.

- Van Walraven C. The influence of hospitalist continuity on the likelihood of patient discharge in general medicine patients. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):692-4.

- Huang KT, Minahan J, Brita-Rossi P, et al. All together now: Impact of a regionalization and bedside rounding initiative on the efficiency and inclusiveness of clinical rounds. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):150-6.

- Mirabella AC, McAMis NE, Kiassat C, et al. Preferences to improve rounding efficiency among hospitalists: a survey analysis. J Community Hosp Internal Med Perspect. 2021;11(4):501-6.

- Sehgal NL, Green A, Vidyarthi AR, et al. Patient whiteboards as a communication tool in the hospital setting: a survey of practices and recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(4):239.

- Mehta RL, Baxendale Bryn, Roth K, et al. Assessing the impact of the introduction of an electronic hospital discharge system on the completeness and timeliness of discharge communication: a before and after study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:624

- Tan M, Hooper Evans K, Braddock CH, et al. Patient whiteboards to improve patient centered care in the hospital. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89(1056):604-9.

- Rojas-Garcia A, Turner S, Pizzo E, et al. Impact and experiences of delayed discharge: A mixed-studies systematic review. Health Expect. 2017;00:1-16.

- Landeiro F, Roberts K, Gray AM, et al. Delayed Hospital discharges of older patients: A systematic review on prevalence and costs. Gerontologist.2019;59(2):e86-e97.

- Patel H, Morduchowicz S, Mourand, M. Using a systematic framework of interventions to improve early discharges. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2017;43:189-96.

- Cressman AM, Purohit U, Shadowitz E, et al. Potentially avoidable admissions to general internal medicine at an academic teaching hospital: an observational study. CMAJ Open. 2023;11(1):E201-E207.

- Robinson J, Boyd M, O’Callaghan A, et al. The extent and cost of potentially avoidable admissions in hospital inpatients with palliative care needs: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5(3):266-72.

- Kilaru AS, Resnick D, Flynn D, et al. Practical alternative to hospitalization for emergency department patients (PATH): A feasibility study. Healthc (Amst).2021;9(3):100545.

- Woodhams V, de Lusignan S, Mughal S, et al. Triumph of hope over experience: learning from interventions to reduce avoidable hospital admissions identified through an Academic Health and Social Care Network. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:153.

- Soto GE, Huenefeldt EA, Hengst MN, et al. Implementation and impact analysis of a transitional care pathway for patients presenting to the emergency department with cardiac-related complaints. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):672.

- Zierler, Amy. Effect of early follow-up after hospital discharge on outcomes in patients with heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2017;17(8):1-37.

- Carmel A, Steel P, Tanouye R, et al. Rapid primary care follow-up from the ED to reduce avoidable hospital admissions. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(5):870-7.

- Gettel CJ, Serina PT, Uzamere I, et al. Emergency department-to-community care transition barriers: A qualitative study of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(11):3152-62.

- Seidenfeld J, Stechuchak KM, Coffman CJ, et al. Exploring differential response to an emergency department-based care transition intervention. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:640-5.

- Lillebo B, Dyrstad B, Grimsmo A. Avoidable emergency admissions? Emerg Med J. 2013;30(9):707-11.

- Watase T, Jablonowski K, Sabbatini A. Prospective analysis of alternative services and cost savings of avoidable admissions from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(3):624-8.

- Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, Stukel TA, et al. Evaluating the effect of clinical decision units on patient flow in seven Canadian emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(7):828-36.

- Gaillard G, Russinoff I. Hospital at home: A change in the course of care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2023;35(3):179-182.

- Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):77-85.

- Leong MQ, Lim CW, Lai YF. Comparison of hospital-at-home models: a systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e043285.

- Baugh CW, Dorner SC, Levine DM, et al. Acute home-based care for patients with cancer to avoid, substitute, and follow emergency department visits: a conceptual framework using Porter‘s five forces. Emerg Cancer Care. 2022;1(1):8.

- Banos E. The hospital at home program at UHS. Conference presentation, Innovations in ED Management 2023. April 2023, Phoenix, AZ.

- Bhatti Y, Stevenson A, Weerasuriya S, et al. Reducing avoidable chest pain admissions and implementing high-sensitivity troponin testing. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(4):e000629.

- Schechtman M, Kocher KE, Nypaver MM, et al. Michigan emergency department leader attitudes toward and experiences with clinical pathways to guide admission decisions: a mixed-methods study. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(4):384-93.

- Pinkney J, Rance S, Benger J, et al. How can frontline expertise and new models of care best contribute to safely reducing avoidable acute admissions? A mixed-methods study of four acute hospitals. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2016.

- Woodhams V, de Lusignan S, Mughal S, et al. Triumph of hope over experience: learning from interventions to reduce avoidable hospital admissions identified through an academic health and social care network. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:153.

- Katz EB, Carrier ER, Umscheid CA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of care coordination interventions in the emergency department: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):12-23.

- Chong E, Zhu B, Tan H, et al. Emergency department interventions for frailty (EDIFY): front-door geriatric care can reduce acute admissions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(4):923-8.e5.

- Cristofori G, González Becerra M, Sánchez Osorio LM, et al. Utilidad y seguridad de los ingresos directos a una unidad hospitalaria de agudos de un servicio de geriatría valorados por atención geriátrica en residencias [Utility and safety of direct admission to acute geriatric unit after Nursing Home Geriatric Team assessment]. [Spanish] Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2023;58(6):101388.

One Response to “Survival Tactics for Emergency Department Boarding”

March 10, 2024

Todd B Taylor, MD, FACEPThank you Shari. Your contribution to addressing this & other serious healthcare issues over the years has been laudable.

The failure of inpatient bed capacity to keep up with population is stark, albeit sameday outpatient surgery with new techniques have changed a 2-day hospital stay into a long afternoon in post-op. And, changes in healthcare funding policy has forced hospitals & others to dramatically change business practices.

In Arizona, in the late 1990’s to late 2000’s the Arizona ACEP Chapter had a huge impact on hospital crowding, to which you alluded.

But, now, here we are again & what appears to be worse & more wide-spread. So once again, the Arizona Chapter Board is taking action to draw attention to & impact this serious issue.

This time, we have chosen to employ data (not readily available in the past) to incentivize hospitals to take appropriate action & join with the EM community to lobby for policy changes. Anyone interested may contact me for a summary.

Thanks again for summarizing this timely topic.