Dr. Kevin Klauer: I’m very excited and interested to talk to you because of your background in innovation with technology as well as your formal training in cardiology and your recent thoughts on combining those two disciplines to try to make care delivery more efficient.

Dr. Eric Topol: I think what’s really exciting is that there is emerging technology that is truly transformative, that puts the consumer, the patient, in a very unique position of actually generating a lot of data and then having algorithms, cloud computing, even machine learning to help provide that data back to the individual. In many ways, it’s the decompressed diagnostic monitoring aspect of doctoring.

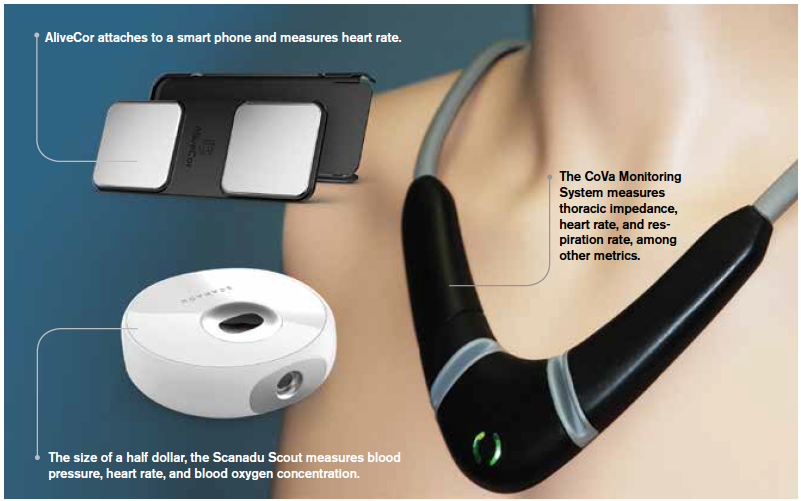

KK: I saw a recent interview you did for CBS on January 6th, and it was great, as you were able to bring some gadgets with you. One I think I’ve seen before is AliveCor, with the two-finger rhythm strip. One of the devices looked like a Star Trek necklace, [the CoVa Monitoring System]. I felt really bad for you because it looked like it wasn’t working right.

ET: The device was working really well, but the prop guy for CBS played with it when they took it from me, and by the time I got on live TV, it was all screwed up. I couldn’t get it back quickly. That necklace is a really good example because you can get cardiac output stroke volume with every heartbeat and thoracic fluid, so for somebody with heart failure—or let’s say if you’re an emergency room physician—instead of having to put a Swan-Ganz in, which you’re not likely to do in the emergency room, you could actually get these kind of hemodynamics quickly.

KK: This technology is fascinating, but have these devices stood up to scientific rigor and external validation?

ET: That testing is happening right now, but I’m familiar with data from hundreds of patients, many of them in intensive care units with heart failure, where they’ve had the data side by side with our conventional way of testing it. It looks promising, but we always need more validation before we go into wide-scale use. The other [technology] that is exciting is a watch that reads your blood pressure with every heartbeat. With 70 million Americans who have hypertension, the ability to get vital signs like blood pressure in the real world for each individual contextualized with their life is really a phenomenal step forward, and that looks promising with respect to accuracy.

KK: What about that other technology that you were demonstrating that was almost like a temporal artery blood pressure monitor?

ET: We’re testing that right now at Scripps. It’s called Scanadu Scout, and it’s about the size of a half dollar. You hold it up to your temple, and you get blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen concentration in the blood. You could carry it in your pocket or your purse, and if you need to get all of your vital signs intermittently, it takes about 10 seconds. Who would’ve ever thought that that would be possible?

KK: Do you think this technology is better in the hands of a physician guiding care with their patient?

ET: At the end of the day, the consumers should be able to make that call. What I’ve learned is that with most patients who are worried about their heart rhythm, this electrocardiogram technology gives them a reading that is normal, and it’s very reassuring. It saves a lot of emergency care visits and urgent care visits. It should be the choice of the patient, but obviously, they have the ability to consult with their doctor and ask them.

KK: Let’s say someone has chest pain, and they decide to use this device to decide whether they should go to the emergency department. Let’s make it even better—say they have palpitations or they feel a rapid heartbeat, but it’s paroxysmal. They look at the rhythm strip, see nothing wrong, and think, “I don’t have to go to the emergency department.” Maybe they didn’t define the abnormal rhythm they had. Or let’s say it wasn’t the rhythm that was the primary problem. They have a pulmonary embolism, which is why they feel that sense of tachycardia. The strip read as normal, but their resting heart rate is 60 and their current heart rate is 90. From a relative standpoint, they’re tachycardic, but they just self-triaged themselves out of an emergency department. That worries me a little bit.

ET: Misdiagnosis is a big deal, but Kevin, I think you’re well aware we’ve got a little problem with that right now anyway. Twelve million Americans or more each year are getting a serious misdiagnosis. We’re working toward this ability to integrate multiscaled, multilayered information so that it wouldn’t just be one metric. You’d see the oxygen concentration, the SpO2, drop with the tachycardia, and you’d say, “I suspect a pulmonary embolism.” The point is that things are getting datafied, more objective, and there are these machines that can actually do a good job of processing the data and learning. I’m predicting over time that this could work pretty well. It isn’t the same as a doctor, but it’s processing a lot of objective data in a meaningful way. Someday it could be a kind of medical Turing test [test of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human] where you have a computer doing a pretty darn good job in terms of accuracy. Diagnosis is different from treatment; that’s where the doctor has to come in, and the doctor would provide oversight that the diagnosis was correct.

KK: Back to that interview, it sounds like, in talking to you now, that your perspective is that as this evolves, there may be some more intricate ways to risk stratify and to help people make the decision as opposed to the example that was given, which was to use the rhythm strip, and you don’t have to end up going to the emergency department—“go through all the rigmarole,” you said in the CBS interview—if the rhythm strip is interpreted as normal. Is that what your perspective is, that would be enough, or do you think this just builds into a piece of a bigger puzzle that can help patients decide whether they have to go to the emergency department or not?

ET: Right, the piece of a bigger puzzle. We’re still in the relatively early stages, but the ability to integrate big data per each individual is where we’re headed. It’s exciting, but obviously, it’s a very big challenge for the medical community since it represents such a radical change.

KK: There’s the pervasive thought in America that the emergency department is overutilized, but we find that we’re the only type of facility that’s open 24-7 for any type of acute or unscheduled care. If you’re not sure what you have, we actually prefer that you would come to us.

ET: I agree with you about that, Kevin. The emergency room is not going away, unlike the hospital room, the actual room, which might not survive over the next decade. The emergency room is a really invaluable place because all of the technology we’re talking about is not for serious matters. For anything that’s significant, emergency rooms are here to stay, and they’re going to be a center for acute illness forever as far as I can see.

KK: How involved are you in the development and ownership of these technologies?

ET: None of them are our devices. [Scripps] just happens to be a place that validates them if you’re in clinical trials, so we get to see a lot of stuff and pick the ones that we want to do prospective rigorous studies on. It isn’t our stuff; we just have the ability to take innovative ideas largely from engineers and get them into the medical testing mode so that some of them will make it to routine incorporation and practice.

KK: With your involvement with validation and studies and your profession as a cardiologist, are there any conflicts of interest that you feel are present? Do you find it difficult to avoid?

ET: I do think it’s difficult to avoid. You have to separate out whether you’re going to work with a company and financially benefit from it or going to do basically independent validation.

KK: Our whole specialty is thinking about ways we can really make acute care delivery more efficient, and certainly better, for our patients. This could be a way for us to assess our patients after they leave the emergency department if they don’t have access to primary care. Maybe the emergency department can follow them for the next 72 hours if they have one of these devices [eg, congestive heart failure with the personal cardiac output monitoring device].

ET: I think that will bolster the confidence of emergency room doctors if people are getting really good monitoring when they leave the emergency department.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Is Technology Putting Health in the Hands of Patients or Taking It Out of the Hands of Physicians?: An Interview with Dr. Eric Topol”