In the emergency department (ED), physicians face the challenge of making rapid decisions that can significantly impact patient outcomes. These decisions often require a balance between clinical acumen and an open-minded approach, particularly in cases where symptoms could point to both mental health crises and physical health issues. A recent encounter highlights the critical importance of avoiding diagnostic anchoring, especially in patients of color, those who present with mental health crises, and the intersection that lies between them.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 10 – October 2024The patient, a 25-year-old male of color, arrived at the ED with persistent tachycardia, his heart rate consistently in the 120s. Accompanying this symptom was a significant “heavyweighted” chest discomfort that he had been experiencing for months. He had a prescription for a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for panic disorder and anxiety. He had a significant medical history of mental health crises, and this seemed to be his typical presentation pattern. Given his history, it could have been easy to attribute his current presentation to his known mental health conditions. However, the persistence of tachycardia despite fluid resuscitation and dosing with lorazepam to help with his panic disorder raised concerns that warranted further investigation.

Collaborating with one of my ultrasound faculty, we conducted a bedside echocardiogram to explore potential cardiac anomalies. This examination revealed focal septal hypertrophy and raised concerns for systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve, findings that pointed to a potential physical underpinning for the patient’s symptoms. The patient had an assortment of previous doctor’s visits attempting to identify the cause of his panic episodes. Furthermore, this patient had been having episodes of palpitations that had been worsening since he was a teen, and there was, unfortunately, never an investigation regarding these persistent episodes.

HOCM in the ED

HOCM is not an everyday diagnosis in the ER. However, this should not deter us from including it in our differential, especially among younger patients. Up to 30 percent of people in this population will not have any family history at all before HOCM is identified.1 The diminished left ventricular function in HOCM is often associated with the thickening of the interventricular septum, which is also associated with increased left ventricular wall thickness equal to 15 mm or more. Furthermore, this genetic cardiac disease is autosomal dominant, presenting 1 in 500 in our general population.2 This is particularly problematic as we know that many of our HOCM patients, despite being asymptomatic, have nearly a 25 percent chance of sudden cardiac death.3 This data further emphasizes how life-changing a diagnosis can be if caught early.

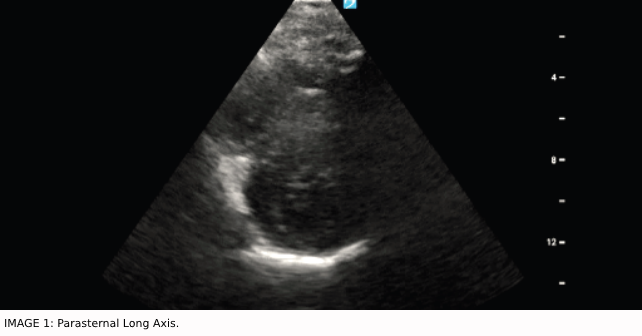

Our workup started with an ultrasound and EKG. There is a decreased diameter of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) in the setting of obstructive cardiomyopathy pathology and thickened septum.4 This is seen in the parasternal long axis image (Image 1). Furthermore, we can see systolic anterior motion or SAM in patients with HOCM.5 SAM occurs when the mitral valve is displaced toward the LVOT and causes obstruction causing further dysfunction and limited flow for these patients. EKGs will have abnormalities in about 90 percent, but they are typically nonspecific findings. In addition, we observed in his EKG high-voltage, LVH, left atrial enlargement, tall R-wave in V1, and Q waves that were like needles.6

After a diagnosis is made, treatment can start with beta blockers for angina or dyspnea in adults with HCOM, no matter the type of obstruction. Beta-blockers are a class I recommendation per the American College of Cardiology.7 However, be cautious in the case of sinus bradycardia. Verapamil is also a reasonable option as it is also a class I recommendation. Class IIa recommendations include disopyramide with beta-blockers or verapamil if not responsive to either alone. Oral diuretics are another option. Avoid nifedipine, other dihydropyridine CCB, digoxin, disopyramide alone, and positive inotropic vasopressors, as these can precipitate harm.7 Once the diagnosis is identified, it is imperative to get cardiology consultation and arrange for a further workup, including a formal echocardiogram.

The Value of the Story

This case exemplifies the critical need for health care professionals to approach each patient encounter without bias, especially when dealing with populations of color who have recently suffered disproportionately from mental health disorders.8 Diagnostic anchoring when evaluating patients presenting for seemingly mental health issues can prevent the recognition of pertinent physical health issues, leading to misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment. A study done by emergency medicine physicians in Japan identified that a group of experienced physicians they surveyed had up to 22 percent of diagnostic errors due to overconfidence, confirmation, availability, or anchoring biases.9 Even for the most experienced, maintaining an open mind to other possibilities can provide our patients with the best care.

Influencing Emergency Medicine Provision

The story demonstrates the necessity of treating each workup as a new investigation, irrespective of the patient’s prior medical history. It serves as a reminder that symptoms can have multiple etiologies, and a thorough examination is essential to uncover the underlying cause. When a patient presents with “anxiety,” is the symptom masquerading as something more sinister? Are we missing a critical differential or not thinking of an organic presentation? This approach is particularly relevant in emergency medicine, where the pressure to make quick decisions can inadvertently lead to reliance on mental shortcuts, or heuristics, that might not serve the patient’s best interest. This mindset shift is crucial for improving outcomes and fostering a more inclusive and equitable health care system.

This case from my early residency experience poignantly reminds me of the complexities inherent in medical diagnosis, particularly at the intersection of mental health and physical illness. By adopting a holistic and unbiased approach to patient care, emergency physicians and other diagnosticians can better serve their patients, ensuring that no stone is left unturned in the pursuit of accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Dr. Harrell is a PGY-1 emergency physician at Houston Health.

Dr. Harrell is a PGY-1 emergency physician at Houston Health.

Dr. Bower is an emergency physician at Houston Health.

Dr. Bower is an emergency physician at Houston Health.

References

- Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Executive summary: A report of the American College of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124(24):2761-2796.

- Pantazis A, Vischer AS, Perez-Tome MC, Castelletti S. Diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Echo Res Pract. 2015;2(1):R45.

- Maron BJ, Casey SA, Poliac LC, Gohman TE, Almquist AK, Aeppli DM. Clinical Course of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in a Regional United States Cohort. JAMA. 1999;281(7):650-655.

- Maron MS, Olivotto I, Betocchi S, et al. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia. 2003;22(3):465-466.

- Ibrahim M, Rao C, Ashrafian H, Chaudhry U, Darzi A, Athanasiou T. Modern management of systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41(6):1260-1270.

- Burns E, Buttner R. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) • LITFL • ECG Library Diagnosis. Published 2022. Accessed April 17, 2024.

- Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(25):212-260.

- Thomeer MB, Moody MD, Yahirun J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health and Mental Health Care During The COVID-19 Pandemic. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(2):961.

- Kunitomo K, Harada T, Watari T. Cognitive biases encountered by physicians in the emergency room. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(1):1-8.

Correction: Dr. Harrell’s photo was incorrect and has been replaced. ACEP Now regrets the error.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “The Intersections of Physical and Mental Health Disorders”