Violence in the emergency department is not a new phenomenon. Our specialty has been fighting for workplace safety for more than 25 years. ACEP issued a policy statement in 1993 titled “Protection from Physical Violence in the Emergency Department.”1 The 2016 policy revision, with the same title sans the word “physical,” states that “optimal patient care can only be achieved when we are all safe and protected from violence.”2 How true. The policy calls for increased awareness and increased safety measures, including adequate security personnel, sufficient training of personnel, physical barriers, surveillance equipment, and security components.

Explore This Issue

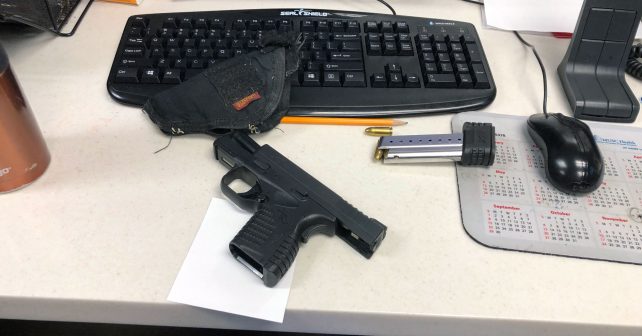

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 11 – November 2020One of the safety measures is the use of metal detectors, which include hand-held and walk-through (WT) metal detectors. It is not uncommon for ED personnel to find weapons in patient care areas that might otherwise have been confiscated prior to entry (see Figure 1). In one 26-month study, after introducing WT metal detectors in the ED entrance at one hospital, nearly 6,000 weapons, including 268 firearms and 4,842 knives, were retrieved.3 Even with these data showing that metal detector use results in weapon retrieval, widely varying policies still exist regarding their use as screening tools to enhance safety.

There must be reasons why implementing metal detectors has barriers or else they would probably already be universal in emergency departments. Concerns for efficacy, cost with regard to staffing and equipment, and perception are a few of those barriers. The study by Malka et al addresses efficacy.3 Cost would vary with types of equipment purchased and staffing model and would be the topic for another discussion. So let’s address perceptions as a barrier to implementation of metal detectors in emergency departments.

There must be reasons why implementing metal detectors has barriers or else they would probably already be universal in emergency departments. Concerns for efficacy, cost with regard to staffing and equipment, and perception are a few of those barriers. The study by Malka et al addresses efficacy.3 Cost would vary with types of equipment purchased and staffing model and would be the topic for another discussion. So let’s address perceptions as a barrier to implementation of metal detectors in emergency departments.

Our institutional policy currently mandates activation of WT metal detectors only when EMS arrival of gunshot wound victims is identified. In meetings addressing increasing ED violence, administrators argued that the presence of a metal detectors at the entrance to the emergency department might convey to the public the impression of a potentially dangerous environment. In other words, utilizing our metal detectors 365-24-7 would create a bad public image. This would result in fewer visits and referrals and loss of revenue for our hospital. That got our analytical wheels turning. If we feel safer when metal detectors are used at a public place where concern exists for violence, such as the airport, why wouldn’t patients, visitors, and staff feel safer in the health care arena with the same precautions? Was this negative perception concern real?

Two studies looked into metal detectors perception back in 1997. In the first, 75 percent of patients already felt safe and 68 percent were satisfied with the security. However, 11 percent felt a fear of being physically harmed in the emergency department, and two-thirds reported they would feel better with a metal detector in use. The authors concluded that the concerns over the potential for negative imaging around metal detectors was not warranted.4 In the second study, 80 percent of patrons and 85 percent of employees liked the metal detector, with 89 percent of patrons and 73 percent of employees feeling safer with its use. Thirty-nine percent were more likely to return because of it, while just 1 percent said they were less likely to return as a result.5

In 2017, Dr. Russell Allinder, Dr. Steven Saef, and I set out to determine the current perception of metal detector and security officer usage in our emergency department. We realized that public perception may have changed over the course of those two decades and that negative perception might be a valid concern. The survey included more than 300 ED patients, visitors, and staff at our southeastern academic Level 1 trauma center.

Among other results, we found that surveyed participants would not perceive the emergency department as a more dangerous place if WT metal detectors were routinely utilized. In fact, a majority of participants (75 percent) stated they would feel safer if a WT metal detector was in use, with African Americans reporting greater perceived safety benefit than Caucasians in a bivariate analysis (P<0.001). Security officer visibility increased safety perception for 72 percent of participants. WT metal detector usage at the entrance would not adversely affect willingness to return to the emergency department for 99 percent of respondents.

Bottom line: The notion that the public perceives the emergency department as less safe and therefore avoid future ED care when metal detectors are used is simply not true, as shown in our study. This argument should not be used as an argument against their use. Emergency medicine workers are at high risk for workplace violence. We deserve to be safe while we serve populations that need us to be their safety net. Though one piece to a very large puzzle, having an active metal detector may prevent weapons in the patient care area and deter violence in the emergency department, allowing us to safely do our job.

References

- Protection from physical violence in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(10):1651.

- Protection from violence in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(3):403-404.

- Malka ST, Chisholm R, Doehring M, et al. Weapons retrieved after the implementation of emergency department metal detection. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(3):355-358.

- McNamara R, Yu DK, Kelly JJ. Public perception of safety and metal detectors in an urban emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15(1):40-42.

- Meyer T, Wrenn K, Wright SW, et al. Attitudes toward the use of a metal detector in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29(5):621-624.

Dr. Krywko is professor of emergency medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Dr. Krywko is professor of emergency medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Time to Put Negative Perceptions of Metal Detectors to Rest”