At numerous recent conferences, a panoply of creative and insightful clinicians have been redefining cutting-edge emergency airway management. Emergency medicine, critical care, and social media giant Scott Weingart, MD, FCCM, has long warned us of the dangers of intubation before resuscitation. The incredible Social Media and Critical Care (SMACC) conference triumvirate of Roger Harris, MD, Chris Nickson, MBChB, and Oliver Flower, MBBS, BMedSci, have also emphasized intubation is but one part of resuscitation in the critically ill. Innovative educator Reuben Strayer, MD, has been promoting alternatives to rapid sequence intubation (RSI), specifically the use of ketamine assisted intubation in patients who have no margin for safe apnea.

At SMACC, held in Chicago June 23–26, Dr. Weingart talked about the fact that RSI does not need to be first line in the critically ill patient and often shouldn’t be performed. Correcting hypoxia and performing resuscitation should precede intubation. He coined the term “DSI” for delayed sequence intubation, using ketamine to allow for critical interventions prior to intubation (eg, noninvasive ventilation, nasogastric decompression, etc.).1 In his words, “avoid using the laryngoscope as murder weapon.” Dr. Harris and Dr. Nickson stated repetitively at my recent Yellowstone Airway and Critical Care Course, “resuscitate, then intubate” the critically ill.

This got me thinking of our term “RSI,” which in emergency medicine refers to “rapid sequence intubation.” Ron Walls, MD, FACEP, and others adapted the term from “rapid sequence induction,” which was well established by anesthesia long before emergency medicine existed and referred to the sequence of giving an induction agent and then immediately giving a muscle relaxant. Kudos to Dr. Walls for getting emergency medicine to widely adopt muscle relaxants. Conventional intubation in the operating room environment historically involved administering an induction agent followed by verification of the ability to mask ventilate before the administration a muscle relaxant. Curiously, this sequence was not adopted in other areas of the world. Within the United Kingdom, there has long been a practice of giving both drugs at the same time and a belief that proving ventilation before a relaxant is not safety enhancing.2 Numerous recent articles and editorials have argued, in fact, that trying to prove mask ventilation first is pointless. Muscle relaxants have been shown to enhance the ability to mask ventilate, and they also clearly optimize intubating conditions, but perhaps most significantly nowadays, they allow placement of a supraglottic airway (eg, laryngeal mask airway, King LT, etc.) without risk of gagging and vomiting.3

Slow Down

Returning to our use of the term “rapid,” I have recently realized how much rushing and emphasizing speed has been deleterious to our crisis performance in airway management. The most common mistake in laryngoscopy, direct and video, is overrunning the epiglottis. Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast. I now advocate holding laryngoscopes (direct or video device) with the lightest possible two fingers and thumb grip just to slow down device insertion, gently distract tongue, and find the epiglottis on insertion by rolling midline down the tongue, dabbing mucosa with the Yankauer, then doing tongue control as needed. “Rapid” is bad neurolinguistically in both laryngoscopy or tube delivery, and we should be especially careful to avoid “rapid” following RSI drug administration and inserting a laryngoscope too early. I now close the communication loop with nurses explicitly when giving RSI meds. I have the nurse give the induction agent and muscle relaxant and then have the same person call out “60 seconds” to avoid my starting laryngoscopy too rapidly after administering the drugs, which could cause the patient to gag and vomit.

Watch for Shock

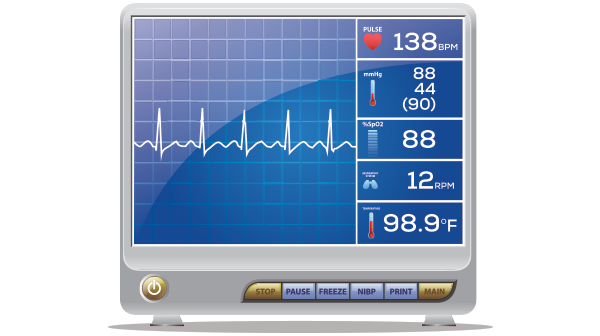

Optimizing oxygenation prior to intubation is, in hindsight, a no-brainer. It’s rare that plastic needs to go in the trachea now; usually, it’s oxygen that needs to get into the lungs and bloodstream. The other group of patients who require what I now realize is “resuscitation sequenced intubation” are those in shock. One way to recognize these cases is through the routine assessment of the Shock Index. Shock Index refers to the ratio of the heart rate over the systolic blood pressure. Normally, this ratio is between 0.5 and 0.8. When heart rate and systolic blood pressure are equal, the ratio is 1.0. Above a Shock Index of 1.0, the combination of using positive pressure ventilation, taking away adrenergic tone, and creating muscle relaxation can cause precipitous hypotension and cardiac arrest. For this reason, some have advocated push-dose vasopressors for all RSI cases. Another approach is to time the intubation after the resuscitation has been undertaken (ie, get the fluids in and start the vasopressor drip [norepinephrine usually], correcting hypotension before intubation is attempted).

“Rapid?” The most common mistake in laryngoscopy, direct and video, is overrunning the epiglottis. Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.

The Shock Index has been studied as it relates to intubation in the emergency department and found to be the most useful predictor of peri-intubation cardiac arrest. Heffner and colleagues noted the incidence of peri-intubation cardiac arrest to be more than 4 percent.4 It was associated with higher in-house death (odds ratio of 14.8) and was most commonly associated with pre-intubation hypotension (12 percent of patients who were initially hypotensive arrested versus only 3 percent of other patients).

In some very ill patients, it may be necessary to avoid intubation if at all possible. I recently had a patient in complete heart block with hypotension from an anterior-inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. With pacing and vasopressors, she arrived to the cath lab in time, and intubation was completely avoided. In hindsight, I think she would not have tolerated the hemodynamic consequences of intubation.

As the bar of practice in emergency airways continues to be raised, as we are more and more becoming critical care doctors (by default, the way our EDs are running), it’s important to expand our perspective. Placing plastic in the trachea is but one part of our critical care responsibilities. Along with optimizing oxygenation prior to intubation (nasal oxygenation, DSI, ketamine assisted intubation, etc.), assessing Shock Index is helpful in identifying patients who need resuscitation sequence intubation, not rapid intubation.

References

- Weingart SD, Trueger NS, Wong N, et al. Delayed sequence intubation: a prospective observational study. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:349-355.

- Calder I, Yentis SM. Could ‘safe practice’ be compromising safe practice? Should anaesthetists have to demonstrate that face mask ventilation is possible before giving a neuromuscular blocker? Anaesthesia. 2008;63:113-115.

- Warters RD, Szabo TA, Spinale FG, et al. The effect of neuromuscular blockade on mask ventilation. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:163-167.

- Heffner AC, Swords DS, Neale MN, et al. Incidence and factors associated with cardiac arrest complicating emergency airway management. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1500-1504.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Timing Resuscitation Sequence Intubation for Critically Ill Patients”

August 30, 2015

Tim Leeuwenburg…and don’t forget the many other modifications to the traditional RSI approach as described by Stept and Safar many moons ago

Times change – and we need to understand how modifications to RSI are necessary in the critically unwell – and to back this up with consensus statements to avoid post hoc criticism or medicolegal opinion from ‘experts’ who are usually confined to the Operating Theatre

Have a look at this for starters. Getting an international consensus guideline on airway management and DSI-RSI in critically unwell would be useful…

http://www.criticalcarehorizons.com/airway-management-of-the-critically-ill-patient/