Case 2

Case 3

Photos: Arun Sayal, MD, CCFP(EM)

Written from the perspective of an emergency physician who also runs a weekly minor fracture clinic, this column is intended to highlight a few key ED teaching points for commonly missed and commonly mismanaged ED orthopedic cases.

Case 1

A 22-year-old female falls, injures her ankle, and is non-weight-bearing. Lateral ankle pain is noted. The Ottawa

ankle rules (OAR) indicated X-rays, and the emergency department images are above (Case 1, Figure 1).

Case 2

A 45-year-old male slips on a sidewalk. He has mild lateral pain, his medial malleolus is non-tender, and he is non-weight-bearing. The OAR indicated X-rays, and the emergency department images are above (Case 2, Figure 1).

Case 3

A 13-year-old female slips playing soccer. She has mild lateral pain but is non-weight-bearing. The OAR indicated X-rays, and the emergency department images are above (Case 3, Figure 1).

What Happened in the Emergency Department?

- Case 1: The 22-year-old female was diagnosed with a severe lateral ankle sprain. She was treated with a walking boot, crutches, and follow-up in the minor fracture clinic.

- Case 2: The 45-year-old male was diagnosed with a soft tissue injury (STI) of the ankle. He was treated with an air-stirrup, crutches, and follow-up in the minor fracture clinic.

- Case 3: The 13-year-old female was diagnosed with a Salter-Harris I fracture in the distal fibula. She was treated with an air-stirrup, crutches, and follow-up in the minor fracture clinic

What happened in the end? Well, all three cases were surgical (see Case 1, Figure 2; Case 2, Figure 2; and Case 3, Figure 2).

The details of each case are below, but in the bigger picture, it’s worth discussing reasons the OAR can be “bad to the bone.” The OAR ask us to palpate the posterior aspects of the medial and lateral malleoli. However, there also are important structures to examine in the front and back of the ankle. This article will focus on commonly missed injuries at the front of the ankle joint.

Ankle injuries are frequently seen in emergency departments. The majority of ankle injuries are sprains; fewer than 15 percent of ED X-rays reveal fractures. To reduce the number of X-rays ordered, the OAR were proposed more than 25 years ago. They have subsequently been validated and implemented with reasonable success and acceptance.1–7

The OAR are a very good clinical decision instrument when used properly. They are designed to simply help decide which emergency department patients with ankle injuries require an X-ray. They should only be used after a proper assessment has been completed.

Over time, the OAR seem to have transformed from an emergency department X-ray utilization tool to an emergency department ankle examination tool. This is not what the OAR were intended for. While this observation is anecdotal from my experiences teaching in the emergency department, during courses, and following up with ED patients with acute ankle injuries in the minor fracture clinic, you may find this pattern sounds familiar.

For some practitioners, the ED ankle assessment has been condensed to the application of the OAR. If a patient twisted an ankle, one asks about weight-bearing, then palpates the four sites of tenderness for the OAR (the posterior 6 cm of the lateral malleolus, the posterior 6 cm of the medial malleolus, the navicular, and the base of the 5th metatarsal). After checking the distal neurovascular status, the ankle exam is done! When indicated, the X-ray is ordered and interpreted, and if negative, the patient is diagnosed with STI of the ankle. Next patient! Well, not so fast.

While the OAR have some value, they are only a small part of the emergency department ankle assessment. Beyond the OAR, there are other vital aspects of the ankle/foot assessment. A proper emergency department ankle assessment requires understanding:

- The mechanism of injury, the forces involved, and the events after injury

- Previous injuries to the ankle (and to the opposite, comparison ankle)

- Relevant past medical history (neuropathy, long-term steroids, etc.)

- An efficient and complete exam of the lower leg, ankle, and foot (Look, Feel, Move—inspect, palpate, range of motion)

- The specific differential diagnosis based on the patient’s injury and evaluation

With all of this, one can then interpret the X-rays in the context of the patient’s differential diagnosis. Radiologists are often asked to interpret X-rays without clinical information. As emergency physicians, we obviously have access to the clinical side. Interpreting X-rays without that clinical information is unnecessarily stacking the deck against us.

These three cases highlight the importance of the history and examination of the anterior aspect of the ankle. All three were seen by excellent emergency physicians. Despite that, all three were subtle misdiagnoses. All three were operative cases. All three had worrisome histories and were tender over the anterior aspect of the ankle, but these findings were not discovered in the emergency department. Two of the three had abnormal X-rays. In retrospect, some may call them fairly obvious radiologic abnormalities. However, the concerning mechanisms were not identified by history, and focal tenderness was not identified on exam. As a result, these uncommon injuries were not part of the differential and were not sought on X-ray interpretation. Just as a pneumothorax can be hard to see if you don’t look for it, these injuries can easily be overlooked if they are not considered. The clues to consider them are often found in the patient’s history and physical exam.

Case 1, Figure 2: 22-year-old female

Case 2, Figure 2: 45-year-old male

Case 3, Figure 2: 13-year-old female

Case 1

The emergency physician noted the patient fell and injured her ankle. The ankle was swollen and tender laterally, but there was no emergency department assessment of her anterior ankle. Diagnosis: severe lateral ankle sprain. She was given a walking boot and crutches, with follow-up in a week.

A few extra details: In fact, she jumped from a wall about six to seven feet high, landed on her feet, then fell over. Unable to walk, she presented to the emergency department the same evening. No anterior joint/talar pain was documented in the emergency department note on the initial visit. However, she was noted to be quite tender there when she returned the next day (after she was called back to the emergency department for an X-ray discrepancy). The original emergency department X-rays (cropped) are in Case 1, Figure 3.

Case 1, Figure 4 includes arrows to show some of the fracture lines visible throughout the talus.

The X-ray study was read as “no fracture” by the emergency physician. The radiologist identified the fractured talus. The patient returned to the emergency department the next day, and a CT scan in Case 1, Figure 5 showed the shattered talus.

The patient was admitted for surgical management, as shown in Case 1, Figure 2.

Case 1 highlights the importance of the history (eg, mechanism, force, and events after) and physical examination (eg, examining the anterior aspect of the ankle). Once the patient’s story is understood, the physician will then look at the X-rays with more focus and should also search for known associated injuries (eg, calcaneus, other foot, knees, hips, and the thoracolumbar spine).

Case 1, Figure 3

Case 1, Figure 4

Case 1, Figure 5

Case 2

The emergency department report showed the patient had mild tenderness laterally and no tenderness over the medial malleolus. He was diagnosed with a STI of the ankle, placed in an air-stirrup, given crutches, and provided with follow-up in the clinic in a week.

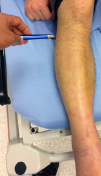

He came back on day 10. He was quite specific about the mechanism. He caught the instep of his right foot, and as his left foot went forward, his injured right foot clearly turned out. The mechanism was external rotation, a red flag mechanism. He was unable to bear weight up. At the patient’s follow-up exam, the emergency physician stated, “The patient had very mild tenderness laterally, and he was non-tender over the medial malleolus.” However, as images Case 2, Figure 3A–C show, he also had pain at three other points (points the OAR do not ask us to examine).

Case 2, Figure 3A: The deltoid ligament, below the medial malleolus.

Case 2, Figure 3B: Above the ankle joint, over the syndesmosis.

Case 2, Figure 3C: The proximal fibula.

Case 2, Figure 3A

Case 2, Figure 3B

Case 2, Figure 3C

In the clinic on day 10, X-rays were taken of the tibia and fibula (Case 2, Figures 4A and 4B). The proximal fibula shows the oblique fracture of the fibula. The fracture is only seen on the lateral view (Case 2, Figure 4B), a reminder of the orthopedic mantra, “One view is one view too few.” He had the classic Maisonneuve fracture, an external rotation mechanism resulting in injuries to the medial ankle (deltoid ligament or medial malleolus), syndesmosis, and interosseous membrane exiting out the proximal third of the fibula with an oblique fracture.

The patient was referred to an orthopedic surgeon and had surgery the following day, as shown in Case 2, Figure 2.

The OAR ask us to examine the posterior 6 cm of the medial and lateral malleoli, which was done. However, that is not a complete emergency department ankle exam. One needs to palpate many structures to localize the pain and discover the pathology. In this case, the ankle exam also revealed pain over both the deltoid ligament and the syndesmosis. Neither of these are part of the OAR. Either one can be a red flag on physical, and the combination certainly is concerning for a higher fibular fracture, which on palpation can be quite subtle. So in cases of twisting ankle injuries with significant medial ankle pain and little or no lateral ankle pain, it is best to X-ray the ankle and add the tibia/fibula views as a separate X-ray study.

This case again highlights that the OAR are not a complete emergency department ankle exam; they are simply a tool to use after a proper ankle assessment to decide if an X-ray is indicated.

Case 2, Figure 4A

Case 2, Figure 4B

It can be a bit daunting to see the “normal” X-rays and then the intraoperative films. This case was a missed Maisonneuve fracture, a classic fracture that will often show up on board certification examinations. More important than nailing the exam question, we should make sure we know how to recognize it the next time we see an emergency department patient with an ankle injury. This was a very subtle case without medial malleolus fracture (he had the deltoid ligament equivalent) and without shift of the ankle mortise. If we mistakenly put all of our focus on the X-ray, we are more likely to miss uncommon injuries. Again, the importance of history, appreciating that external rotation is a red flag, and physical tenderness over the deltoid ligament and the syndesmosis cannot be overemphasized. Then interpret the X-ray in the proper clinical context.

Case 3

Case 3, Figure 3

The patient was diagnosed with a Salter-Harris I fracture, placed in an air-stirrup, given crutches, and followed up in the minor fracture clinic on day eight. She had not been walking on it due to the pain.

At follow-up, a little more detail on the mechanism of injury was obtained. She stated she was playing soccer on a muddy field and was wearing cleats. As she turned her body in to get away from another player, her foot remained stuck in the mud. In terms of mechanism, she was quite clear: Her body turned in with her foot stuck. This is external rotation of her ankle. Of note, the emergency physician had found her mildly sore at the distal fibular area and made the diagnosis of a Salter-Harris I fracture. Emergency department examination of the anterior joint line was not documented. When she came to the clinic, her pain was localized to the anterior joint line, as pictured in Case 3, Figure 3. Note the impressive swelling (better recognized when compared to the opposite side).

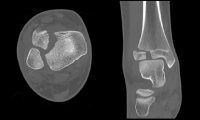

Case 3, Figure 4

Case 3, Figure 5

She was tender over the antero-lateral aspect of the distal tibia. She was non-tender over the lateral side along the fibula.

In reviewing the X-rays (Case 3, Figure 4, cropped) and now knowing where her pain localizes, it may be easier to detect the abnormality: a Salter-Harris III fracture of the distal tibial epiphysis, a Tillaux fracture.

Case 3, Figure 6

On the anterior-posterior and mortise views, a displaced intra-articular fracture is seen (Case 3, Figure 5, arrows). On the lateral view, it is subtle, but the fragment is mildly anteriorly displaced (Case 3, Figure 5, arrow).

This is a displaced intra-articular fracture. A CT scan confirmed the position. The patient underwent surgery the following day (see CT in Case 3, Figure 6, and intraoperative picture in Case 3, Figure 2).

A Tillaux fracture occurs in girls about 11–14 years old and boys about 12–15 years old because the distal tibial growth plate starts to fuse around these ages. It fuses from the medial half across to the lateral side. With external rotation, the syndesmosis (anterior distal tibiofibular ligament) is stressed, and the force separates the open (lateral) part of growth plate. When the force hits the closed part of the growth plate, the force exits down into the joint.8 The result is a Salter-Harris III fracture. This is the Tillaux fracture. Of note, a related injury exists, a Salter-Harris IV fracture. This has the same mechanism and involves the same age groups, but a triplane fracture can be seen on the lateral view to extend posteriorly up the distal tibial metaphysis.

Summary

These three injuries are uncommon but commonly missed. They serve to highlight the importance of mechanism and anterior joint line tenderness of the ankle. The clinical clues to these uncommon diagnoses are often present, but they can easily escape detection.

The cornerstones of the assessment are the mechanism plus the physical exam. A host of uncommon ankle injuries should be considered. The above three cases plus syndesmosis injury, Achilles tendon rupture, calcaneal fracture, and lateral process of the talus fracture are all diagnoses worthy of consideration. The list can be confidently narrowed by focusing on the mechanism of the injury (amount and direction of force) and the physical examination. When tenderness is found along the anterior joint line, consideration should be given to structures such as the syndesmosis, distal tibia, and talus. We can then interpret the X-rays within the proper clinical context and give proper attention to the areas of clinical concern.

Dr. Sayal is a staff physician in the emergency department and fracture clinic at North York General Hospital in Toronto, Ontario; creator and director of CASTED ‚Hands-On‘ Orthopedic Courses; and associate professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto.

References

- Stiell IG, Wells G, Laupacis A, et al. Multicentre trial to introduce the Ottawa ankle rules for use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Multicentre Ankle Rule Study Group. BMJ. 1995;311(7005):594-597.

- Auleley GR, Ravaud P, Giraudeau B, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa ankle rules in France. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;277(24):1935-1939.

- Yuen MC, Sim SW, Lam HS, et al. Validation of the Ottawa ankle rules in a Hong Kong ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(5):429-432.

- Knudsen R, Vijdea R, Damborg F. Validation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules in a Danish emergency department. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57(5):A4142.

- Can U, Ruckert R, Held U, et al. Safety and efficiency of the Ottawa ankle rule in a Swiss population with ankle sprains. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138(19-20):292-296.

- Bessen T, Clark R, Shakib S, et al. A multifaceted strategy for implementation of the Ottawa ankle rules in two emergency departments. BMJ. 2009;339:b3056.

- Leddy JJ, Kesari A, Smolinski RJ. Implementation of the Ottawa ankle rule in a university sports medicine center. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(1):57-62.

- Wheeless CR. Tillaux fracture In: Wheeless CR, Nunley JA II, Urbaniak JR, eds. Wheeless’ Textbook of Orthopaedics. Data Trace Internet Publishing, LLC; 2015. Accessed Jan. 18, 2018.

2 Responses to “Tips for Catching Commonly Missed Ankle Injuries”

March 3, 2018

abwExcellent article. Thank you.

July 30, 2018

Arun SayalThanks abw!

Happy to share these earls from our orthopedic surgeons – and from our patients.

Thanks to both groups for teaching me!

Arun