Headache is a very common chief complaint in emergency department (ED) presentations. Of these patients, 98 percent will have a benign etiology. Of the remaining two percent, one percent will be reliably diagnosed on unenhanced CT or lumbar puncture (LP), however the other one percent cannot be ruled out on unenhanced CT or LP.1 One example of a potentially life-threatening condition that most often presents with headache and cannot be ruled out with unenhanced CT and LP is cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Unenhanced CT has only a 41 percent to 73 percent sensitivity for the diagnosis of CVT, with CT venogram being the diagnostic test of choice in the ED, and MRI venogram being the gold standard.2 This is just one reason the diagnosis is difficult to make in the ED. Another reason is that clinical manifestations are highly variable and nonspecific, as there are a multitude of possible locations of thrombosis that do not follow a typical arterial ischemic stroke distribution, and evolution over time is variable. The median time to diagnosis between initial presentation and diagnosis is seven days, however, CVT can present like a subarachnoid hemorrhage with a “thunderclap” headache, or gradually over days to weeks.3 In fact, the headache of CVT has no specific characteristics, most often being diffuse, progressive, and severe, but sometimes unilateral, sudden, or mild, and sometimes migraine-like. Pain can originate from tension on the vein itself or from raised intracerebral pressure which causes diffuse headache. It may be positional (worse in the supine position) and may be aggravated by Valsalva, reflecting raised intracerebral pressure. Features that make the diagnosis of CVT less likely include purely unilateral pain, scintillating scotoma, and recurrent or episodic headache. Return visits to the ED for the same headache should be considered a risk factor. While headache is the most common chief complaint, others include seizure, encephalopathy, and focal neurologic symptoms.4

Explore This Issue

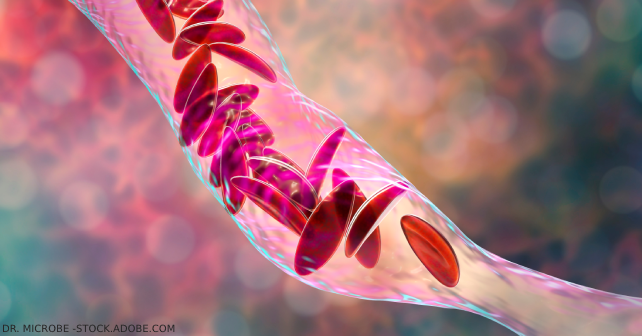

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 09 – September 2023An understanding of the pathophysiology helps to explain the myriad clinical possibilities. When a venous clot forms, venous and cerebrospinal fluid drainage suffer, leading to upstream increased pressures. Raised intracranial pressure, cerebral edema, hydrocephalus and decreased cerebral perfusion pressure may lead to brain ischemia and subsequent hemorrhagic transformation, which are often devastating. With this pathophysiology in mind, it is no surprise that CVT can present with various clinical findings including vision changes, diplopia, nausea and vomiting, papilledema, cranial nerve deficits, encephalopathy, neck pain, proptosis, chemosis, mastoid pain, hemiparesis, dysarthria, aphasia, seizures, bilateral motor deficits and pulsatile tinnitus.5 Nonetheless, CVT can be divided into four recognized syndromes, from most common to rarest: isolated elevated intracranial hypertension, focal neurologic syndrome, diffuse encephalopathy, and cavernous sinus syndrome, which may help the clinician in assessing pretest probability.

CVT is found most often in female patients 20 to 50 years of age.6 Risk factors include all the traditional thromboembolic risk factors including pregnancy, estrogen use, cancer, prolonged immobilization, etc., plus head and neck infections (leading to septic cavernous sinus thrombosis) and head trauma, including basal skull fracture.6

Two key clinical features of advanced CVT are papilledema and loss of venous pulsations on fundoscopy.7 POCUS may aid in identifying papilledema by measuring optic nerve sheath diameter, however the accuracy of this finding depends on the skill of the clinician.8

To curb the urge to order a CT venogram on every patient with unexplained headache, D-dimer has been proposed as a screening test for patients with a low pretest probability of CVT. The sensitivity of D-dimer for the diagnosis of CVT ranges from 82 percent to 98 percent, which is not good enough to rule out the diagnosis with certainty but may shift one’s pre-test probability to aid in decision making around imaging.9,10 D-dimer should be reserved for low pretest probability patients and it should be recognized that utilization of D-dimer may increase CT venogram use.

Unenhanced CT may reveal a hyperdensity in the superior sagittal sinus (the “delta sign”) or straight sinus (the “dense cord sign”), but only in about 30 percent of cases. Hemorrhage, seen in about 30 percent of patients, is readily apparent on unenhanced CT. The findings of isolated bilateral frontal lobar or thalamic hemorrhages are another clue to the diagnosis of CVT on unenhanced CT.11

Once a diagnosis of CVT is made, it is imperative that these patients are started on either unfractionated or low-molecularweight heparin. A common pitfall is to withhold administration of heparin when CT reveals hemorrhage(s). Even though hemorrhage extension is found in 11 percent of patients with CVT, this does not seem to be related to anticoagulation.12 Intracranial hemorrhage is not a contraindication to heparin administration in patients with CVT.13

So when should we consider the diagnosis of CVT in patients presenting to the ED with headache? Otherwise unexplained headache in a young female with thromboembolic risk factors should prompt us to consider the diagnosis, perform a careful fundoscopic exam and consider a D-dimer in low-risk patients to help further risk-stratify patients. Patients with unexplained headache plus seizure, altered level of awareness, or focal neurologic sign(s) should also be considered for the diagnosis of CVT. Those patients with unremarkable unenhanced CT and LP findings, but with persistent unexplained headache and risk factors for CVT should, with shared decision making, be considered for a CT venogram done in the ED.

A special thanks to Drs Roy Basking and Amit Shah for their expert contributions to the EM Cases podcast that inspired this column.

Dr. Helman is an emergency physician at North York General Hospital in Toronto. He is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Division of Emergency Medicine, and the education innovation lead at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. He is the founder and host of Emergency Medicine Cases podcast and website.

Dr. Helman is an emergency physician at North York General Hospital in Toronto. He is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Division of Emergency Medicine, and the education innovation lead at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. He is the founder and host of Emergency Medicine Cases podcast and website.

References

- Cerbo R, Villani V, Bruti G, et al. Primary headache in emergency department: prevalence, clinical features and therapeutical approach. J Headache Pain. 2005;6(4):287-9.

- Bonatti M, Valletta R, Lombardo F, et al. Accuracy of unenhanced CT in the diagnosis of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Radiol Med. 2021;126(3):399-404.

- Ulivi L, Squitieri M, Cohen H, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a practical guide. Pract Neurol. 2020;20(5):356-367.

- Ferro JM, Aguiar de Sousa D. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19(10):74.

- Idiculla PS, Gurala D, Palanisamy M, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a comprehensive review. Eur Neurol. 2020;83(4):369-379.

- Dmytriw AA, Song JSA, Yu E, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: state of the art diagnosis and management. Neuroradiology. 2018;60(7):669-685

- Luo Y, Tian X, Wang X. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis: a review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:2.

- Ohle R, Mcisaac SM, Woo MY, et al. Sonography of the optic nerve sheath diameter for detection of raised intracranial pressure compared to computed tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(7):1285-94.

- Alons IM, Jellema K, Wermer MJ, et al. D-dimer for the exclusion of cerebral venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis of low risk patients with isolated headache. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:118.

- Dentali F, Squizzato A, Marchesi C, et al. D-dimer testing in the diagnosis of cerebral vein thrombosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of the literature. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(4):582-9.

- Ge S, Wen J, Kei PL. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a spectrum of imaging findings. Singapore Med J. 2021;62(12):630-635.

- Capecchi M, Abbattista M, Martinelli I. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(10):1918-1931.

- Ferro JM, Bousser MG, Canhão P, et al. European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis – endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(10):1203-1213.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Tips for Diagnosing Cerebral Venous Thrombosis in the Emergency Dept.”