Written from the perspective of an emergency physician who also runs a weekly minor fracture clinic, this column is intended to highlight a few key ED teaching points for commonly missed and commonly mismanaged ED orthopedic cases.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 09 – September 2018Most ED patients with a negative knee X-ray will have a soft tissue injury (STI). However, scattered among those STIs are many commonly missed diagnoses. There can be an operative STI (eg, a quadriceps or patellar tendon rupture), a septic knee, a limb-threatening spontaneously reduced knee dislocation (rarely), or an occult fracture. In this article, we focus on diagnostic strategies for occult fractures in the ED.

From a diagnostic point of view, we must appreciate that while X-rays are good tests, they are not perfect. It is well-recognized that 20 to 30 percent of scaphoid fractures are radiographically occult.1,2 For fractures around the knee, the sensitivity of knee X-rays is around 85 percent.3,4 Though not specifically studied, the sensitivity of plain radiographs for detecting fractures in ED patients with musculoskeletal injuries is estimated at 90 to 95 percent.

Here are four cases from our hospital. All four patients had an occult fracture.

Case 1

A 12-year-old boy fell on his shoulder. The physical exam showed a tender, swollen mid-clavicle. X-rays were negative, and he was diagnosed with a probable STI of the clavicle. Treatment: a sling and follow-up in the minor fracture clinic.

Case 2

A 13-year-old girl twisted her ankle. Her physical exam showed an antalgic gait and a sore and swollen ankle. X-rays were negative. She was diagnosed with a Salter-Harris I distal fibula versus ankle sprain. Treatment: a splint and follow-up in the minor fracture clinic.

Case 3

A 69-year-old woman fell on her outstretched hand. Her physical exam revealed a tender, swollen distal radius. X-rays were negative, and she was diagnosed with a probable STI wrist. Treatment: a splint and follow-up in the minor fracture clinic.

Case 4

Photos: Arun Sayal

A 72-year-old woman twisted her knee. Her physical exam revealed an antalgic gait and a tender, swollen knee. X-rays were negative, and she was diagnosed with a medial collateral ligament injury. Treatment: A splint and follow-up in the minor fracture clinic.

Fracture Risk

In the emergency department, X-rays are often used as diagnostic tools, but it’s better to think of X-rays as fracture management tools. In simple terms, a fracture can occur in one of two ways. Fractures can occur via abnormal force on normal bone. For example, a 25-year-old man falls off a roof and suffers a comminuted fracture of his distal radius.

Alternatively, fractures can occur via normal force on abnormal bone. For example, an 85-year-old man with osteoporosis falls from a standing height and suffers a comminuted fracture of his distal radius. Elderly patients commonly fracture their hip without falling—it can be secondary to a relatively minor rotational force applied to an osteoporotic long bone.

So for those with weaker bone (i.e., the elderly and young) we should have a heightened awareness for fracture—and therefore require greater skepticism for a normal X-ray.

Better detection of occult fractures starts with appreciating that, for some reason, many clinicians have a different (perhaps flawed) diagnostic approach to musculoskeletal patients. When a normal radiograph is available prior to exam, our index of suspicion declines, but it shouldn’t be zero. Don’t be biased by a normal radiograph. Shortchanging a patient’s history and physical exam opens the door to missing subtle presentations.

To diagnose a patient with a fracture, do your best to determine:

- The mechanism of injury, including both the magnitude and direction of force—these factors predict injury patterns.

- The events after the injury. Delayed pain is less likely to be a fracture.

- Age, previous injuries, past medical history, and medications. Younger patients have softer/weaker bone; older patients have osteoporosis; orthopedic implants give rise to subtle periprosthetic fractures; neuropathy diminishes pain; long-term steroids can cause osteoporosis, etc.

- Signs of fracture, such as swelling, focal tenderness, and decreased range of motion. We must use the physical exam to confirm what we suspect by history.

Once you have determined a differential diagnosis for a patient and your pretest probability for a fracture, then (and only then) should you consider an X-ray. In fact, if the likelihood of an abnormal X-ray is low, then consider not ordering the test. And if your pretest probability is high, don’t dismiss a diagnosis of fracture just because the X-ray is normal.

As diagnosticians, we routinely apply Bayes’ theorem. We determine a pretest probability based on the history and physical exam. Then we order and interpret the test. With the result(s), we now determine our posttest probability.

Likelihood ratios (LRs) help us understand the value of a diagnostic test.5 An LR of 1 adds nothing to our diagnostic impression. But a high or low LR can make a diagnosis more or less probable, respectively.

The literature is not clear on a target LR for emergency department patients with a musculoskeletal injury and a negative X-ray, but a reasonable estimate is 0.05–0.1. For such patients, there is about a 90 to 95 percent chance they do not have a fracture versus a 5 to 10 percent chance they do have a fracture. So for the following examples, let’s split the difference and use an LR of 7.5 percent (ie, 0.075).

Example Patients

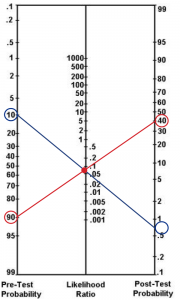

(click for larger image) Figure 1: A Fagan nomogram can be used to chart the chance that a patient with a negative X-ray has a fracture. Using a likelihood ratio of 0.075 (center line), the 10 percent pretest probability (left line) of Patient A (blue line) indicates a less than 1 percent post-test probability (right line). The 90 percent pretest probability (left line) of Patient B (red line) indicates a 40 percent post-test probability (right line).

Imagine that on your next shift, you see two patients with hip pain and normal X-rays. Patient A is a 25-year-old male who fell down two stairs onto his right hip. He has a limp and lateral hip tenderness, but he has a good range of motion (neither shortened or externally rotated). His estimated pretest probability for a fracture is 10 percent.

Patient B is a 78-year-old male who fell on his right hip from standing. He can’t walk due to the pain, is tender to palpation laterally at the hip, and has quite reduced active and passive range of motion of the hip due to pain (neither shortened or externally rotated). His estimated pretest probability for a fracture is 90 percent.

Again, both have normal X-rays of the hip and pelvis.

You mark Patient A’s 10 percent pretest probability of a fracture on a Fagan nomogram on the left axis, then draw a line from that mark through the estimated LR of 0.075 on the center axis and see where it intersects on post-test probability (ie, the right axis). See the blue line on Figure 1. Given the negative X-ray, you see the post-test probability of fracture is now less than 1 percent.

You do the same for Patient B, and despite his pretest probability of 90 percent for a fracture, you see the negative X-ray has driven the post-test probability of fracture down to around 40 percent. See the red line on Figure 1.

Negative X-rays in the face of a low pretest probability are unlikely to have a fracture, of course. However, we should keep the possibility of a fracture higher on the differential diagnosis for patients with a higher pretest probability for fracture and negative X-rays.

Remember this axiom: The purpose of any test is not to make the diagnosis but rather to affect our pre-test probability.

Case Resolutions

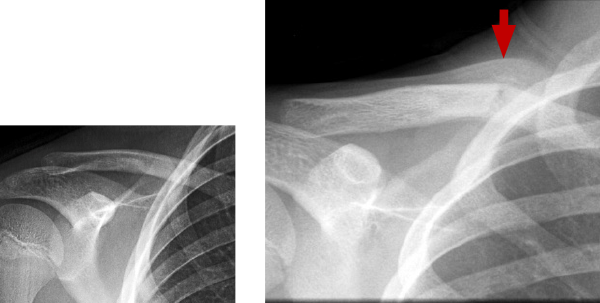

Case 1: occult mid-shaft clavicle fracture

The 12-year-old boy who fell on his shoulder: When he returned one week later he was still tender and swollen and looked like he had a clavicle fracture. He was kept in a sling, and X-rays repeated three weeks later revealed the fracture.

Left: Day 1 – normal

Right: Week 3 – fracture and callus

Case 2: occult distal tibia fracture

The 13-year-old girl with a twisted ankle: When she returned one week later, her mechanism was external rotation (a red flag, see image), and she was tender over her distal tibia. X-rays taken three weeks later showed an occult distal tibia fracture.

Left: Day 1 – normal

Right: Week 3 – subtle periosteal reaction lateral aspect distal tibia

Case 3: occult distal radius fracture

The 69-year-old woman who fell on her outstretched hand: When she returned one week later, she was still tender and swollen and looked like she had a distal radius fracture. She was kept in a splint, and X-rays repeated at four weeks revealed the fracture.

Left: Day 1 – normal

Right: Week 4 – sclerosis across distal radius

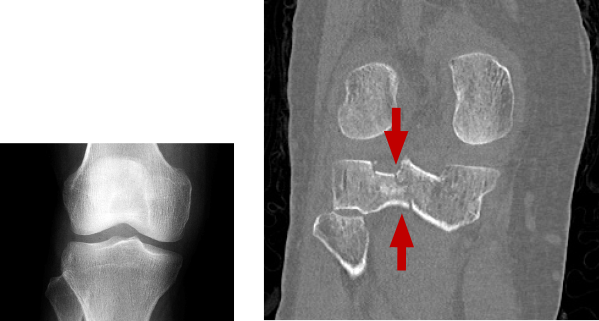

Case 4: occult lateral tibial plateau fracture

The 72-year-old woman who twisted her knee: When she returned one week later, she was still unable to bear weight on the knee, and she was swollen and tender over the lateral joint line. Follow-up imaging revealed a lateral tibial plateau fracture.

Left: Day 1 – normal

Right: Week 4 – sclerosis across distal radius

Our next column will deal with management strategies for suspected occult fractures in the emergency department.

Dr. Sayal is a staff physician in the emergency department and fracture clinic at North York General Hospital in Toronto, Ontario; creator and director of CASTED ‘Hands-On’ Orthopedic Courses; and associate professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Sayal is a staff physician in the emergency department and fracture clinic at North York General Hospital in Toronto, Ontario; creator and director of CASTED ‘Hands-On’ Orthopedic Courses; and associate professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto.

References

- Wheeless CR. Scaphoid frx: non diagnositic X-ray. Wheeless’ Textbook of Orthopaedics website. Accessed Aug. 17, 2017.

- Mallee WH, Wang J, Poolman RW, et al. Computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging versus bone scintigraphy for clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in patients with negative plain radiographs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD010023.

- Lin M. Beware the hidden tibia plateau fracture. Academic Life in Emergency Medicine website. Accessed Aug. 17, 2017.

- Mustonen AO, Koskinen SK, Kiuru MJ. Acute knee trauma: Analysis of multidetector computed tomography findings and comparison with conventional radiography. Acta Radiol. 2005;46(8):866-874.

- Likelihood ratios. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine website. Accessed Aug. 17, 2017.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Tips for Diagnosing Occult Fractures in the Emergency Department”