Although most seizures resolve spontaneously in one to three minutes, the seizures we typically face in the emergency department are the generalized tonic-clonic type and have been going on for a longer period of time, usually fulfilling the Neurocritical Care Society guidelines’ criteria for status epilepticus—a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes, or two or more seizures within a five-minute period without return to neurological baseline in between.1 We know status epilepticus is associated with a mortality rate as high as 43 percent, and as the duration of seizures increase, the outcomes become poorer, especially in seizures lasting more than 30 minutes, owing to brain anoxia, acidosis, and rhabdomyolysis that occurs with ongoing seizure activity.2,3 In fact, the seizure duration is the only potentially modifiable determinant of mortality. It is believed that the longer the seizure, the more refractory to medication it becomes.4

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 07 – July 2020The point: We should approach seizing patients in the emergency department swiftly and aggressively, with the goal of immediate seizure cessation.

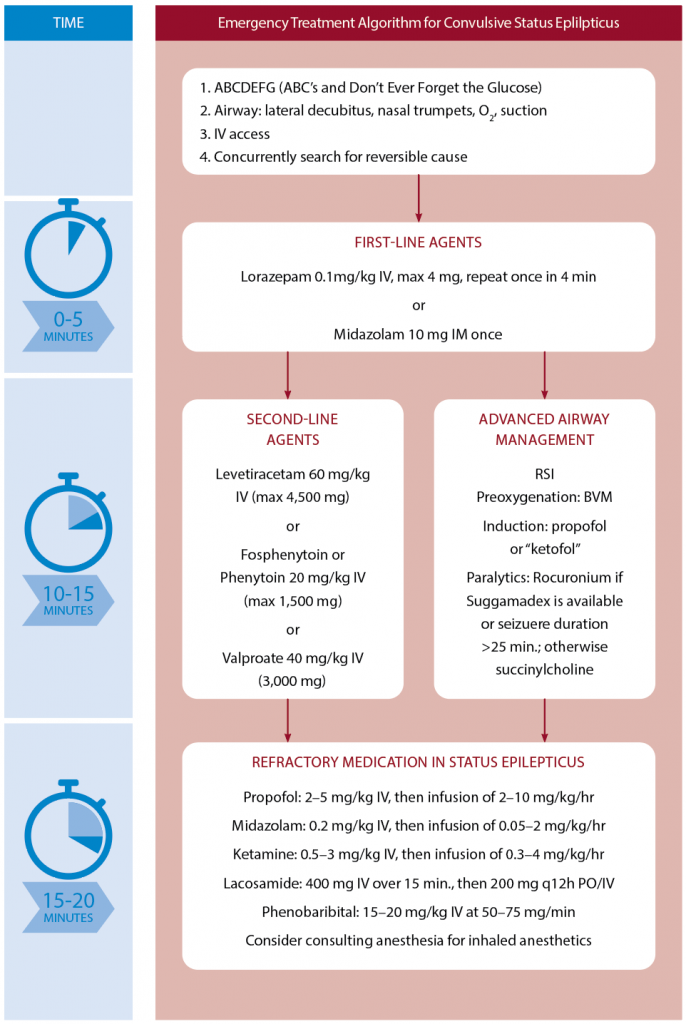

First-Line Agents

While the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with an IV established (with venous blood gas sent off to rule out hyponatremia as a cause of the seizure), capillary glucose checked, and oxygen delivered via nonrebreather and nasal trumpets, the first two doses of medication should be drawn up so they can be given in rapid succession if needed. Benzodiazepines are considered the first-line medication for seizures.1 The most important determinant of benzodiazepine efficacy in terminating seizures may be time to administration rather than choice of benzodiazepine or route.

The goal: to administer the first dose as soon as possible. Although some experts recommend waiting five minutes before administering the first benzodiazepine dose and giving it slowly over a few minutes (the reasoning being that the majority of seizures resolve spontaneously in less than five minutes and that these medications at therapeutic doses produce significant side effects), apnea and hypotension are more common with ongoing seizure activity. Aborting the seizure results in less respiratory depression, despite the high benzodiazepine dose. As such, I recommend administering the first benzodiazepine as soon as possible, via intravenous (IV) push.

The next most important aspect of benzodiazepine administration in patients suffering from status epilepticus concerns adequate dosing. Don’t just give 2 mg of lorazepam. Why? Observational studies suggest benzodiazepines are underdosed in 76 percent of status epilepticus patients.5 It is imperative the first dose of benzodiazepine is dosed properly (ie, lorazepam 0.1 mg/kg IV up to 4 mg or midazolam 0.2 mg/kg intramuscular [IM] up to 10 mg). IV lorazepam is the preferred benzodiazepine because it has been shown to be better than diazepam for time to cessation of seizures and requirement of a different drug or general anesthesia.1,6,7 When no IV is available, IM midazolam is preferred because it has been shown to be noninferior to IV lorazepam in a recent landmark randomized controlled trial.8

Again, treat seizures early via IV push with adequate doses of benzodiazepines.

Anton Helman

Second-Line Agents

After two adequate doses of IV lorazepam have been given two to four minutes apart, the drug you should reach for may surprise you. It’s propofol. Propofol should be considered concurrently with a traditional second-line agent such as levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, or valproic acid.9 It is important to understand that the goal of using propofol is to achieve seizure cessation, while the goal of traditional antiepileptic medications is to prevent seizure recurrence. Multiple trials have demonstrated unacceptable seizure durations of 30–45 minutes using traditional second-line agents without use of a sedative-hypnotic drug.10,11 Propofol use is familiar to emergency clinicians in other conditions and has been shown in recent meta-analysis to have a better disease control rate and faster results and reduced tracheal intubation time compared to barbiturates.12 The recommended dose is propofol IV bolus 2 mg/kg, followed by 50–80 mcg/kg/min (3–5 mg/kg/hr) infusion.

We should approach seizing patients in the emergency department swiftly and aggressively, with the goal of immediate seizure cessation.

Turning to intubation, some experts recommend ketofol (ketamine plus propofol) based on the theoretical benefit of blocking both N-methyl-D-aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors with ketamine and propofol, respectively.13 I also recommend using a paralytic agent to maximize the chance of first-pass success. Long-term neuromuscular blockade should be avoided whenever possible so patients can be monitored for ongoing seizure activity and serial neurological exams can be conducted until EEG monitoring is available.

The choice of paralytic agent depends on patient factors, duration of seizure activity, and access to the rocuronium reversal agent sugammadex. If there are no clear contraindications for using succinylcholine and the patient has been seizing for less than 20–25 min, it is reasonable to use succinylcholine given its short duration of action. If sugammadex is available, consider rocuronium. Sugammadex should only be used in a controlled fashion to reverse the rocuronium after the airway has been secured and the patient has been stabilized. Its purpose in status epilepticus is only to reveal underlying physical seizure activity to aid in titrating sedative infusions rather than as a tool used for an anticipated difficult/challenging airway.

Choosing among antiepileptic drugs is less about any upsides and more about avoiding contraindications. The recent ESETT trial, which included adults and children with persistent benzodiazepine refractory generalized convulsive status epilepticus, found no difference between the use of levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate in seizure cessation and improved alertness by 60 minutes.14 However, phenytoin and fosphenytoin have sodium channel blockade effects, similar to the mechanism of action of certain toxidromes such as tricyclic antidepressant and cocaine overdose. The additional sodium channel blockade of phenytoin/fosphenytoin could therefore result in dangerous and even fatal cardiac dysrhythmias. These drugs should generally be avoided in toxicological causes of seizure for this reason. Although controversial, valproate should be avoided in pregnant patients.15 Perhaps the safest medication is levetiracetam dosed at 60 mg/kg IV (maximum 4.5 g).

Third-Line Agents

For refractory status epilepticus, defined by failure of seizure cessation after a second-line medication, options include propofol, midazolam (0.2 mg/kg IV, then infusion of 0.05–2 mg/kg/hr), ketamine (0.5–3 mg/kg IV, then infusion of 0.3–4 mg/kg/hr), lacosamide (400 mg IV over 15 minutes, then maintenance of 200 mg q12h PO/IV), and phenobarbital (15–20 mg/kg IV at 50–75 mg/min) in consultation with an intensivist.

Underlying Cause

A concurrent search for the underlying cause of the seizure should be pursued. Always start by considering any immediate life-threatening conditions that require immediate treatment with specific antidotes (in parentheses below). These include:

- Vital sign extremes: hypoxemia (oxygen), hypertensive encephalopathy (labetalol, etc.), and severe hyperthermia (cooling)

- Metabolic: hypoglycemia (glucose), hyponatremia (hypertonic saline), hypomagnesemia (magnesium sulphate), and hypocalcemia (calcium gluconate or calcium chloride)

- Toxicologic: anticholinergics (bicarbonate), isoniazid (pyridoxine), lipophilic drug overdose (lipid emulsion), etc.

- Eclampsia: typically after 20 weeks of pregnancy and up to eight weeks postpartum (magnesium sulphate)

After such conditions have been identified/treated or excluded, it is useful to divide other possible causes into intracranial versus systemic. Imaging and lumbar punctures may be indicated.

With this approach, you can lower the risk of anoxic brain injury, multiorgan failure, and death as a result of refractory status epilepticus in your patients with status epilepticus.

And if you can’t remember all the details and remember only one thing in the heat of the moment, remember this: Go big, go early.

References

- Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):3-23.

- Logroscino G, Hesdorffer DC, Cascino GD, et al. Long-term mortality after a first episode of status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58(4):537-541.

- Boggs JG. Mortality associated with status epilepticus. Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4(1):25-27.

- Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et. al. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children and adults: report of the guideline committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16(1):48-61.

- Kellinghaus C, Rossetti AO, Trinka E, et al. Factors predicting cessation of status epilepticus in clinical practice: data from a prospective observational registry (SENSE). Ann Neurol. 2019;85(3):421-432.

- Prasad K, Krishnan PR, Al-Roomi K, et al. Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):640-647.

- Prasad M, Krishnan PR, Sequeira R, et al. Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(9):CD003723.

- Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):591-600.

- Morgenstern J. Status epilepticus: emergency management. First10EM website.

- Dalziel SR, Borland ML, Furyk J, et al. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children (ConSEPT): an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10186):2135-2145.

- Lyttle MD, Rainford NEA, Gamble C, et al. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of paediatric convulsive status epilepticus (EcLiPSE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10186):2125-2134.

- Zhang Q, Yu Y, Lu Y, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of propofol versus barbiturates for controlling refractory status epilepticus. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):55

- Farkas J. PulmCrit – Resuscitationist’s guide to status epilepticus. PulmCrit (EMCrit) website.

- Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, et al. Randomized trial of three anticonvulsant medications for status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2103-2113.

- Wieck A, Jones S. Dangers of valproate in pregnancy. BMJ. 2018;361:k1609.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Tips for Managing Active Seizures in the Emergency Department”