2. Break the Bad News

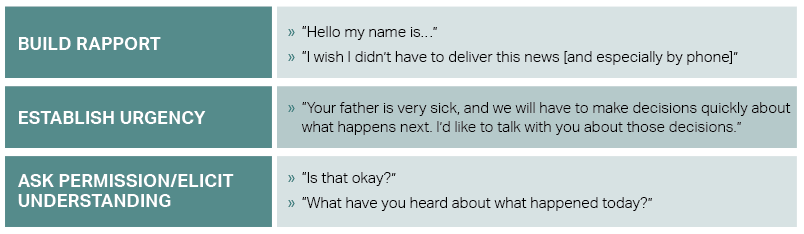

Obtaining permission prior to this step allows for the patient or family/friend to emotionally prepare and gives them a sense of control. After obtaining permission, deliver the headline using simple, straightforward lay terms. Often, this a time for the physician to recognize and respond to emotions as they arise.

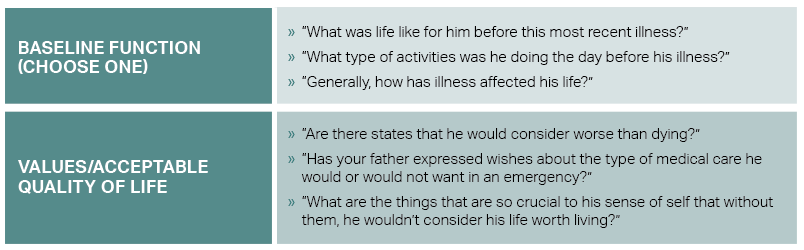

3. Learn Their Story

It is important to concisely learn the patient’s history and values related to an acceptable quality of life. The physician may first use an alignment statement to frame the conversation. An example of this may be, “For us to decide what’s best for your loved one, it’s important that I understand more about them—who they are and what matters most to them.” Included in this step is learning about the patient’s baseline quality of life, which will allow both for prognostication and recommendations.

Even as patients hope to avoid death and we as physicians attempt to prevent it, many patients identify scenarios that they deem worse than death. In a cohort study, more than 50 percent of those surveyed said that relying on a breathing machine to live is worse than death. Nearly half of respondents also stated that the inability to get out of bed is worse than death. Living in a nursing home was also worse than death for 30 percent of older adults.7 Unknown to most of the general population, one in three older adults who are intubated in the emergency department will not survive the hospitalization. Among those who do survive, nearly 80 percent will be discharged somewhere other than home, such as a long-term care facility or nursing home.1

4. Summarize and Recommend

After reviewing the patient’s values and acceptable quality of life, the emergency physician should summarize what they heard from the patient or surrogate before moving on to recommendations. It is critical that any recommendation aligns with the patient’s values and is not biased on the clinical presentation or assumptions made about the patient’s prior quality of life. The physician should reflect on whether the treatment course will realistically allow for the patient to return to the quality of life they experienced prior to this acute illness. Using the example related to endotracheal intubation:

Palliative care is best when it serves the patient throughout their life-limiting illness. However, many emergency physicians find themselves initiating core palliative concepts, such as goals-of-care conversations, to patients in extremis or their loved ones. In only a few minutes, using the steps and tools mentioned here, physicians can master the crucial procedure of rapid code status conversations and can deliver care that is aligned with the patient’s values and goals.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Tips for Mastering the Crucial Skill of Rapid Code Status Conversations”