As emergency physicians, we are trained in the core procedures surrounding critical illness and resuscitation, such as endotracheal intubations, central venous catheter placement and chest tube thoracostomies. However, a critical component of the initial resuscitation that is often not recognized as a critical procedure is the rapid code status conversation. Concepts surrounding goals of care, communication of challenging news, and recognition of palliative care basics are fundamental for modern emergency physicians to practice compassionately and effectively. More than 75 percent of Americans visit an emergency department within the last six months of life.1 As such, it is not surprising that the treatment decisions made in the emergency department affect the trajectories of care of these patients.1 To that end, understanding the nuances and specific skills needed to care for patients at the end of life is critical for emergency physicians. This includes ending resuscitation efforts if they are not aligned with the patient’s goals of care. In addition to this being a core component of high-quality patient-centered care, there recently have also been several “wrongful life” lawsuits in which doctors did not follow advance directives (MOLST or POLST forms) or the direction of health care proxies, further reinforcing the importance of this issue.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 04 – April 2022Goals of care is a term frequently used when referring to a patient’s intubation or code status; however, the term should instead be understood more broadly and relate to every facet of care that a patient receives. Unfortunately, many patients have never had a goals-of-care conversation prior to arrival in the emergency department. Some who have cannot recall it or arrive without documentation of it. Of course, the challenge of having these conversations in the emergency department is the time-pressured environment we work in, clinical instability of our patients, and our lack of longitudinal relationships.1,2

In addition to patient access to more “upstream” goals-of-care conversations in the outpatient setting,3 or with clinically stable patients in the emergency department leveraging the interdisciplinary team such as registered nurses or social workers, it remains critical that all emergency physicians are facile with the rapid code status conversation: a conversation that elicits the critical information we need to ensure goal-concordant care in a way that is amenable to our time-pressured environment.4,5 However, when surveyed, 80 percent of residents expressed a need for more training in palliative medicine.6 Much like any other procedure taught to us in training, we have outlined the key components of a rapid code status conversation, leveraging prior work, that should only take minutes to complete.1,2

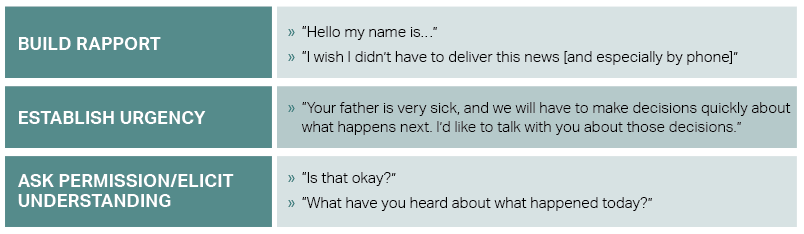

1. Establish Urgency and Elicit Understanding

Promptly establish rapport with the patient/surrogate by introducing yourself and the situation. Establish urgency regarding the patient’s clinical condition and ask permission to discuss next steps. Before moving on, establish what the patient/surrogate already knows regarding the patient’s condition, which will enable you to be more efficient and not repeat information that is already known.

2. Break the Bad News

Obtaining permission prior to this step allows for the patient or family/friend to emotionally prepare and gives them a sense of control. After obtaining permission, deliver the headline using simple, straightforward lay terms. Often, this a time for the physician to recognize and respond to emotions as they arise.

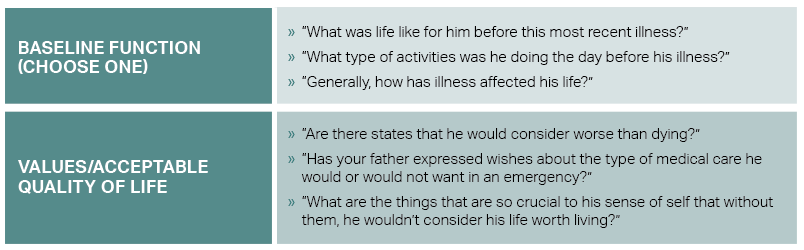

3. Learn Their Story

It is important to concisely learn the patient’s history and values related to an acceptable quality of life. The physician may first use an alignment statement to frame the conversation. An example of this may be, “For us to decide what’s best for your loved one, it’s important that I understand more about them—who they are and what matters most to them.” Included in this step is learning about the patient’s baseline quality of life, which will allow both for prognostication and recommendations.

Even as patients hope to avoid death and we as physicians attempt to prevent it, many patients identify scenarios that they deem worse than death. In a cohort study, more than 50 percent of those surveyed said that relying on a breathing machine to live is worse than death. Nearly half of respondents also stated that the inability to get out of bed is worse than death. Living in a nursing home was also worse than death for 30 percent of older adults.7 Unknown to most of the general population, one in three older adults who are intubated in the emergency department will not survive the hospitalization. Among those who do survive, nearly 80 percent will be discharged somewhere other than home, such as a long-term care facility or nursing home.1

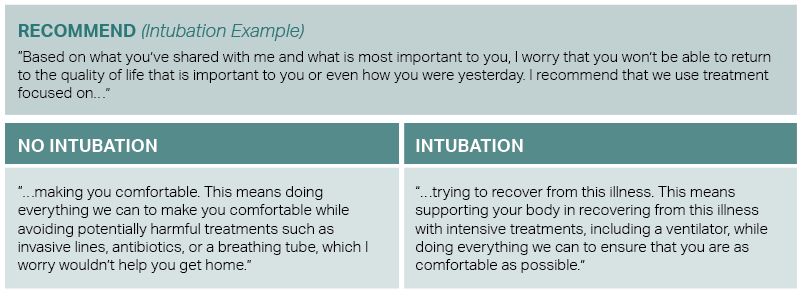

4. Summarize and Recommend

After reviewing the patient’s values and acceptable quality of life, the emergency physician should summarize what they heard from the patient or surrogate before moving on to recommendations. It is critical that any recommendation aligns with the patient’s values and is not biased on the clinical presentation or assumptions made about the patient’s prior quality of life. The physician should reflect on whether the treatment course will realistically allow for the patient to return to the quality of life they experienced prior to this acute illness. Using the example related to endotracheal intubation:

Palliative care is best when it serves the patient throughout their life-limiting illness. However, many emergency physicians find themselves initiating core palliative concepts, such as goals-of-care conversations, to patients in extremis or their loved ones. In only a few minutes, using the steps and tools mentioned here, physicians can master the crucial procedure of rapid code status conversations and can deliver care that is aligned with the patient’s values and goals.

DR. ZIRULNIK is a second-year resident in the Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency. DR. OUCHI is an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School. DR. WANG is a palliative medicine specialist at Scripps Health in San Diego, California. DR. AARONSON is the Associate Chief Quality Officer at Massachusetts General Hospital, and an Emergency Medicine physician.

References

- Ouchi K, Lawton AJ, Bowman J, et al. Managing code status conversations for seriously ill older adults in respiratory failure. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(6):751-756.

- Wang DH. Beyond code status: palliative care begins in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(4):437-443.

- Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):751-759.

- Ouchi K, George N, Revette AC, et al. Empower seriously ill older adults to formulate their goals for medical care in the emergency department. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(3):267-273.

- Aaronson EL, Greenwald JL, Krenzel LR, et al. Adapting the serious illness conversation guide for use in the emergency department by social workers. Palliat Support Care. 2021;1-5.

- Lamba S, Pound A, Rella JG, et al. Emergency medicine resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):516-520.

- Rubin EB, Buehler AE, Halpern SD. States worse than death among hospitalized patients with serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1557-1559.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Tips for Mastering the Crucial Skill of Rapid Code Status Conversations”