Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks are becoming an integral aspect of multimodal pain management in emergency departments. Ultrasound guidance allows clinicians to visualize both the target structures (nerve and surrounding fascial planes) and the advancing block needle. In our experience teaching ultrasound-guided nerve blocks over the past 15 years, clear needle tip visualization is often the most difficult “microskill” to master. A misplaced needle can result in inadvertent vascular puncture or direct nerve injury. Here, we outline some practical techniques that allow learners to better visualize the needle tip during nerve blocks and improve success rates. These skills can elevate ultrasound-guided nerve blocks to become an essential element of your multimodal pain management of the acutely injured patient.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 06 – June 2021Proper Equipment Setup

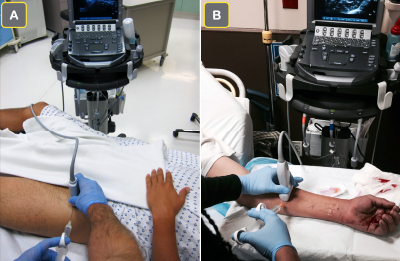

Ideal clinician and patient positioning improves success when performing any emergency department procedure. This holds true for ultrasound-guided nerve blocks. Unfortunately, patient positioning can be difficult in the acutely injured patient, adding another challenge. We recommend adhering to basic ergonomic principles to ensure that the view of the needle and ultrasound screen remain in the same line of sight when performing a block.1

Figure 1A: The ultrasound screen is placed contralateral to the injured extremity when performing a femoral nerve block. This allows the clinician to view the ultrasound screen and the site of needle entry in the same line of sight.

Figure 1B: For a forearm nerve block for a palmar laceration, the ultrasound screen is placed on the ipsilateral side of the injury to allow for a clear line of sight.

photos: Arun Nagdev

The ultrasound screen positioning will vary depending on the block performed, but the general principle of keeping the ultrasound screen in line of sight is one of the keys to success. For example, when performing an ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block, we recommend placing the ultrasound screen contralateral to the site of injury (see Figure 1A). Conversely, for a patient with a palmar laceration (requiring a forearm nerve block), the clinician can place the ultrasound system on the same side as the injury to maintain clear line of sight (see Figure 1B). The clinician should determine the ideal position of both the patient and the ultrasound screen while setting up for the block. The extra few minutes spent up front determining the ideal ergonomic positioning will increase block success and often end up saving time overall.

Optimal Hand and Transducer Positioning

Optimal hand stability during ultrasound-guided nerve blocks can be accomplished with a few simple techniques. The operator should hold the ultrasound transducer with their nondominant hand and rest the medial aspect of their palm to stabilize the probe (termed “anchoring”) (see Figure 2A). The operator can also use their fourth or fifth finger to further stabilize the probe against the patient.

Figure 2A: For a distal sciatic nerve block in the popliteal fossa, the clinician has stabilized their nondominant hand during the block.

Figure 2B: Once the needle has entered the soft tissue, gentle probe manipulation (fananing or rotating) can allow for proper needle visualization.

After skin puncture, alternating subtle transducer movements with gentle needle manipulation will allow the needle tip to come into view. If the needle is not already in view, close attention to tissue deformation with needle movement will give clues as to its location. If needle sight is lost, take a moment to look away from the display screen to visually inspect the transducer position on the skin and its relationship to the needle’s path. The transducer can then be fanned or rotated to visualize the needle clearly (see Figure 2B).1

Optimizing Needle Visualization by “Toeing In” the Transducer

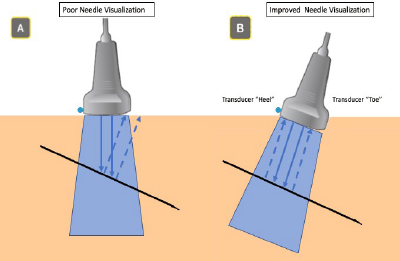

Needle visualization during in-plane ultrasound-guided nerve blocks with a steep needle trajectory is particularly challenging. Adjusting the “angle of insonation” can produce a crisp, clear image of the needle as it travels toward its intended target.

The angle of insonation refers to the angle at which an ultrasound beam intersects the nerve block needle. The smooth, metallic surface of the needle effectively functions as a mirror for ultrasound waves, thus small changes to the angle of the needle greatly influence its visualization (see Figure 3).2 If the ultrasound beam is perpendicular to the needle (ie, angle of insonation of 90 degrees), the majority of ultrasound waves are reflected back toward the transducer, creating a bright, clear image of the needle (see Figures 3B and 4B).3 Unfortunately, deeper targets necessitate a steeper needle trajectory and therefore create a lower angle of insonation. The result is that the majority of ultrasound waves are reflected away from the transducer and the needle is poorly visualized (see Figures 3A and 4A).

Figure 3A: Low angle of insonation: some ultrasound waves are reflected away from the transducer.

Figure 3B: High angle of insonation: a majority of ultrasound waves are reflected toward the transducer.

To effectively raise the angle of insonation (and thereby optimize needle visualization), an operator may rock or “toe in” the ultrasound transducer (see Figure 5).3 This is best achieved by pressing one end (the “toe”) of the transducer deeper into the superficial soft tissue so that the trajectory of the transducer more closely mimics the trajectory of the needle (see Figure 5B). A generous allocation of ultrasound gel can help ensure the other end of the transducer (the “heel”) maintains contact with the skin surface. For very deep targets, switching from a linear to a curvilinear transducer will facilitate more exaggerated toeing/rocking and improved deep structure resolution. Also, many commercial nerve block needles have etched patterns which serve to make the needle tip more echogenic. Use of such needles can further enhance needle visualization, particularly for nerve blocks necessitating a steep angle of approach.2,3

Figure 4A: Poorly visualized needle due to low angle of insonation.

Figure 4B: Improved needle visualization after “toeing in” transducer.

Optimizing Needle Visualization by Hydrolocation and Hydrodissection

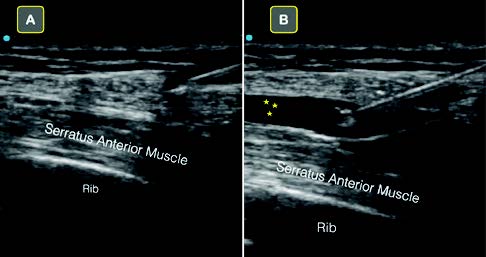

Hydrolocation and hydrodissection are additional techniques that help localize the needle tip during an in-plane ultrasound-guided nerve block.

Hydrolocation refers to a gentle yet rapid deposition of a small amount of normal saline to produce a small anechoic window, allowing better needle tip visualization. Hydrodissection uses this same fluid to dissect structures, classically fascial planes, when performing nerve blocks, providing confirmation of the proper location and fluid anesthetic placement.

Figure 5A: Standard transducer positioning.

Figure 5B: Operator “toes in” transducer.

During hydrolocation, as the clinician approaches the ideal location for anesthetic deposition, small aliquots of normal saline (<0.5–1 mLs) are gently pushed (with the help of an assistant) to visualize the needle tip. If the sonographer is off-axis (ie, the transducer is not in-plane with the needle shaft and tip), the sonographer will not see anechoic fluid coming from the needle tip. The sonographer can adjust the needle or transducer, and the assistant can inject another small aliquot to confirm needle tip localization.

During hydrodissection, we recommend using the overlying fascial plane as an optimal landmark for needle tip placement and anesthetic deposition. Using aliquots of normal saline (2–5 mL), the goal is to clearly visualize the opening (expansion) of targeted fascial planes with anechoic fluid (see Figure 6). Only then should an assistant gently infuse the anesthetic. If the clinician does not produce a clear anechoic pocket separating the targeted fascial planes, they are not in the desired space. Once the fascial plane is clearly opened with anechoic normal saline, we recommend slowly and gently depositing anesthetic for optimal block success.2

Figure 6A: The clearly visualized needle tip is seen above the serratus anterior muscle.

Figure 6B: Note that normal saline is used to hydrodissect the fascial plane that lies just above the serratus anterior muscle. Once this anechoic space is clearly defined, anesthetic can be safely deposited.

Conclusion

Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks are becoming an important clinical skill for emergency physicians. They provide directed anesthetic deposition, reduce reliance on opioids, and can even replace procedural sedation in some cases.

In our experience teaching ultrasound-guided nerve blocks, locating the needle tip during in-plane blocks is often the most challenging aspect of a procedure. Optimizing ultrasound screen positioning, properly stabilizing the ultrasound transducer with the nondominant hand, “toeing in” the transducer for steep blocks, and using normal saline to both hydrolocate the needle tip as well as hydrodissect fascial planes improve success.

We hope these easily incorporated block “microskills” will improve your confidence when performing your next ultrasound-guided nerve block.

Dr. Schultz and Dr. Yang are EM fellows and Dr. Jefferson is an EM resident at Alameda Health System–Highland Hospital in Oakland, California.

Dr. Mantuani is ultrasound fellowship director at Highland Hospital. Dr. Nagdev is director of emergency ultrasound at Highland Hospital.

References

- Tirado A, Nagdev A, Henningsen C, et al. Ultrasound-guided procedures in the emergency department—needle guidance and localization. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2013;31(1):87-115.

- Chin KJ, Perlas A, Chan VWS, et al. Needle visualization in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia: challenges and solutions. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(6):532-544.

- Henderson M, Dolan J. Challenges, solutions, and advances in ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia. BJA Edu. 2016;16(11):374-380.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Tips for Performing Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blocks in the Emergency Department”