Hyperangulated video laryngoscopes have blade shapes with a curvature more acute than a standard Macintosh blade. Commercial products include the GlideScope, Storz D-Blade, and McGrath X blade. In the course of teaching use of these devices, I have often been told, “I had a great view but had trouble delivering the tube.”

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 12 – December 2015Hyperangulated blades look around the curvature of the tongue very well, but their perspective on the larynx, looking upward at it from the base of the tongue, can lead to difficulty in tube delivery. If the blade is inserted too deeply, the video-imaging element gets very close to the larynx, and the view will be great, but the angle of approach is consequently very extreme. This creates difficulty with tube delivery through three mechanisms. First, it steepens the up angle to the larynx; second, it shortens the tube delivery area (distance from blade tip to larynx); and third, it reduces the area on the screen for observing tube delivery. Operators must be careful that they look in the mouth when inserting a hyperangulated stylet, then carefully observe it coming into view on the monitor. Jamming a rigid hyperangulated stylet into the posterior pharynx (off screen) can cause injury to the soft palate, tonsils, or hypopharynx.

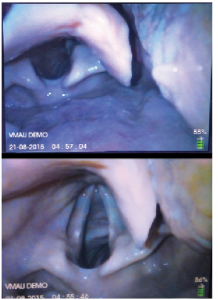

George Kovacs, MD, MHPE, an emergency physician from Halifax, Nova Scotia, and director of the Airway Interventions & Management in Emergencies (AIME) courses, recently showed me a simple way to determine if the angle of approach using a hyperangulated blade is excessive. I have labeled this “Kovacs’ sign” and now incorporate it into my instruction with hyperangulated blades (see Figures 1 and 2). If the blade is overinserted, the cricoid ring becomes visible between the vocal cords. This indicates a very steep angle of approach and will likely make tube introduction difficult. Conversely, when the angle of approach is not so steep, the cricoid ring is not seen, there is more room between the blade tip and the larynx, and there will be more space on the inferior aspect of the monitor to observe tube delivery.

Figure 1 (Left). Blade positioning and Kovacs’ sign. In the upper image (ideal placement), the cricoid ring is not seen. There is more room beneath the posterior larynx on the monitor screen, which is critical for observing tube delivery. In the lower image, the cricoid ring and the internal aspect of the criothyroid membrane are visible between the vocal cords, indicating over-insertion of the hyperangulated blade and a steep angle of approach.

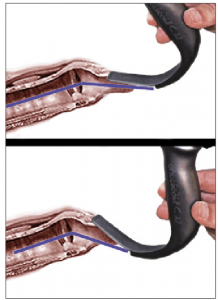

Figure 2 (Right). Schematic representation of the angle of approach. The top image shows ideal placement of a hyperangulated blade—in this case, a GlideScope Titanium blade—compared to overinsertion (bottom image). Note that the approach angle is more acute and that there is less room for tube delivery between the blade and the larynx.

The second piece of the puzzle with a hyperangulated video blade is getting the tube to drop into the trachea. One cannot merely advance the stylet, as the curvature used to get around the tongue creates a side-to-side dimension that exceeds the diameter of the human trachea. The trachea is only 15–20 mm in males and 14–16 mm in females. Additionally, if the hyperangulated stylet is simply rotated upward through the cords, the direction the tube and stylet points is upward, while the trachea has a downward inclination. Finally, there are the tracheal rings, which can prevent tube advancement when using a standard asymmetric left-beveled tracheal tube.

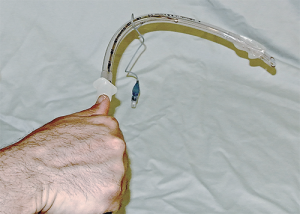

Verathon offers the GlideRite stylet to help with tube insertion. It is a rigid stylet with a 70-degree angle and a nifty proximal end, allowing the thumb to pop the stylet up (see Figure 3). A GlideRite stylet exceeds 2 inches in side-to-side dimension; this exceeds the dimensions of the human trachea. Accordingly, it is a tube delivery device (around the tongue and into the larynx), not a tracheal introducer. By partially removing the stylet after insertion through the cords, the tracheal tube can be advanced downward into the trachea. This maneuver, however, doesn’t address issues with the inclination of the trachea and the corrugation of the tracheal rings.

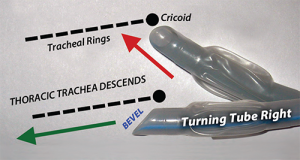

Figure 4. Right-turn overhand technique for hyperangulated stylet insertion into the trachea. By turning the stylet and tube 90 degrees, the tube angles downward, aligning with the inclination of the trachea. Note that the tube can be advanced in small increments off the stylet using the right hand only as long as an overhand grip is used at the top of the tube and stylet.

An easy maneuver, which can be done gradually by the operator with no assistance, is turning the GlideRite stylet and tube 90 degrees to the right after insertion through the cords (see Figures 4 and 5). The operator should use an overhand grip at the top of the stylet and tube. After insertion through the cords, the tube and stylet are turned rightward, to the corner of the patient’s mouth, while making sure the tip is through the larynx. The thumb is then used to slide the tube off the stylet in a series of gradual advancements. By turning the stylet and tube, the tube now points downward, overcoming the inclination problem. Turning 90 degrees also rotates the bevel of the tube upward, which prevents the tube tip from catching on the corrugation of the tracheal rings.

Try the overhand turn and make sure to watch for Kovacs’ sign on your next use of a hyperangulated video laryngoscope. These are simple tips that will improve your practice!

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “Tips for Using a Hyperangulated Video Laryngoscope”

January 10, 2016

Heston LaMar, MDThe proper use of the proximal end of the GlideRite stylet in terms of the “thumb pop” & also using it to steer the distal end of the tube is something that I think very few are taught or know (unless they have gone to a good recent airway course). Depth & angle are also key as you point out (which is why I hardly ever use a 4 blade on our GlideScope).

January 10, 2016

ML ClevelandCan you include a link to a video representation of using the overhand technique with the 90° rotation?