In the world of airway devices, there are few that have more fans than the beloved bougie. Although it has a British history—it was first described in 1949 by Sir Robert Macintosh, a New Zealander who moved to Britain—it seems wherever I travel people love their bougies. In many of the Commonwealth countries and throughout most of Europe, airway managers treat this device as mandatory for tube insertion. Enthusiasts promote it for direct and video laryngoscopy, the “bougie-aided cric,” and placement through supraglottic airways. Some folks believe it has magical magnetic properties that guide it exclusively into the trachea (not true).

Explore This Issue

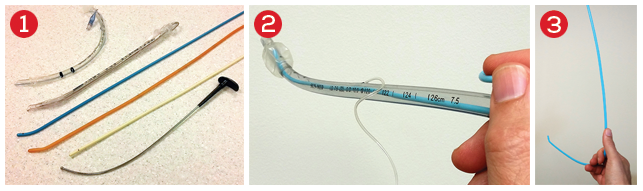

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 09 – September 2014During direct laryngoscopy, Sir Macintosh observed, “One of the difficulties in passing tubes beyond a certain size is that the body of the tube obscures the view of the cords through which the tip must be directed.” He described use of a “gum-elastic catheter,” which he passed through the cords first, followed by the tracheal tube. Although Sir Macintosh’s device was straight, he described shaping it into a curve to aid in cases of poor laryngeal exposure. Portex subsequently developed a tracheal tube introducer with a Coudé tip made of resin-covered fiberglass, but somehow the device has been labeled the “gum elastic bougie” despite that it is neither gum, elastic, nor a bougie (ie, a dilator). The Portex device can be reprocessed, but as the world of airway devices became disposable, a variety of companies introduced single-patient use plastic “bougies” with both straight and Coudé tip designs, such as one by SunMed USA in Grand Rapids, Michigan (see Figure 1). Not only are bougies available in different colors of plastic, there are different versions with special features, such as the Frova catheter by Cook Medical Critical Care in Bloomington, Indiana, and the Introes Pocket Bougie by BOMImed in Bensenville, Illinois. The Frova has a hollow lumen, allowing for oxygen insufflation; the Pocket bougie is made of Teflon and packaged in a rolled shape to fit into a pocket. Bougies are also available in a pediatric version, such as the 10 Fr compared to the 15 Fr diameter bougie from SunMed USA.

So what is magical about the bougie? Why the love affair? The bougie has three distinguishing characteristics that make it a useful adjunct for tube delivery. First, it has a smaller outer diameter than a tracheal tube. Most bougies are 5 mm (15 Fr); a tracheal tube of 7.5 mm inner diameter is almost twice as large in outer diameter as a bougie. Second, the upturned distal tip of the bougie, originally with a 38-degree bend angle, has an overall long axis dimension that does not exceed the dimensions of the trachea. The trachea is more narrow than most clinicians realize. In females, it is only 14–16 mm; in males, 15–20 mm. Because of the bougie’s flexibility and rounded distal tip, it usually passes into the trachea without hanging up on the tracheal rings. Finally, there is its tactile feel of the trachea on insertion. In 90 percent to 95 percent of cases, the bougie provides detection of the “rumble strip” of the anterior tracheal rings, assuming the tip is oriented anteriorly. The posterior membranous trachea is flat, so in order to appreciate the rings, the tip has to be properly oriented.

While the Europeans are steadfastly married to their bougies, Americans pioneered the use of stylets to aid in shaping and inserting tracheal tubes. Tracheal tubes have an inherent arcuate shape as a consequence of the way they are formed. This arcuate shape, with a wide side-to-side dimension, is not ideal for insertion into the narrowing confines of the upper airway, which Sir Macintosh appreciated. Minor rotation of the tube causes major lateral movement of the distal tip, and combined with blocking of the view, this a contributing factor in tube misplacement during direct laryngoscopy. A styletted tube, however, can be shaped into a long narrow axis shape, with a bend angle that respects the dimensions of the trachea (straight to cuff and 35 degrees, see Figure 2). When placed into this shape, I find that the distal tip of such a tube can be placed from below the line of sight, and tube insertion does not need to obscure the cords. I have carried a bougie in my airway tool kit for more than 15 years, and I have never deployed it in anger; I became obsessed with stylet shaping. A styletted tube can also be inserted faster (tube placed, stylet withdrawn) compared to a bougie intubation, which is generally a three-step process of bougie insertion, tube railroading, and bougie withdrawal.

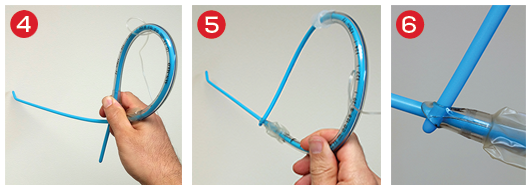

Despite my enthusiasm for a straight-to-cuff stylet, I think a bougie should be part of every airway kit. It can be useful in situations of poor laryngeal exposure, for placement into a trach, or in an emergent cric. The single-use versions are inexpensive. Some users complain it is hard to store because of its long length, about 60 cm. I address that issue by folding it in half. Bending the bougie and using a rubber band to keep it in this bent-over shape allows it to fit in intubation trays, draws, and jump bags. More important, when it is pulled out, this bent shape allows good control and preserves the long axis narrow dimension of the distal tip as it is inserted. Although the Pocket bougie is easy to carry, straightening may be needed depending on its intended use (especially for direct laryngoscopy).

Figure 1. Bougies and tube introducers: Tracheal tubes have an inherent arcuate shape (top). A malleable stylet can optimally shape a tube to be straight-to-cuff (35 degree bend, second from top). Bougies have long narrow axes with an upturned distal tip (Frova, blue color, allows for insufflation) and Smiths-Portex original design (resin covered fiberglass, beige). Cook Critical Care tracheal tube exchange catheter (straight shape, hollow bore for insufflation, second from bottom). The GlideRite stylet is used with a hyperangulated video blade to get the tube around the tongue, but has too wide a side-to-side dimension to insert into the trachea (bottom).

Figure 2. Straight-to-cuff styletted tube. Note the narrow long-axis view. There is a 35-degree bend at the proximal cuff. The stylet stops at the distal cuff, leaving the last few centimeters of the tube pliable.

Figure 3. The Shake grip: By folding the bougie in half and gripping the bougie this way, it is easy to determine the direction of the distal tip, prevent tube rotation, and achieve fine control of the device.

In an epiglottis-only view, always perform bimanual laryngoscopy (either with direct or video laryngoscopy) to try to visualize the interarytenoid notch, then direct the bougie tip over it to ensure you’re entering the trachea and not the esophagus. In the true epiglottis-only situation, make sure you keep the distal tip up (and feel the rings) as it can easily rotate under the epiglottis and miss the larynx.

The bougie has historically been held with a pencil grip. I find this not an easy way to keep it from rolling over; I want to track which way the distal tip is pointing. Some versions of the bougie place their depth markings (usually every 10 cm) on the same side as the direction of the Coudé tip, but this is not universal.

Figure 4. The Kiwi grip: A one-handed means of inserting the tube and bougie together, and prevent sliding of the devices on each other. After the bougie tip is inserted, the operator drops the laryngoscope and uses his or her left hand to counterclockwise rotate the tube down the bougie into the trachea.

Figure 5. The Kiwi-D grip, Jim Ducanto’s method of inserting the bougie tip into the Murphy eye of the tube as a one handed means of tube-bougie insertion.

Figure 6. Close up of the Kiwi-D grip showing tip of bougie in Murphy eye.

I think the best way to grip the bougie is what I call the “Shaka” grip (see Figure 3). “Shaka” is the Hawaiian hand gesture with the middle fingers folded over that means “hang loose.” Gripping the device this way, the user has fine control and knows the direction of the distal tip, and the insertion end is the proper length, all of which helps avoid rolling over.

If you work in a setting where you do not have anyone to help with tube placement over the bougie (while you keep the direct or video laryngoscope retracting the tongue), you can use a one-handed bougie/tube grip. I first found out about this from Paul Baker, senior lecturer in the department of anaesthesiology at The University of Auckland in New Zealand and director at Airway Simulation Limited, but I have been since informed he learned of it from an Italian physician. I named it the “Kiwi” grip a few years ago (see Figure 4). With this grip, you place the bougie/tube with your right hand, and after entering the trachea with the exposed distal tip of the device, you drop your laryngoscope, hold the top of the bougie with your left hand, and roll the tube down the bougie into the trachea with your right hand. Jim Ducanto, an anesthesiologist from Milwaukee who has an incredible passion for education and imaging, devised the Kiwi-D grip (tucking the tip of the bougie into the Murphy eye, see Figures 5 and 6).

Whatever grip you use when railroading tubes down a bougie, always do so with a left-handed turn of the tube as you pass the laryngeal inlet (approximately 14–16 cm from the mouth). This prevents any hang up on the laryngeal inlet (between the smaller outer diameter of the bougie and the larger inner diameter of the tube).

Make the bougie part of your airway kit. You’ll never know when it may come in handy.

Dr. Levitan is an adjunct professor of emergency medicine at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, N.H., and a visiting professor of emergency medicine at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. He works clinically at a critical care access hospital in rural New Hampshire and teaches cadaveric and fiber-optic airway courses.

Dr. Levitan is an adjunct professor of emergency medicine at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, N.H., and a visiting professor of emergency medicine at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. He works clinically at a critical care access hospital in rural New Hampshire and teaches cadaveric and fiber-optic airway courses.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “Tips for Handling the Bougie Airway Management Device”

September 25, 2014

visual aid: bougie handling tips | DAILYEM[…] in ACEP Now, with some handy tips for gripping the bougie so it feeds with the Coude tip up. Click through for the article, but if you have 30 seconds, check out the visual aids […]

February 22, 2024

Girijanandan D MenonUsed BIliary dilatation catheter used by endoscopist, as a substitute for bougie, to easily intubate a high anterior larynx in four cases.