What students raised in the millennial generation will bring to the health care workforce, and how medical school admissions, technical standards, and applicants have changed

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014Recently, I was sitting in our admissions committee meeting, getting ready to discuss the applicants we had interviewed. One of the other members chuckled and said, “Wouldn’t it be funny if we all brought our own medical school applications one day to review?” As we all laughed and looked around at one another (a bit uneasily, I might add), the only thing that kept going through my head was, “Awww, hell no.” (If you could, try to hear that with a little Alabama Southern drawl—it makes it sound much sweeter.)

I graduated from medical school in 1996, and things have drastically changed during the past 25 years. There are different standards and different expectations.

The Other Medical Reform

Abraham Flexner was an American educator who studied at Johns Hopkins University. He was invited by the Carnegie Foundation to review medical schools in the United States and Canada and to make recommendations for improvement. Interestingly, he evaluated these institutions from the viewpoint of an educator, not a medical practitioner. Based on his evaluations, the schools were placed in one of three categories:

- Those that compared favorably with Johns Hopkins (the gold standard)

- Those considered substandard but salvageable by providing financial assistance

- Those of such poor quality that they should be closed (sadly, the majority)1

And many schools were closed. Of the 133 MD-granting medical schools open and reviewed in 1910, only 85 remained in 1920.2 Some of the findings from Flexner’s study changed the landscape of medical education with drastic improvements. It was Flexner’s report that first suggested that clinical exposure was as vital to medical education as “a laboratory of chemistry or pathology,” encouraging hospitals both private and public to open their wards to teaching. This was with the caveat that the universities have sufficient funds to employ teachers who were dedicated to clinical science, highlighting the underlying deficiencies of medical schools to keep up with the increasing costs of quality medical education.3 This report was the beginning of the end of medical education as a for-profit enterprise.

Getting In

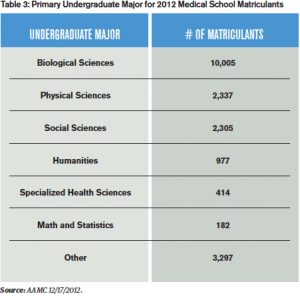

Fast forward 100 years. Gone are the days when two years of college (or less) could get you into medical school. Today, there are 129 fully accredited four-year U.S. medical schools, and in 2012 there were 45,266 applicants and 19,517 matriculants (46% of whom were female). Although admission requirements vary by institution, there are some universal standards. Most schools will have a minimum MCAT score and a certain number of undergraduate hours, including science, math, and English. GPAs are more flexible than MCAT scores, but special note is typically taken of the science GPA. Of note, the MCAT must be taken within three years of application, and there is a new MCAT that will launch in 2015 (after undergoing its fifth revision). Letters of recommendation are required, the most telling usually coming from the pre-health advisor at the undergraduate institution. Each institution has its own technical standards that need to be met, with reasonable accommodations, and include both physical and emotional components. And then there’s the other stuff.

Schools have struggled with the best way to interview medical student applicants, incorporating behavioral questions into the discussion to assess non-cognitive abilities. “Tell me about a time when you received some feedback that was difficult to hear.” These behavioral interviews are not the best way to identify students who may experience difficulties during medical school, particularly in the clinical years. Many schools have transitioned to Multiple Mini-Interviews (MMI). There are several stations (usually 10–12, each lasting 8–10 minutes). Domains assessed may include critical thinking, ethical decision-making, communication skills, and knowledge of the health care system, interspersed with more traditional interview questions.4 Studies have shown that the MMI is the most consistent predictor of success in the early years of medical school, as well as national licensing exams.5-6

References

- https://www.aamc.org/students/aspiring/

- 2003 Matriculating Student Questionnaire AAMC. 2003.

- 2013 Matriculating Student Questionnaire. AAMC December 2013.

- AAMC: Applicant Matriculant File as of 11/9/2011.

Reference

And then there’s the “other stuff.” This has become an important part of application preparation, with the hopes that it gives a glimpse into the patient-doctor relationship. Leadership and extracurricular activities are important markers of a well-rounded student who will be up to the new challenges that medical school will present. Research experience is nice, at least a taste (although many of the students I interview have projects that result in presentations and publications). And then there are the service and volunteer experiences: Habitat for Humanity, volunteering at free local health clinics or shelters, mission trips, working with children or the elderly in the community. On a fairly regular basis, there is a student with absolutely remarkable achievements in this aspect. For example, I’ve interviewed students who have established orphanages abroad. I am humbled on a regular basis.

Schools have struggled with the best way to interview medical student applicants, incorporating behavioral questions into the discussion to assess non-cognitive abilities. These behavioral interviews are not the best way to identify students who may experience difficulties during medical school.

Times—and People—Have Changed

I am a Generation X-er who was raised by Traditionalists, with Baby Boomers as older siblings, trying to counsel and advise Millennials. It sounds complex, so let’s break it down with reference to the current physician workforce.

Many of the Traditionalists have retired clinically but, not surprisingly, are still around to teach and pass on their wisdom: the classic Professor Emeritus. They value loyalty, hard work, and formality, and aren’t known for challenging the system. They believe in delayed gratification and seniority. These were the people for whom the term “resident” was coined because they lived at the hospital. They paved the way for the largest of the recognized generations, the Baby Boomers.

The Baby Boomers make up about 55 percent of the current physician workforce and hold most positions of authority. They associate hard work with self-worth, typically arriving early and leaving late. They are known for being competitive, and their personal lives often are casualties of professional success.7

Enter the Generation X-ers. Raised by Baby Boomers, they were characterized as “latch-key kids” and, possibly as a result, are more equally focused on their personal and professional lives. Their loyalty lies with themselves and with their families rather than with the institution. They are associated with the technological advances that developed at the same time. They are more likely to question authority and feel that evaluations should reflect accomplishments rather than time put in. They currently represent about 30 percent of the physician workforce.7

The majority of current residents and students (and about 5 percent of the practicing physician population) are Millennials. There has been a lot of attention given to Millennials entering the workforce and the differences they bring to the table. They are characterized as the first native online population, widely connected, with a penchant for advocacy for the underserved. Growing up, they were included by their parents on many family decisions, so they are not afraid to express their opinions but may be less independent, requiring more structured learning styles. They expect schedule flexibility to maintain work-life balance but feel a connection with their work colleagues as well.7 And, at least in my limited experience at one medical school, more of these students are choosing emergency medicine than ever before. This year, emergency medicine was the third-most sought out residency spot at the University of Alabama School of Medicine, behind only internal medicine and pediatrics.

Millennials bring a lot to the workforce. They have high expectations of themselves and of their coworkers and employers. They like to multitask and rely more heavily on technology. In terms of motivations, they tend to weigh achievement and affiliation more than power.8 From an emergency medicine standpoint, that sounds like a win-win! But potential conflicts can arise as well. A Millennial employee questioning a Baby Boomer boss (because that’s what they were taught to do) can lead to a tense workplace. The “everyone wins” mentality comes up against the “second place is first loser” attitude, with a few “live to work” people thrown in.

When I look at my own division, I see a little of each generation, and although this will continue to evolve, there are still issues that face all of us as we try to maneuver being a successful physician in 2014. It also gives us a glimpse into what the future holds.

The majority of current residents and students (and about 5% of the practicing physician population) are Millennials.

By 2025, Millennials will comprise almost 75 percent of the workforce. As that transition occurs, I would like to offer some insight into what makes them tick and what will drive their performance:

- Give feedback and plenty of it. However, remember that many of these people grew up surrounded by people telling them they could be whatever they wanted, and everyone got a trophy for participating. You might have to ease them into some of the constructive portions, but when they are given that, they respond very well.

- Be ready to negotiate. That’s what Millennials have been taught to do.

- Allow work in teams with many small deadlines. Long-term time management may be an issue.

- Don’t assume they are technologically savvy, but even if they aren’t, they are quick to master new things (unlike me and our ultrasound machine).

- Be able to enforce the “work to live” attitude. Life outside the department is crucial to longevity in this profession, although this is something I think we all need to learn to take advantage of.9

Dr. Sorrentino is associate professor of pediatric emergency medicine in the division of emergency medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, assistant dean for Students at the University of Alabama School of Medicine, and on the Board of Directors of Alabama ACEP.

Dr. Sorrentino is associate professor of pediatric emergency medicine in the division of emergency medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, assistant dean for Students at the University of Alabama School of Medicine, and on the Board of Directors of Alabama ACEP.

References

- Duffy TP. The Flexner Report–100 Years Later. Yale J Biol Med. 2011;84:269-276.

- Barzansky B. Abraham Flexner and the Era of Medical Education Reform. Acad Med. 2010;85:S19-S25.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. Bulletin Number Four. 1910. Available at: http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/sites/default/files/elibrary/Carnegie_Flexner_Report.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2013.

- Eva KW, Rosenfeld J, Reiter HI, et al. An Admissions OSCE: The Multiple Mini-Interview. Med Educ. 2004;38:314-326.

- Husbands A, Dowell J. Predictive Validity of the Dundee Multiple Mini-Interview. Med Educ. 2013;47:717-725.

- Eva KW, Reiter HI, Rosenfeld J, et al. Association Between a Medical School Admission Process Using the Multiple Mini-Interview and National Licensing Examination Scores. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2233-2240.

- Mohr NM, Moreno-Walton L, Mills AM, et al. Generational Influences in Academic Emergency Medicine: Teaching and Learning, Mentoring, and Technology (Part 1). Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(2):190-199.

- Borges NJ, Manuel RS, Elam CL, et al. Differences in Motives Between Millennial and Generation X Medical Students. Med Educ. 2010;44:570-576.

- 15 Tips for Motivating Gen Y in the Workplace. Available at: http://www.annaivey.com. Accessed Jan. 10, 2014.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Today’s Medical Students and the Medical School Landscape”